“Un festival de cinéma pour tous”, “A film festival for all’, is the slogan of the Festival Lumière, inaugurated in October 2009 in the city of Lyon, in South-East France. Known as the birthplace of cinema, Lyon is the city from which the Lumière brothers, the inventors of the Cinematograph, originally came. When thinking of a film festival, “its meaning is inseparable from its particular location” (Harbord 40). Being the second largest city in France, Lyon thereby creates a unique festival tone. Indeed, the strong influence of the Lumière Brothers’ achievements is still felt today, further glorifying the origins of the seventh art and strengthening its core values.

When it launched, the festival sold over 50,000 tickets within six days and achieved full capacity for almost all of its screenings. Since 2009 attendance has increased, with 150,000 people viewing 371 screenings across 60 venues in 2016. In 2010 the festival’s length was extended from five to seven days, and it is now considered an important international heritage film festival. This pattern coincides with Marijke Valck and Skadi Loist’s claim that “while cinema attendance is often bemoaned as declining, festival attendances across-the-board are reported as going up”(185). Festivals do create a sense of belonging to a group sharing a similar interest. In this case, the festivalgoers share a passion for cinema.

When it launched, the festival sold over 50,000 tickets within six days and achieved full capacity for almost all of its screenings. Since 2009 attendance has increased, with 150,000 people viewing 371 screenings across 60 venues in 2016. In 2010 the festival’s length was extended from five to seven days, and it is now considered an important international heritage film festival. This pattern coincides with Marijke Valck and Skadi Loist’s claim that “while cinema attendance is often bemoaned as declining, festival attendances across-the-board are reported as going up”(185). Festivals do create a sense of belonging to a group sharing a similar interest. In this case, the festivalgoers share a passion for cinema.

Thierry Frémaux, pioneer of the festival, is also the executive officer of the Cannes Film Festival. Similarities can be drawn between the Festival Lumière and his creation of the ‘Cannes Classics’ section at Cannes in 2004. This section honours works from the past alongside praising new ones from the official selection. ‘Cannes Classics’ selects around twenty films of all types, including shorts, features, documentaries and remastered films before they get released anywhere else in the world. Unlike Cannes, where mostly only professionals can attend, the Festival Lumière takes place in a bigger city and can accommodate a greater range of filmgoers.

By targeting the general public as its primary audience, the Festival Lumière provides audiences with the feeling of “belonging to a group, a cinephile community” where they can “meet with like-minded viewers” (Valck and Loist 186) and develop a further interest for cinema. Ticket prices are affordable compared to average cinema prices. They can be purchased for €6, which is almost half of the price for regular cinema tickets.

The professionals attending are either called to present films or to take part in the classic film market in order to serve the preservation remit of the festival. Indeed, the market allows professionals to meet and facilitate the distribution of remastered versions and ensure classic films are adapted to today’s digital era. In this respect, the Festival Lumière’s classic film market diverges considerably from Cannes’ film market, which trades in contemporary productions and is used as a vehicle for producers and film-makers to find connections for their future productions. Thereby, what makes the Festival Lumière unique is the omission of a red carpet and stars wanting to create buzz or fill their address book. The interest in professionals attending does not lie in finding potential partners for their productions but in showing that the old was once new and is worthy of preservation and attention.

The Festival was an original idea of Frémaux who, being passionate about cinema, wanted to create what he calls a “festival of the past” (qtd. in Ferenczi). Many commentators have wondered whether this idea could be an antidote to the gigantic scale (the buzz and publicity generated by attending celebrities) of Cannes in which he has been involved every year since 1999. Frémaux claimed that now that we have entered the digital era, an influential heritage film festival that remembers the graininess of 35mm and adapts these 35mm features to the modern age is needed more than ever. Such a festival ensures that masterpieces are not forgotten and are shown to a wider audience beyond a few cinephiles, thereby keeping the old world alive by adapting it to the new.

The Festival Lumière thus fulfils the “crucial task […] that is to defend cinema”, and more specifically classic cinema, in other words, paying reverence to it (Porton 4). Similar to the “sandwich process” theorised by Simon Field, which uses “bigger films to support the festivals and the small films” (qtd. in Porton 5), the Festival Lumière works on rendering the screenings interesting through a series of special events. It hosts retrospectives dedicated to iconic film-makers, invites actors, film-makers and composers to hold masterclasses and to curate a selection of classic films, and organises screenings of silent films with live musical accompaniment. Exhibitions and a flea market of cinema and photography memorabilia also render the discovery of heritage film more interesting and accessible. The festival’s main role, then, is educative but it aims at accessibility and relevance, hence the choice of contemporary artists to present the classic films.

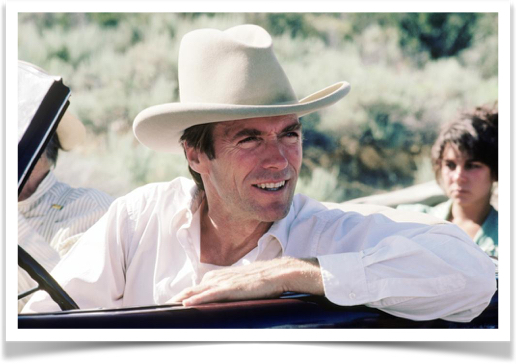

Film-makers from all over the world are thus called to take part in the festival. One might think that the festival would privilege French or Western film-makers, supposedly more known and popular amongst the general public. However, in the same way as it tries to showcase older films that people may not be familiar with, the festival also invites lesser known film-makers. For instance, in 2009, the festival called Serbian director Emir Kusturica to present Duck, You Sucker! (Giù la testa, 1971), Brazilian director Walter Salles to introduce Once Upon A Time in the West (1968) and Malian director Souleymane Cissé for Honkytonk Man (1982). The festival also created a selection called “The Art Noir” to show a range of different films noir from those starring Humphrey Bogart or Robert Mitchum, to remastered Korean films directed by Shin Sang-ok.

Film-makers from all over the world are thus called to take part in the festival. One might think that the festival would privilege French or Western film-makers, supposedly more known and popular amongst the general public. However, in the same way as it tries to showcase older films that people may not be familiar with, the festival also invites lesser known film-makers. For instance, in 2009, the festival called Serbian director Emir Kusturica to present Duck, You Sucker! (Giù la testa, 1971), Brazilian director Walter Salles to introduce Once Upon A Time in the West (1968) and Malian director Souleymane Cissé for Honkytonk Man (1982). The festival also created a selection called “The Art Noir” to show a range of different films noir from those starring Humphrey Bogart or Robert Mitchum, to remastered Korean films directed by Shin Sang-ok.

Frémaux appointed acclaimed French director Bertrand Tavernier as president of the Festival Lumière, someone sharing his cinephilia and ideas on the importance of heritage cinema. The influence of these two powerful figures of French cinema may certainly have contributed to the growing fame of the festival. The Festival Lumière is completely funded by the Region Rhône-Alpes and the Grand Lyon, and does not seem to be rendered hegemonic by Frémaux’s connection to Cannes. For instance, in 2009, the region and city of Lyon granted €1.2m to finance the festival, feeling that the project glorified the Lumière brothers, and thus a historical aspect of the region, alongside rendering heritage cinema more accessible.

The festival also greatly benefits the region and city. Already famous as a capital of gastronomy, for its local football team, the Olympique Lyonnais, and its annual Festival of Lights in December, the city of Lyon has undoubtedly attracted further cultural attention through the Festival Lumière, which has contributed to an increase in tourism over the past seven years (n.a. CCI Lyon Métropole). According to Ragan Rhyne, festivals are “international symbols of socio-political ambition” as well as sites of competition among new global cities (9). Thereby, the Festival Lumière is not only a way for Lyon to enrich itself via tourism, but it is also part of Frémaux’s ambition to make France the country owning the greatest heritage film festival in the world, in addition to already having the best known contemporary film festival in Cannes (Clarac).

The festival ends with a ceremony awarding a prize, the Prix Lumière, to one film-maker in order to honour their career. The prize is not awarded on the basis of the length of a celebrity’s career, the 2009 award went to Clint Eastwood, who made his debuts in the 1950s, and the 2013 award went to Quentin Tarantino, only making films since 1982. When awarded the prize, the festival organisers ask the filmmaker to shoot a remake of the Lumière Brothers’ Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon, 1895). Every film-maker is thus able to adapt his or her vision to the first film ever made. This neatly encapsulates the merging of the classic with the new. Although the Prix Lumière has only been given to Western filmmakers so far, we can hope that this trend stems from the newness of the festival, and, as it keeps on developing, the Prix Lumière will be extended to film-makers from other parts of the world.

The festival ends with a ceremony awarding a prize, the Prix Lumière, to one film-maker in order to honour their career. The prize is not awarded on the basis of the length of a celebrity’s career, the 2009 award went to Clint Eastwood, who made his debuts in the 1950s, and the 2013 award went to Quentin Tarantino, only making films since 1982. When awarded the prize, the festival organisers ask the filmmaker to shoot a remake of the Lumière Brothers’ Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon, 1895). Every film-maker is thus able to adapt his or her vision to the first film ever made. This neatly encapsulates the merging of the classic with the new. Although the Prix Lumière has only been given to Western filmmakers so far, we can hope that this trend stems from the newness of the festival, and, as it keeps on developing, the Prix Lumière will be extended to film-makers from other parts of the world.

France has long been known for its exception culturelle, a policy launched by the French Ministry of Culture under André Malraux in 1959, aiming at defending the national art (particularly for music and cinema) against an “Americanized” industry, considered as a threat to cultural diversity (Benbassat). The Festival Lumière diverges from the general French governmental state cultural policy because, although one of its aims is to elevate France’s status in the arts by being the stage of one of the greatest heritage film festivals worldwide, its emphasis is on a diversified film program not fully confined to the exception culturelle.

Its slogan, “A film festival for all”, has been associated with the protests supporting gay marriage and adoption in France in 2012, whose slogans included “weddings for all”. Even though Frémaux has claimed in an interview for GQ magazine that the slogan had been established prior to these protests, both events work towards diversity, and connecting the two places the Festival Lumière in a positive relation to France’s progressive political side.

We can hope that the success of this heritage film festival will result in expanding the general public’s open mindedness in relation to foreign films, or films considered unusual in some way, that the public will look to understand the past in order to appreciate present, and that it will raise awareness, and eventually influence the numbers of cinemagoers for contemporary foreign or art cinema at their release. We can only hope that the Festival Lumière will keep growing, the same way it has been growing until now, and continue making the unknown known, whatever its country of origin, and that it will always strive to expand diversity.

References

Benbassat, Daniel. “Qu’est-ce que l’exception culturelle française?” Contrepoints, 16 Jun. 2013. Web. 9 Mar. 2017.

Clarac, Toma. “Le Cinéma pour tous de Thierry Frémaux.” GQ Magazine, 20 Oct. 2014. Web. 9 Mar. 2017.

De Valck, Marijke, and Loist, Skadi. “Chapter Thirteen.” Film Festival Yearbook 1: The Festival Circuit. Ed. Rhyne Ragan and Dina Iordanova. St Andrews: St Andrews University Press, 2009. Print.

De Valck, Marijke. Film Festivals: From European Geopolitics to Global Cinephilia. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007. Print.

Ferenczi, Aurélien. “L’idée du Festival Lumière c’est d’évènementialiser le cinéma de patrimoine.” Télérama, 14 Oct. 2013. Web. 15 Jan. 2017.

Harbord, Janet. “Chapter Three.” Film Festival Yearbook 1: The Festival Circuit. Ed. Rhyne Ragan and Dina Iordanova. St Andrews: St Andrews University Press, 2009. Print.

n.a. CCI Lyon Métropole. Web. 9 Mar. 2017.

Porton, Richard Dekalog 03 On Film Festivals. London: Wallflower Press, 2009. Print.

Rhyne, Ragan. “Chapter One.” Film Festival yearbook 1: The Festival Circuit. Ed. Rhyne Ragan and Dina Iordanova. St Andrews: St Andrews University Press, 2009. Print.

Written by Charlotte Fuga (2017); Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Print This Post

Print This Post