In the 1600s, fourteen women were sent to their graves in the Salem witch trials. These trials were one of the last examples of mass witch burning but a fascination with witches and witchcraft still remains. In the 1960s and 1970s the witch trials made a fresh apparition as, in the witchsploitation film, women were again burned and bound for public entertainment. However, instead of the old hag archetype with her threat to fertility, the modern witch was cast as a seductive young temptress, both praised and punished for her pornographic potential. In her film The Love Witch (2016), Anna Biller enacts a feminist revision of this imagery. Her film is timely, as the female witch is again experiencing a cultural renaissance. For instance, “Witches who are helping to introduce people to the Craft by spreading information via social media” operate under #witchesofinstagram, posting images of occult paraphernalia alongside feminist discourses (Krohn 19). This renewed fascination with the witch has even penetrated celebrity culture with Lana Del Rey casting a binding spell on Donald Trump via Twitter (Sisley). In light of this intersection of feminism and witchcraft, it is worth re-examining the sexual politics of the witchsploitation film.

Emerging in the 1930s, exploitation films were the cinematic equivalent of freak shows. On the premise that they offered audiences a moral education, these films covertly perpetrated images that bordered on pornography. For instance, whilst a film such as Sex Madness (1938) appears to propagandise against licentious behaviour, at the same time it engages in the proliferation of sexual images. As a result, Eric Schaefer writes that exploitation films focused on “any […] subject considered at the time to be in bad taste” (5). By the 1960s, the increasing influence of pornography, along with the free love movement, meant that the coy striptease of the exploitation flick had become a full-on free-for-all. These films were no longer accompanied by an educational disclaimer, but were purposefully designed to disturb and arouse. As well as this, the 1960s also saw a renaissance of interest in occult practices, as the rising popularity of Wicca converged with the psychedelic underground’s love for all things esoteric. Therefore, witchsploitation emerged as a product of “the occult-infused LSD experience in the 1960s” (Bebergal 42).

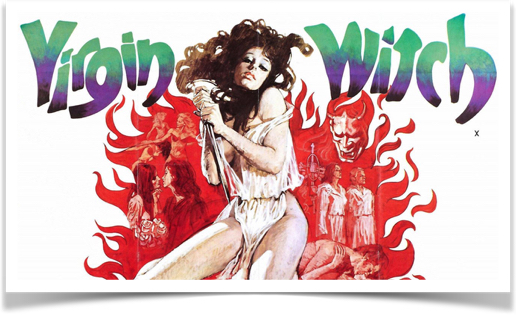

A defining example of the witchsploitation film can be found in Ray Austin’s Virgin Witch (1972), which follows a young model as she becomes embroiled in a coven of lesbian witches. Virgin Witch’s pornographic appeal is evident by its endorsement in the December 1970 issue of Mayfair, a popular British adult magazine. In terms of genre, witchsploitation can be described as a strange brew of melodrama, horror and soft-core pornography, and typically fixates on the story of a young woman who is introduced to black magic and freed from her sexual inhibitions. Prioritising visual pleasure over narrative coherence, these films are usually characterised by a style of acting that oscillates from wooden to overwrought. However, despite their reputation as bad movies made in bad taste, films such as The Love Witch have used tropes and stereotypes from witchsploitation to revise the witch’s bad reputation in cinema.

A defining example of the witchsploitation film can be found in Ray Austin’s Virgin Witch (1972), which follows a young model as she becomes embroiled in a coven of lesbian witches. Virgin Witch’s pornographic appeal is evident by its endorsement in the December 1970 issue of Mayfair, a popular British adult magazine. In terms of genre, witchsploitation can be described as a strange brew of melodrama, horror and soft-core pornography, and typically fixates on the story of a young woman who is introduced to black magic and freed from her sexual inhibitions. Prioritising visual pleasure over narrative coherence, these films are usually characterised by a style of acting that oscillates from wooden to overwrought. However, despite their reputation as bad movies made in bad taste, films such as The Love Witch have used tropes and stereotypes from witchsploitation to revise the witch’s bad reputation in cinema.

In The Love Witch, Elaine (Samantha Robinson) is a glamorous young witch who casts love spells in the hope of obtaining perfect romance. However, her spells backfire, turning her quest for love into an accidental murder spree. Elaine seems to inhabit a Hollywood set where the paradisiacal vision of California in the 1960s never fades. But this is a paradise interrupted – a modern car here, a cell phone there – and Elaine’s carefully crafted phantasmagoria constantly threatens to dissolve. The aesthetic of witchsploitation is evoked by the tarot card Technicolor of the set design and the camera’s voyeuristic interest in the minutiae of rituals. Curiously, these rituals are given the same amount of screen time as a scene in which Elaine removes her bloody tampon and submerges it in her own urine. Therefore, the intimate workings of the female body are exposed in a way that cannot be said to be being exploited for a pornographic purpose. Instead, female vulnerability and power are simultaneously revealed. Elaine is not the virgin led astray; rather, she channels her dangerous powers through her sexual prowess whilst always remaining attuned to her own body (Russell 65).

In The Love Witch, Elaine (Samantha Robinson) is a glamorous young witch who casts love spells in the hope of obtaining perfect romance. However, her spells backfire, turning her quest for love into an accidental murder spree. Elaine seems to inhabit a Hollywood set where the paradisiacal vision of California in the 1960s never fades. But this is a paradise interrupted – a modern car here, a cell phone there – and Elaine’s carefully crafted phantasmagoria constantly threatens to dissolve. The aesthetic of witchsploitation is evoked by the tarot card Technicolor of the set design and the camera’s voyeuristic interest in the minutiae of rituals. Curiously, these rituals are given the same amount of screen time as a scene in which Elaine removes her bloody tampon and submerges it in her own urine. Therefore, the intimate workings of the female body are exposed in a way that cannot be said to be being exploited for a pornographic purpose. Instead, female vulnerability and power are simultaneously revealed. Elaine is not the virgin led astray; rather, she channels her dangerous powers through her sexual prowess whilst always remaining attuned to her own body (Russell 65).

Biller has openly voiced a dislike for the comparison of her films to exploitation genres. Discussing her first film Viva (2007), she states “I was extremely angry […] ‘Viva’ got talked about like a copy or pastiche of a sexploitation film and not as something that maybe borrows a little bit from those films” (qtd. in Erbland). Rather than using pastiche, Biller uses postmodernist references to initiate a critique of the kind of reductive sexual politics that exploitation films engender. For instance, in The Love Witch, the dialogue is deliberately stilted, with Elaine often situated as a one-dimensional figure from a Playboy centrefold. However, this wooden atmosphere alludes to the emotional dislocation of the characters. Elaine does not understand the organic quality of love – rather, she believes it is something to be orchestrated through a seductive spell. She enjoys the superficial surface of love, but as soon as men become emotionally invested in her, she disposes of them. Therefore, Elaine’s cold personality exacerbates the hysterical reactions of her lovers, illustrating how the pornographic female must become necessarily estranged from her emotions.

Superficiality pervades every aspect of The Love Witch, with Biller describing Elaine as “a glamour witch” (qtd. in Tsjeng). However, the use of glamour is evocative as “an understanding of the root of the word ‘glamour’ reveals a relationship between feminine allure and magic”, although “the primary meaning […] has been displaced by the idea of surface or physical feminine allure” (Moseley 404). Therefore, in The Love Witch, glamour can be seen as an allegory for how cinema reduces female power to an attractive façade. For instance, two young twins are instructed by the coven to use make-up to ensnare lovers. This focus on the use of artificiality interrogates the assumption that women’s ability to wield power is directly quantified by their visual appeal. This is also shown in a scene in which Elaine lays in bed in her underwear, as the voice of her ex-husband can be heard praising her for losing weight and wearing make-up. As a result, Elaine’s glamorous image is both analogous to her magical abilities and her superficial existence as a sexually desirable woman. This relationship between make-up and magic is further illustrated as the camera repeatedly zooms in to Elaine’s heavily made-up eyes as she casts her love spells, as though her signature blue eye shadow is the true key to her power. However, after the magic has served its purpose, Elaine is seen waking up with mascara smeared across her face, an image that suggests the undoing of a façade. In all this, Biller reveals the witch to be a real, multi-faceted and flawed woman, rather than a disempowered pin-up.

Biller’s The Love Witch is not the only piece of contemporary film-making to enact a feminist re-evaluation of the witch. Roger Eggers’ The Witch (2015) also uses this archetype to interrogate patriarchal structures. Set in the 1600s, the film focuses on a family who are banished from their Puritan settlement as a result of a disagreement over scripture. The patriarchal figure William (Ralph Ineson) constructs an absolute moral world for his family, which is unsettled as his eldest daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy) enters into the unholy realm of female puberty. Thomasin’s coming-of-age begins as the family are beset by evil, and she is demonised as the cause. However, Thomasin’s joining with the witches’ coven represents a moment of liberation rather than capitulation. Her process of becoming-witch is also a process of becoming-woman as in the forest she is removed from the patriarchal gaze, able to reinvent herself as an autonomous sexual being. This feminist perspective is acknowledged by Jex Blackmore of activist organisation the Satanic Temple, as she states, “Eggers’ film refuses to construct a victim narrative […] instead it features a declaration of feminine independence” (qtd. in Pierce).

Biller’s The Love Witch is not the only piece of contemporary film-making to enact a feminist re-evaluation of the witch. Roger Eggers’ The Witch (2015) also uses this archetype to interrogate patriarchal structures. Set in the 1600s, the film focuses on a family who are banished from their Puritan settlement as a result of a disagreement over scripture. The patriarchal figure William (Ralph Ineson) constructs an absolute moral world for his family, which is unsettled as his eldest daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy) enters into the unholy realm of female puberty. Thomasin’s coming-of-age begins as the family are beset by evil, and she is demonised as the cause. However, Thomasin’s joining with the witches’ coven represents a moment of liberation rather than capitulation. Her process of becoming-witch is also a process of becoming-woman as in the forest she is removed from the patriarchal gaze, able to reinvent herself as an autonomous sexual being. This feminist perspective is acknowledged by Jex Blackmore of activist organisation the Satanic Temple, as she states, “Eggers’ film refuses to construct a victim narrative […] instead it features a declaration of feminine independence” (qtd. in Pierce).

The witch is the ultimate symbol of female terror and “the myth of the witch is essentially […] a product of male fears” (Moseley 71). She embodies many of men’s most deep-rooted fears, including castration anxiety. For instance, in the Catholic propaganda text the Malleus Maleficarum (1487) it is claimed that witches would steal men’s penises, keeping them like pets. Simultaneously, she is also the ultimate feminist symbol as a figure capable of unsettling patriarchal structures. In this light, it makes sense that “the witch is back at the fore of the collective imagination […] casting a spell over fashion, pop culture and academia with her badass symbolism” (Madsen). Despite coinciding with Second Wave feminism, witchsploitation films did not emerge out of this same rhetoric. In these films, the feminist potential of the witch is “diluted” as she is presented as a “temptress leading men to their doom” through her power, not to steal members, but to stimulate them (Russell 71). Witchsploitation films of the 1960s and 1970s, then, exist in a pornotopia, where the “the function of plot […] exists purely to provide as many opportunities as possible for the sexual act to take place” (Carter 12). However, Biller’s representation of the witch can be seen as prescient and both provocative and political. The Love Witch was released only three days after high priest of misogyny Donald Trump was elected as the next President of the United States. On this timeliness, Biller remarks, “as soon as the election happened, the reviews became very different […] and those scenes […] with the near-rape and the crowds shouting: ‘Burn the witch!’ – that all feels pretty Trumpian all of a sudden” (qtd. in Patterson).

The Love Witch challenges the witch’s prostration by allowing “the proverbial monster [to] turn on its creator, and force a confrontation” (Russell 71). For instance, Biller states, “I am in conversation with the pornography that’s all around us” (qtd. in Patterson). In an era where young feminists, who grew up with Sabrina the Teenage Witch (1996-2003) have come of age, the revival of the witch as a feminist figure seems appropriate. This appeal is noted by Slutist founder Kristen Korvette, as she claims, “young women are looking for an archetype outside the tired virgin-whore binary that we’re offered, and the witch can do just that” (Madsen). After all, when President Donald Trump advocates grabbing women by the pussy, it is empowering to remember those witches with their power to make penises disappear in abject fear.

References

Bebergal, Peter. Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll, Penguin, 2014.

Carter, Angela. The Sadeian Woman, Virago, 1979.

Erbland, Kate. “5 Tips For Making a Badass Feminist Movie From the Director of ‘The Love Witch’.” IndieWire. 18 Nov. 2016. Web. 5 Mar. 2017.

Krohn, Elisabeth. “#Witchesofinstagram.” Sabat I: The Maiden Issue, Sabat Magazine, 2016, pp. 16-21.

Madsen, Susanne. “It’s the season of the witch.” Dazed. 26 May 2016. Web. 5 Mar. 2017.

Moseley, Rachel. “Glamorous Witchcraft: Gender and Magic in Teen Film and Television.” Screen, Vol. 43, No. 4, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp. 403-417.

Patterson, John. “The Love Witch director Anna Biller: ‘I’m in conversation with the pornography all around us’.” The Guardian. 2 Mar. 2017. Web. 5 Mar. 2017.

Pierce, Scott. “The Witch is Sinister, Smart, and Wildly Feminist.” Wired, 19 Feb. 2016. Web. 5 Mar. 2017.

Russell, Sharon. “The Witch in Film: Myth and Reality.” Planks of Reason: Essays on the Horror Film, edited by Barry Keith Grant and Christopher Sharrett, Scarecrow Press Inc., 2004, pp. 63-71.

Tsjeng, Zing. “The Woman Behind ‘The Love Witch’ on Creating a Film for Female Pleasure.” Broadly. 11 Nov. 2016. Web. 5 Mar. 2017.

Schaefer, Eric. “Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!” A History of Exploitation Films, 1919-1959, Duke University Press, 1999.

Sisley, Dominique. “Lana Del Rey ‘to cast ritual binding spell on Donald Trump’.” Dazed. 24 Feb. 2017. Web. 5 Mar. 2017.

Written by Willow Hindle (2017); Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Print This Post

Print This Post