On 9 December 2016, the South Korean National Assembly voted for the impeachment of former president Park Geun-hye, an unprecedented event in the country’s political history. Among the various factors that led to the impeachment was civil unrest fuelled by the government’s lack of transparency. A key scandal contributing to the volatile climate was the artists’ blacklist: a 60-page document displaying a total of 9,473 names of artists who had voiced opinions against the regime and who were, as a consequence, put under state surveillance, barred from receiving state funding and, in some cases, prevented from producing or publishing their work (Steger).

The scandal is not without precedent. South Korea has a long history of film and media censorship, which dates as far back as the Japanese colonial period and runs through the fascist regimes of Park Chung-hee (1963-1979) – Park Geun-hye’s father – and, more recently, Chun Doo-hwan (1980-1988). During these regimes, government censors “had the authority to cut or re-edit films as they wished, or else reject a film entirely” (Paquet 14). The principal aims of the censors were to erase critical political messages from films and prevent negative depictions of the government or the country; the censors’ influence is explored in the second part of Kim Hong-joon’s video essay series My Korean Cinema (Naui hangugyeonghwa, 2003) which analyses the modifications made to Ha Kil-jong’s March of Fools (Babodeuli haengjin, 1975).

In late 1987, Chun’s successor Roh Tae-woo (1988-1993) declared films would no longer be subject to censorship during the preproduction stage (Park 124). This declaration kick-started a relaxation of censorship, which eventually allowed the flourishing of the Korean New Wave, characterised by filmmakers’ increased engagement with political matters. A pioneering example of Korean New Wave cinema is Park Kwang-su’s Chilsu and Mansu (Chilsuwa Mansu, 1988), which depicts two young working-class men as they become disillusioned with authority. The film culminates in an absurd clash between the protagonists and the police and media as they mistake the two young men’s inaudible yelling from atop a billboard for a subversive act. By the late 1990s, several films directly criticised past fascist regimes. Lee Chang-dong’s Peppermint Candy (Bakha Satang, 1999) explores the 1980s in reverse cronological order and reaches, near its conclusion, the May 1980 Gwangju uprising, a city-wide student protest against Chun’s regime that was violently suppressed by government troops, leading to over 1000 deaths (BBC).

After two decades of freedom from political censorship, Park Geun-hye’s predecessor Lee Myung-bak (2008-2013) drafted the blacklist. At the time, the document contained the names of 82 left-leaning artists who were put under government surveillance (Lee). Park Geun-hye (2013-2017) then dramatically increased that number, despite being publicly supportive of the Korean cultural industry, particularly the flourishing of the “Korean Wave”, a term which defines the recent success of Korean pop culture among international consumers. Through the slogan “Creative Korea”, her administration pushed for the increased export of cultural and entertainment products and, domestically, increased the control that the Ministry of Culture and Tourism could exert over such products (Kim 2018). However, this control allowed the Ministry – whose minister, Cho Yoon-sun, was jailed in 2018 – to abuse its power, thus increasing the number of blacklisted artists and the degree of surveillance that Park’s administration could maintain over the industry. It is important to mention that the list itself did not allow the Korean government to take direct legal actions against the blacklisted individuals. Nonetheless, it did have a direct effect on people’s careers and personal lives: for instance, blacklisted painter Hong Sung-dam claimed that he could no longer find any logistic companies willing to transport his work to a Berlin art festival, and that his wife was put under government surveillance (Kim 2018, 87).

The Korean blacklist is reminiscent of the filmmakers blacklist compiled in the US during the 1940s and 1950s with the similar aim of targeting artists who had left-wing sympathies and, therefore, were deemed connected to communist regimes. But on top of that, the majority of people on the Korean list were blacklisted for signing “one of the many joint statements issued to criticise Park’s handling of the Sewol ferry sinking” (YNA) or for speaking publicly about that particular incident. On 16 April 2014, the MV Sewol capsized off the coast of Donggeochado whilst carrying, along with other passengers, over 300 high-school students, the majority of which died. The rescue operations were mishandled, with the captain and crew being the first people to be rescued while all passengers were ordered to stay in their cabins (Ryall), a decision that led to the high death toll. The government sought to restrict depictions of the tragedy in film and the media and six months after the incident, the former mayor of Busan and leader of the Busan Film Festival, Suh Byung-soo, requested festival organisers not to screen the film The Truth Shall not Sink With Sewol (Daibingbel, 2014). This documentary, directed by reporter Lee Sang-ho and filmmaker Ahn Hae-ryong, was filmed around the site of the tragedy in the days immediately after the sinking. It captures the inefficacy of the rescue operations, juxtaposing them to newspaper headlines falsely stating that such operations were a success. It also follows the quest of Lee Jong-in, the head of Alpha Diving Corp., who attempted a rescue using his own equipment. The film shows that when Lee’s operation found no survivors, partially due to government forces actively getting in his way, news media falsely accused him of being a hindrance to the rescue efforts. Resisting government pressure, the organisers screened the documentary, and as a consequence the festival saw a budget cut of over 50% during the next two years (SCMP). Furthermore, the scandal that arose from the news that the state was seeking to influence the festival caused a number of filmmakers to try and boycott the event, which nearly led to it shutting down (SCMP).

The size of the outcry caused by the Sewol tragedy and the public discontent with Park’s administration affected several internationally famous artists. Directors Park Chan-wook and Bong Joon-ho are among the best known filmmakers to have appeared on the blacklist for speaking publicly against the regime. However, there are other causes which lead to blacklisting, such as in the case of actor Song Kang-ho. Song was blacklisted due to his starring role in The Attorney (Byeonhoin, 2013), a fictionalised account of the 1981 “Burim Case”, where 22 students were arrested on false accusations and a team of lawyers – which included Moon Jae-in, current president of South Korea – attempted to defend them in court. In an interview, Song addressed “the psychological impact of the blacklist, in which self-censorship had clouded his artistic judgment” (Kim 2018, 87), evidenced by his subsequent hesitation to star in another film critical of Chun’s regime, A Taxi Driver (Taeksi Unjeonsa, 2017)

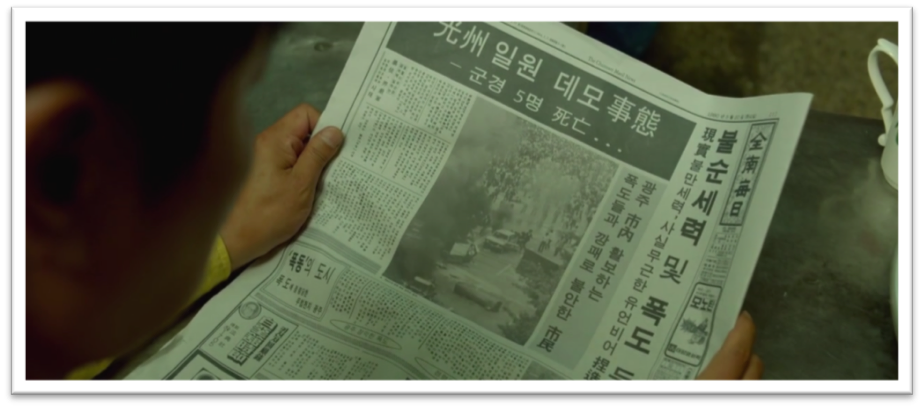

The main focus of A Taxi Driver is a dramatisation of the true story of German journalist Jürgen Hinzpeter (Thomas Kretschmann), the man responsible for distributing video footage of the Gwangju massacre worldwide, and the Korean taxi driver (Song Kang-ho) who safely escorted him in and out of the city. As well as an account of historical events, the film also serves as a poignant critique of media censorship and manipulation. During a scene at the start of the film’s third act, Song’s character contemplates abandoning Hinzpeter in Gwangju so that he may return to Seoul and take care of his young daughter. Whilst having lunch in a café on the way there, he overhears two patrons talking to a waitress about the mysterious events, possibly deaths, which are happening in Gwangju. One of the customers references a newspaper article, which states that innocent soldiers are being killed by a group of unruly protesters. The taxi driver, who recently witnessed the real events, holds up a newspaper and reads its headlines, which match the customer’s false claims. This ultimately convinces him to sneak back into Gwangju and save the journalist’s life. In his hesitation to work on the film, Song was aware that the topic would not have been well received by Park’s government, which was known for manipulating the news around instances such as the Sewol ferry sinking.

The extent of the blacklist and the climate of fear it caused are perhaps best evidenced by the number of institutions involved. Other than governmental forces, the Korean Film Council (KOFIC) was an active participant in the formation of the list. Upon the document’s official publication in April 2018, the new KOFIC president revealed the council’s direct involvement with at least 56 blacklisting cases (Kil). Independent filmmakers, who rely on the KOFIC for funding, were particularly influenced by its involvement with the blacklist. An example of this is Park Chan-kyong, Park Chan-wook’s brother, who was dumbfounded when his pitch for a horror film was rejected by the council and later found out it was due to his brother’s presence on the blacklist (Chow). Since its conception during Lee Myung-bak’s regime, the blacklist caused an unstable climate in the industry. In a media conference during the 2017 Cannes Film Festival, Bong Joon-ho stated: “It was such a nightmarish few years that left many South Korean artists deeply traumatised.” (qtd. in Kim 2018, 88). This serves as a frightening reminder of Korea’s fascist past and the youth of its democracy.

However, the blacklisting was stopped after Park’s impeachment. During his electoral campaign, current president Moon Jae-in promised a higher degree of government transparency compared to the previous administration. The website Koreanfilm.org comments: “the election of Moon, who enjoys a strong relationship with the film industry, signalled the start of a new era in which the government is expected to provide much more support to local filmmakers” (2018). After attending a screening of A Taxi Driver, Moon addressed the need to dig up information on the Gwangju Uprising, which is still scarce (Kim 2017). This is evidence of an attitude that goes against the suppression of information in the media. The lifting of the blacklist has also allowed for the production of films on what were previously considered taboo subjects. In 2017, together with A Taxi Driver, the Chun Doo-hwan era was also represented in 1987: When the Day Comes (1987, 2017). The film depicts the events that led to the so-called June Democratic Uprising, a pivotal episode in the country’s democratisation after the end of Chun’s regime. In 2018, the documentary Intention (Geunal, bada, 2018), which proposes a scientific investigation of the causes that led to the MV Sewol’s sinking, became the most viewed political-current affairs documentary of all time in South Korea (Koreaboo). Finally, although smaller independent productions are still in recovery after a decade of budget cuts caused by the blacklist, the new KOFIC leadership is a hopeful sign that conditions will now improve (Koreanfilm.org 2019).

References

BBC. “Flashback: The Kwangju Massacre.” BBC News. 17 May 2000. Web. Accessed 10 Mar 2019.

Chow, Vivienne. “No Longer Blacklisted, South Korea’s Park Chan-kyong Tries Again With Horror Film”. Variety. 3 Jul. 2017. Web. Accessed 5 Mar. 2019.

Kil, Sonia. “Korean Film Council Apology Reveals Devastating Effects of Blacklist Policy”. Variety. 5 Apr. 2018. Web. Accessed 5 Mar. 2019.

Kim, Ju Oak. “Korea’s blacklist scandal: governmentality, culture, and creativity.” Culture, Theory and Critique, vol. 59, no. 2, 2018, pp. 81-93. Print.

Kim, Rahn. “Presidents’ Choice of Films Shows Political Messages.” The Korea Times. 14 Aug. 2017. Web. Accessed 5 Mar. 2019.

Koreaboo. “Intention, a Sewol Ferry Documentary, Breaks Box Office Records in Korea”. Koreaboo. 28 Apr. 2018. Accessed 17 Mar. 2019.

Koreanfilm.org. “Korean Movie Reviews for 2017”. Koreanfilm.org. Updated 12 Oct. 2018. Web. Accessed 10 Mar. 2019.

Koreanfilm.org. “Korean Movie Reviews for 2018”. Koreanfilm.org. Updated 2 Feb. 2019. Web. Accessed 10 Mar. 2019.

Lee, Hyo-won. “South Korean Filmmakers Accuse Two Former Presidents of Blacklisting”. The Hollywood Reporter. 25 Sep. 2017. Web. Accessed 5 Mar. 2019.

Paquet, Darcy. New Korean Cinema – Breaking the Waves. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009. Print.

Park, Seung-hyun. “Film Censorship and Political Legitimation in South Korea, 1987-1992.” Cinema Journal, vol. 42, no. 1, 2002, pp. 120–138

Ryall, Julian. “South Korea ferry captain charged with manslaughter.” The Telegraph. 15 May 2014. Web. Accessed 10 Mar. 2019.

SCMP Associated Press. “South Korea’s film industry threatens to boycott Busan festival over claims of political interference”. South China Morning Post. Updated 20 Jul. 2018. Web. Accessed 5 Mar. 2019.

Steger, Isabella. “Former Korean president Park Geun-hye’s blacklist of artists filled 60 pages with 9,473 names.” Quartz. 10 Apr. 2018. Web. Accessed 5 Mar. 2019.

YNA. “Truth Committee: More than 9,000 politically active artists blacklisted under ex-President Park.” Yonhap News Agency. 10 Apr. 2018. Web. Accessed 10 Mar. 2019.

Written by Francesco Quario (2019); Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2019 Francesco Quario/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post