A celebration of independent film-makers and art cinema, the International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) was established in 1972 by film programmer Hubert Bals under the original name, Film International Rotterdam. Known for his cinephilia, Bals was previously the organiser of the Cinemanifestatie festival in his hometown of Utrecht which centred around the “promotion of (commercial) cinemas” and screened films by established film-makers such as Akira Kurosawa and Louis Malle (de Valck 169). As Bals became exposed to more underground art films in his travels around Europe, his passion shifted from supporting the commercialisation of cinema to immersing himself in the experimental film scene and uncovering new talents, especially from developing countries. This led to the birth of IFFR. Since its opening night 45 years ago which had a very modest audience of seventeen spectators, the festival has grown to be one of the largest in the world, consistently attracting over 300,000 people and screening over 400 films across numerous venues.

IFFR falls under the category of specialised film festivals in its focus on Third World cinema and targeting of “art, avant-garde and auteurs” (de Valck 165). In 2017, the festival sported a new campaign, ‘Welcome to Planet IFFR’, which was designed to capture the festival’s inclusiveness as well as the vibrant concoction of screenings, masterclasses, installations and discussions on the future of virtual reality (VR). A new addition to this year’s line-up was the Black Rebels Programme, which even featured a masterclass from Moonlight (2016) director Barry Jenkins whose latest feature won IFFR’s Warsteiner Audience Award. The programme intended to open a conversation on the present cultural divide and racism spreading across democratic countries and to celebrate the “extensive influence of black culture on the arts” (Dutch News). Of the four sections of the programme – Bright Future, Voices, Deep Focus and Perspectives – the last had a clear focus on films that boldly tackle polarisation and sociocultural issues. Reflective of such concerns, the latest winner of IFFR’s Tiger Award, the equivalent of Cannes’ Palme d’Or, was Sanal Kumar Sasidharan’s Sexy Durga (2017), an experimental Indian-Malayalam drama which addresses the brutal degradation of women in India’s patriarchal society. Not only is the festival current in its address of contemporary issues, it also touches on recent technological developments. IFFR hosted Propellor Kickstart, the first of four Propellor Film Tech Hub events in 2017, encouraged people to devise new ways of producing and distributing films “in a world where seemingly more and more people would rather stay home than go to a movie theatre” (Dutch News).

IFFR falls under the category of specialised film festivals in its focus on Third World cinema and targeting of “art, avant-garde and auteurs” (de Valck 165). In 2017, the festival sported a new campaign, ‘Welcome to Planet IFFR’, which was designed to capture the festival’s inclusiveness as well as the vibrant concoction of screenings, masterclasses, installations and discussions on the future of virtual reality (VR). A new addition to this year’s line-up was the Black Rebels Programme, which even featured a masterclass from Moonlight (2016) director Barry Jenkins whose latest feature won IFFR’s Warsteiner Audience Award. The programme intended to open a conversation on the present cultural divide and racism spreading across democratic countries and to celebrate the “extensive influence of black culture on the arts” (Dutch News). Of the four sections of the programme – Bright Future, Voices, Deep Focus and Perspectives – the last had a clear focus on films that boldly tackle polarisation and sociocultural issues. Reflective of such concerns, the latest winner of IFFR’s Tiger Award, the equivalent of Cannes’ Palme d’Or, was Sanal Kumar Sasidharan’s Sexy Durga (2017), an experimental Indian-Malayalam drama which addresses the brutal degradation of women in India’s patriarchal society. Not only is the festival current in its address of contemporary issues, it also touches on recent technological developments. IFFR hosted Propellor Kickstart, the first of four Propellor Film Tech Hub events in 2017, encouraged people to devise new ways of producing and distributing films “in a world where seemingly more and more people would rather stay home than go to a movie theatre” (Dutch News).

Though not unique in its commitment to screening and supporting Third World cinema, the principle of cultural unity undoubtedly lies at the heart of the festival. Set in the bustling port city of Rotterdam where nearly 50 per cent of the population is non-Dutch and there are “no less than 186 different nationalities”, the festival aims to appeal to a culturally diverse community and expose its citizens to other cultures through the power of cinema (Rotterdam Unlimited). IFFR’s current managing and creative director, Bero Beyer, believes that “[t]he festival is for everybody, but also by everybody. We search all over the world […] to find films that make us feel. […] This results in an eclectic mix in which all nationalities of Rotterdam are represented” (Grievink). In showcasing contemporary films from all corners of the globe, the festival creates a real sense of community and counters the populist rhetoric spewed by “Islamophobic […] far-right leader Geert Wilders and his Party for Freedom” in the lead up to the 2017 Dutch general election (Paauwe). Given the recent “unstoppable rise in xenophobia […] [and] Islamophobia” in Rotterdam especially, it’s unsurprising that the latest edition of the festival focused so intently on the issue of polarisation (Yusuf). Beyer himself admits to the division in the city but believes that “Rotterdam in particular is ahead in terms of acknowledging it. You have to openly admit that there are major differences. Once that has happened, unity in action can be achieved” (Grievink).

Though not unique in its commitment to screening and supporting Third World cinema, the principle of cultural unity undoubtedly lies at the heart of the festival. Set in the bustling port city of Rotterdam where nearly 50 per cent of the population is non-Dutch and there are “no less than 186 different nationalities”, the festival aims to appeal to a culturally diverse community and expose its citizens to other cultures through the power of cinema (Rotterdam Unlimited). IFFR’s current managing and creative director, Bero Beyer, believes that “[t]he festival is for everybody, but also by everybody. We search all over the world […] to find films that make us feel. […] This results in an eclectic mix in which all nationalities of Rotterdam are represented” (Grievink). In showcasing contemporary films from all corners of the globe, the festival creates a real sense of community and counters the populist rhetoric spewed by “Islamophobic […] far-right leader Geert Wilders and his Party for Freedom” in the lead up to the 2017 Dutch general election (Paauwe). Given the recent “unstoppable rise in xenophobia […] [and] Islamophobia” in Rotterdam especially, it’s unsurprising that the latest edition of the festival focused so intently on the issue of polarisation (Yusuf). Beyer himself admits to the division in the city but believes that “Rotterdam in particular is ahead in terms of acknowledging it. You have to openly admit that there are major differences. Once that has happened, unity in action can be achieved” (Grievink).

Following Bals’ premature death, the prestigious Hubert Bals Fund (HBF) was set up in 1989 to honour his wishes of financing Third World film-making and has since brought over a thousand projects to fruition across the world. The fund is split into separate categories that cover all areas of film production, such as Script and Project Development Support, Postproduction Support and so on. The former is further split into “HBF Bright Future (for first and second time filmmakers) and HBF Voices (for filmmakers more advanced in their careers)” and both grant film-makers a modest €10,000 towards their project which is usually showcased at IFFR (Macnab). Previously, the fund was only available for projects that were filmed in developing countries listed on the Development Assistant Committee (DAC) list or in countries that rank low on the World Free Press Index such as Russia and Saudi Arabia. Academic Miriam Ross notes that this “restricted [film-makers] to working within a limited geographical scope”, arguing that this is a result of festivals not wanting to lose their image of supporting Third World cinemas by having projects shot elsewhere in non-developing countries (136). Recently, IFFR recognised this limitation and adjusted the rules of eligibility for the Script and Project Development Support fund whereby now a film-maker of a listed nationality can shoot a film anywhere and still be eligible for the fund. IFFR’s website states that the rules for the other categories are to also change in late 2017. This will ensure that emerging talents around the world can reap the financial and exposure benefits of the fund without limiting themselves geographically and creatively.

IFFR also expanded the fund into two new categories in 2014, the HBF+Europe: Distribution Support and HBF+Europe: Minority Co-production Support. The first is funded by Creative Europe’s new scheme of supporting international co-productions and it helps film-makers source international distributors. The only project to have been granted the fund so far was newcomer Visar Morina’s Babai (2015), a co-production between Kosovo, Germany, Macedonia and France which will use the money to distribute the film to Greece, Bulgaria and Egypt. The film, however, wasn’t screened at IFFR. On the other hand, one film which received the Minority Co-production Support was screened in IFFR’s 2017 programme. By the Time It Gets Dark (2016) from Thai director Anocha Suwichakornpong was a co-production between Thai production company, Electric Eel Films and its French counterpart, Survivance (iffr.com, 2015). The Minority Co-production grant is given to European producers to attach themselves onto international co-productions in order to boost the international awareness of the film.

Distribution is a new area for IFFR and one they are keen on expanding into. The festival has several schemes, all of which are designed to provide guidance and support to film-makers across the globe. One of these is IFFR Unleashed. As the festival can only offer limited financial support for distribution such as through the HBF, IFFR Unleashed was set up to support and offer expertise to film-makers in a changing climate where releasing films online is increasingly becoming the way forward, and multiple different platforms have emerged for film-makers to release their films on. IFFR’s current partnerships are with Doco Digital and Infostrada Creative Technology, the former acting as a mediator between film-makers and the digital retailers, the latter providing the conversion services so that films meet the technical requirements for a Video-On-Demand release on platforms such as iTunes and Google Play. IFFR’s ultimate aim is to release films to smaller and more specialised platforms such as MUBI. Unlike iTunes which offers a more mainstream service, MUBI’s audience are more inclined to watch “cult, classic, independent and award-winning films from around the world” which is more reflective of the films that IFFR encourages to be made, celebrates in the festival and wishes to distribute. In recognising that new and first-time film-makers may not comprehend the technicalities and logistics of releasing their films online, IFFR are keeping up with the times and offering invaluable knowledge that film-makers can take forward even after the festival.

Similarly, IFFR collaborate with the Film Office who primarily serve to advise film-makers and pair them up with relevant industry professionals. Film-makers are encouraged to have one-on-one conversations with mentors who can guide them on an array of issues including marketing strategies, budgeting and launching at festivals. Currently, there are four mentors who each have expertise in diverse areas allowing them to coach film-makers with varying needs. Additionally, the Film Office organise PRO panel discussions where professionals can discuss their own experiences and offer guidance. Essentially, the Film Office works to prepare film-makers for meeting the industry professionals who attend CineMart, the festival’s selective co-production market. Only 25 projects, from over 400 submissions, are chosen each year to be considered for a deal by CineMart’s wealth of bankers, sales agents and television stations and the market “serves as a filter to ensure that the qualities of both the projects and the financiers are reliable, making itself a seal of confidence” (Wong 148). The selected projects are screened during the four-day event that the market host every year as part of IFFR. CineMart also organise the Rotterdam Lab: a five-day training workshop for emerging producers. The lab’s partners, who range from the UK’s Creative Skillset to Nepal’s Docskool, must nominate the producers for the training scheme. Ultimately, IFFR’s collaborations are with organisations that are keen on nurturing talent, and often producers who have completed the training go on to produce films that are accepted onto IFFR’s programme in subsequent years.

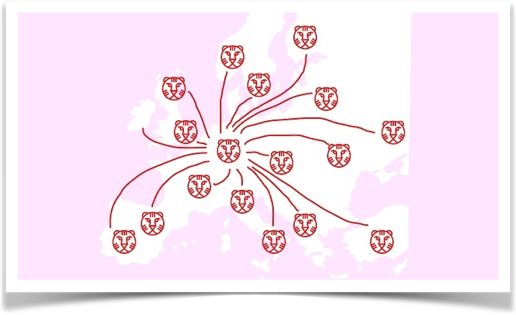

Determined as always to make their festival accessible to all, IFFR Live was introduced in 2015 so that audiences from around the world could watch the films and participate in the festival’s post-screening Q&As. In 2017, 46 European cinemas and two cinemas in Israel and Singapore simultaneously participated in six films screenings. IFFR also collaborated with VOD platform, Festival Scope, who temporarily screen films from the festival after their premieres at IFFR “to promote and help these films reach their deserved audiences” (Festival Scope). The platform screened the six films live on their website to reach audiences beyond Europe. At the end, audiences were able to ask the directors and actors present at the Q&A questions via social media using the hashtag #livecinema. This innovation enables the festival to expand its reach by including people who are interested in the festival but are unable to attend.

Until 2012, the festival relied primarily on the government and local council for funding. However, the country’s recent economic crisis has resulted in reduced financial support. In a blog on IFFR’s website, manager Martje van Nes comments on why the reduction did not drastically affect IFFR: “the urgency to source funds in other ways existed long before the current economic crisis. […] We have developed a close-knit network around us. Additionally, we do not want to get all our funds from the government, after all we are huge proponents of independent cinema” (iffr.com, 2012). The festival is now subsidised by various sponsors such as Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant and lottery organisation BankGiro as well as by private donations. One of the festival’s main sponsors since 2013 is Hivos, a global organisation whose aim is to bring about social and structural change by working with partners on campaigns and projects which benefit local communities. One of their goals in the ‘What We Do’ section on their website is ‘Freedom of Expression’ which shares IFFR’s aim of providing a platform for film-makers in countries which limit people’s freedom of speech.

Until 2012, the festival relied primarily on the government and local council for funding. However, the country’s recent economic crisis has resulted in reduced financial support. In a blog on IFFR’s website, manager Martje van Nes comments on why the reduction did not drastically affect IFFR: “the urgency to source funds in other ways existed long before the current economic crisis. […] We have developed a close-knit network around us. Additionally, we do not want to get all our funds from the government, after all we are huge proponents of independent cinema” (iffr.com, 2012). The festival is now subsidised by various sponsors such as Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant and lottery organisation BankGiro as well as by private donations. One of the festival’s main sponsors since 2013 is Hivos, a global organisation whose aim is to bring about social and structural change by working with partners on campaigns and projects which benefit local communities. One of their goals in the ‘What We Do’ section on their website is ‘Freedom of Expression’ which shares IFFR’s aim of providing a platform for film-makers in countries which limit people’s freedom of speech.

Despite constant developments, the festival remains “close to its original cinephile principles” and its consistent popularity has sparked the management’s desire to make IFFR a year-round event (de Valck 201). From students and budding film-makers, to technophiles and established directors from all over the world, there is no doubt that everyone is welcome at Planet IFFR.

References

“About – Festival Scope.” festivalscope.com. n.d. Web. 4 Apr. 2017.

“HBF announces first selection HBF+Europe: Minority Co-production Support.” iffr.com. 26 Jun. 2015. Web. 7 Apr. 2017.

“Home – Rotterdam Unlimited.” rotterdamunlimited.com. n.d. Web. 21 Mar. 2017.

“Inside IFFR: Martje van Nes about Sponsoring and Fundraising.” iffr.com. 19 Oct. 2012. Web. 21 Mar. 2017.

“What’s On: Rotterdam’s film festival welcomes you to Planet IFFR.” Dutch News. 20 Jan. 2017. Web. 6 Apr. 2017.

de Valck, Marijke. Film Festivals: From European Geopolitics to Global Cinephilia. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2007. Print.

Grievink, Elsbeth. “IFFR director: ‘Films can shape your worldview’.” Profielen. 26 Jan. 2017. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Macnab, Geoffrey. “IFFR: Hubert Bals Fund restructures.” ScreenDaily. 29 Jan. 2017. Web. 20 Mar. 2017.

Paauwe, Christiaan. “Don’t be relieved by the Dutch election—it’s done nothing to stop populism in Europe.” Quartz. 22 Mar. 2017. Web. 6 Apr. 2017.

Ross, Miriam. South American Cinematic Culture: Policy, Production, Distribution and Exhibition. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010. Print.

Wong, Cindy H. Film Festivals: Culture, People, and Power on the Global Screen. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2011. Print.

Yusuf, Hanna. “Racism in Rotterdam: how a diverse city got infected with Islamophobia.” The Guardian. 15 Mar. 2017. Web. 7 Apr. 2017.

Written by Sladana Tegeltija (2017); Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Print This Post

Print This Post