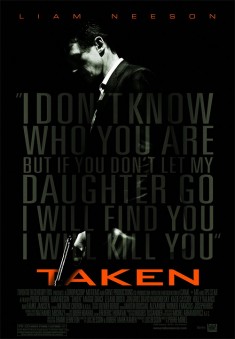

Plot Los Angeles, present day. Former spy Bryan lives a quiet life and is trying to rebuild his relationship with teenage daughter Kim. Kim and her friend Amanda leave for a trip to Europe. At the airport in Paris, they share a taxi with a young Frenchman. He reveals details of the apartment where the girls are staying to a gang of Albanian sex traffickers. The traffickers kidnap the girls. Bryan flies to Paris, knowing he has only days to save his daughter before all trace of her is lost. He tracks down the Albanians but Amanda is already dead and there is no sign of Kim. Bryan discovers that senior French police officers and politicians are involved in the sex trafficking. He tortures the ring leader of the Albanian gang to find the whereabouts of his daughter. In the basement of a house where a swanky function is being held, he finds an auction going on in which his daughter is the main lot. Bryan is knocked out and captured before he can rescue her. He escapes and races to catch up with the boat on the Siene – Kim is on board, having been bought by a rich Arab. Bryan kills the Arab’s henchmen and rescues her, bringing her home safely to America (adapted from Macnab 74).

Film note Taken, a popular thriller directed by Pierre Morel and produced by Luc Besson’s French production company Europa Corp, is a highly problematic text in several ways. Firstly, the film’s PG-13 rating awarded by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) undercuts the violent subject matter of torture, rape and revenge; secondly, the film misrepresents the mechanics of contemporary sex-trafficking in order to construct non-US nations as corrupt and sexually deviant; finally, Taken recalls an earlier cycle of revenge films and their objectification of female characters, disregarding the pain of its imperilled teenage daughter in order to emphasise her father’s anxiety and agency.

The PG-13 rating Taken was awarded a PG-13 rating by the MPAA for “intense sequences of violence, disturbing thematic material, sexual content, some drug references and language.” The PG-13 rating was introduced in 1984, with Red Dawn (1984) the first widely distributed film to receive the rating. The rating was created to find a middle ground between the G rating aimed at families and children, and the much more extreme films that the R rating covers. It came in light of films such as Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984) and Gremlins (1984); films aimed at a wide audience, but with occasionally violent content, thus requiring a more serious parental warning for young children. Steven Spielberg said of the rating “I created the problem and I also supplied the solution […] I invented the rating” (qtd in Anonymous, “Gremlins…”). The MPAA emphasise how the rating is not tied to a specific age,thus allowing parents to make the decision about what is suitable for their children to watch, (however the rating clearly suggests that the films will be appropriate for children over the age of 13).

MPAA ratings have often been the subject of controversy about what is deemed acceptable or unacceptable for young children to watch. Recently films such as The Dark Knight Rises (2012), and The Hunger Games (2012) have been awarded a PG-13 rating despite dark content and adult themes (Merrill). Concerns have also been raised about the heavy advertising of films with PG-13 ratings on children’s television channels like as Nickelodeon and Cartoon Network. Susan Linn suggests that, while the MPAA may assess the marketing of a PG-13 film, it “focuses on the content of the ads, not whether the film advertised is appropriate for a younger audience.” Furthermore, a recent study has shown that “although the MPAA attempts to rate films with potentially harmful content in its Restricted (R) category, its ratings permit as much violent content in films appropriate for children over 12 (PG-13) as in R-rated films” (Bleakley, Romer and Jamieson).

For its cinematic release Taken was rated at PG-13, however on DVD an unrated version was released, a so-called “‘harder cut”. This revealed the changes that had been made to ensure the cinematic release was a PG-13: scenes of women being sold into sex slavery were shortened, heroin wounds on a character’s arm were removed, as was a close up on the face of a corpse, and there is generally less focus upon the working prostitutes. However, the most significant change occurs when Bryan (Liam Neeson) is interrogating Marko (Arben Bajraktaraj) on the whereabouts of his daughter. In the theatrical release, Bryan attaches electrical cables to the metal chair to which is Marko is tied; in the uncut version Bryan rams two nails into Marko’s thighs and attaches the currents to them instead. In both versions of the scene after Bryan has the information that he needs he flips on the current and leaves Marko to be electrocuted to death.

The cuts made to Taken work to make it more appropriate for a younger target audience, with less violence and fewer explicit references to the drugs and sex trade. However, I would argue that the themes portrayed and explored in the film are the main contributor to its adult nature. The fact that Taken deals with sex trafficking and rape, and contains extreme violence perpetrated by its “hero”, is concerning when one takes into account how it was marketed at (and seen by) an adolescent audience. This audience was crucial to the film’s success. Statistics show that on average a PG-13 rated film will make around three times as much money as an R rated film. There are only six R rated films in the “Top 100 Domestic Grosses” of all time list for the US (as compiled by boxofficemojo.com), and since the creation of the PG-13 rating films classified this way have consistently filled the “Top 10 Lists” for each year. In 2008, the year of Taken’s release, six of the top ten grosses for the year were rated PG-13, with the remaining four rated G. In light of this, it clearly makes the most economic sense to edit Taken in such a way as to achieve a PG-13 rating for theatrical release, a strategy that moreover allows for greater DVD sales thanks to the presence of two versions of the film in the home entertainment marketplace.

Sex-trafficking and masculinity Taken was released within a few years of a number of other films dealing with sex trafficking, including Holly (Guy Moshe, 2006), Trade (Marco Kreuzpaintner, 2007), Shuttle (Edward Anderson, 2008) and The Whistleblower (Larysa Kondracki, 2010). Taken was certainly the most successful of these, and the striking differences in its treatment of the subject matter could account for this.

Nonetheless, there are similarities between these films. Firstly, all five films give great importance to the idea that femininity and purity need to be protected. Casey Ryan Kelly argues that Taken “uses an icon of feminine virtue to excuse the use of force against uncivilised men and invites popular audiences to sympathise with extreme acts of cruelty” (404). Bryan’s actions are justified by his need and desire to rescue his daughter, and more specifically her virginal purity. In Holly the girl being rescued from having her virginity sold to the highest bidder is just 13 years old; the same is true of the captive in Trade. In Shuttle, though the girls are not virgins, the mere fact that they are caucasian associates them with purity. (Trade is the only of these films to suggest that young boys are sex-trafficked as well as girls.)

In Taken, Bryan’s kidnapped daughter Kim (Maggie Grace) can be considered nothing more than a plot device to enable “a risable male re-empowerment fantasy” (Jolin). For the majority of the film she is absent from the screen, apparently just waiting to be rescued, and makes no attempt to take matters in her own hands. Before she has even been kidnapped she has resigned herself to the fact that this will occur, because her father has told her as much. Other films in this cycle do not necessarily depict women as such passive agents. In The Whistleblower, protagonist Kathryn (Rachel Weisz) is the driving force behind attempts to disband a sex-trafficking ring in Bosnia. In Holly the title character is shown to be much more feisty than Kim: on a number of occasions she attempts to escape those trying to sell her. In Shuttle Mel (Peyton List) and Jules (Cameron Goodman) repeatedly attempt to escape their predicament as there is nobody else able to help them. The passivity of Taken’s Kim thus highlights the conservative logic of the film, since it allows Bryan to assert his necessity as a patriarch. Even though Bryan is positioned as an absent father, he is nonetheless a righteous and respectable one: Kim’s mother and stepfather show a desire to “quicken Kim’s entry into womanhood” (Kelly 407), making them reckless and uncaring in the moral universe the film constructs. This reinforces traditional ideas of the nuclear family, and the imperative for the father, regardless of his previous actions, to be at the head of that family unit.

This accords with Jennifer Jozwiack’s suggestion that it is through the “impenetrability of a paternal masculinity that the Unites States is narratively constructed as a privileged and powerful nation” in sex-trafficking films (23). Bryan’s excursion into the sex trade does not damage him, meaning the US emerges as a bold and impenetrable entity. The same is true of Holly, in which the depiction of non-American men as deviant works to highlight the restrained sexuality of the male protagonist (Jozwiack 24) Taken’s success could in part be attributed to the representation of the US as distant and far removed from the ugly sex-trade, which is shown to be run by various European and Arab agents. By contrast, Shuttle, The Whistleblower and Trade all implicate the US and American citizens in the sex trade: Shuttle sees American women being trafficked upon their return across the border from Mexico by two American men; The Whistleblower shows American troops on a peacekeeping mission in Bosnia complicit in networks of forced prostitution; and Trade shows Mexican girls being smuggled across the border to be kept as sex slaves.

As such, these other films show that, as Katie Ann Martin asserts, “The U.S. is the second largest destination country for sex trafficking victims” (65). Edward Schauer and Elizabeth Wheaton write in 2006 that they expect human trafficking to surpass drug trafficking as the number one international crime in the next ten years (147). In light of this, it would seem that the most successful of films about sex trafficking, Taken, has been the least true to realities of the trade. It stands to reason that movies that show the US, or its citizens, either as complicit in human trafficking operations, or as the instigator in such operations would be unpopular with American audiences.

Revenge film Taken can also be considered a revenge film, and as an extension of the rape-revenge cycle of films from the 1970s and 80s. Bryan Mills is not dissimilar from Charles Bronson’s Paul Kersey of Death Wish (1974): they both engage in extreme violence as they seek vengeance for what has happened to the women in their lives. Death Wish portrays some of the conservative sensibilities of the time, as we see Paul convert from a liberal who is tolerant of urban crime to a much more radically conservative individual (Ryan and Kellner 89). In both Death Wish and Taken it is an attack on femininity that motivates the male protagonist. As Ryan and Kellner argue of the earlier film’s villains, “In Death Wish the audience remains external to the robbers; their murder is justified by a certain cinematic point of view” (94). Furthermore, the representation of passive femininity identified in Taken is similarly displayed in Death Wish. Alexandra Heller-Nicholas argues that the latter film “makes literal the idea that female bodies are nothing but spaces for male expression” (57). Though she focuses on moments which female characters are spray-painted by their attackers, I would argue that this objectification is alluded to at the film’s opening as Kersey’s wife Joanna allows him to take pictures of her.

Another film of this rape-revenge cycle, I Spit On Your Grave (1978), assertively depicts rape as ugly, terrifying and brutal, making the rape scene so long (twenty-five minutes) that protagonist Jennifer’s revenge actions appear completely justified in light of the horrors that she (and the viewer) have been put through (Heller-Nicholas 37). The 2010 remake of I Spit On Your Grave deviates from the original in a number of ways. The addition of a corrupt Sherriff and his reprehensible actions marks a crucial shift, since Jennifer’s trust in the institutions put in place to protect her is undermined and exploited. In this way, her logic for seeking revenge outside the legal system is watertight. By contrast, the 1978 version does not show Jennifer asking for any help in exacting her revenge, and her attacks on the men who raped her are highly eroticised.

In these films rape scenes are torturously long in order to justify the revenge actions. In Taken no rape is demonstrated at all, yet Bryan’s status as a patriarch means that he appears unquestionably justified in his violent attacks. Law Abiding Citizen (2009), though it doesn’t involve rape, does not deviate far from the revenge narrative demonstrated in this canon of films. Heller-Nicholas’s words on this film are applicable to Taken, when she suggests it positions “rape as a property crime between men rather than acknowledging the subjective trauma of the female experience of sexual violence” (159). In this sense both Taken and Law Abiding Citizen are a turn back to the conservative traditions demonstrated in Death Wish, whereas both versions of I Spit On Your Grave show a woman who – in spite of her circumstances – has managed to seek revenge without male help. The more liberal ideologies of the I Spit On Your Grave remake could be a contributing factor in the film being less successful than its source. Though Taken also shows a disdain and cynicism towards the authorities, this is directed toward French rather than American institutions, and so it is much easier for a US audience to swallow. The rape-revenge plot has even become a part of many mainstream films in recent years, perhaps most surprisingly in the tween flick Twilight Saga: Eclipse (2010).

Taken’s treatment of the Eastern European and Arab other is also telling. An anonymous Time Out reviewer claims that the film’s pace of action “leaves no time to ponder the […] borderline racist portrayals of vicious Albanian gangster and sleazy Arab businessmen” (Anonymous, “Taken”). However, I am more inclined to agree with Guardian reviewer Xan Brooks, who describes the film as “slick, dubious, [and] morally bankrupt.” Taken presents those who are not American as both corrupt and expendable: the sex-trafficking ring is made up of Arabs and Albanians, and the Parisian police force can’t be trusted. As Jolin describes, “If a good little teenaged Caucasian strays even an inch beyond the mighty US of A’s borders, she’s pale prey to every godless, sex-mad, drug pushing foreigner out there.” As we have already seen, this thinking is problematic, and ignores the fact that the US is one of the prime destinations for trafficked individuals. Nonetheless, this type of thinking is what drives Bryan and what makes his actions appear acceptable.

Racism towards Arabs in Hollywood cinema is nothing new. A 2001 survey of US cinema by Jack Shaheen finds that Arabs are persistently identified as sexually-threatening, criminal, and violent toward women. Shaheen begins a later study with the suggestion that “Malevolent stereotypes equating Islam and Arabs with violence have endured for more than a century” (2013, 1). Even films as seemingly innocent as Disney’s Aladdin (1992) serve to reinforce the violent Arabian stereotype (Shaheen 2001, 50–54). With the long standing history of poorly represented Arabs in Hollywood cinema it is unsurprising that in Taken it is ultimately an Arab sheik that purchases Kim. It is interesting to note the striking difference in this sense between Taken and Shuttle. For the girls in Shuttle are safe while they are in Mexico, on the far side of the American border, it is only when they cross the border to the US that they get into danger. They are then taken by two seemingly harmless and anonymous-looking men, not threatening Eastern Europeans. In this way, the logic of the “other” that is accepted in Taken is entirely subverted making the US the place of danger, and the Mexican “other” where they are safe.

Taken, then, is a conservative revenge narrative, and as such can be productively associated with the rape-revenge cycle of films from the late 70s and early 80s in Hollywood. Its portrayal of the sex trade, which is inaccurate, is far more palatable to a US audience than the other films explored here. The film represents passive female characters and racist caricatures in order to justify the hero’s actions. As Manohla Dargis puts it, “Happily for Bryan, nothing brings an estranged daughter back into the patriarchal fold faster than the threat of being served up like a bonbon to a salivating, knife-wielding sheik from the Republic of Cinematic Stereotypes.” Bryan is the epitome of the American patriarch, taking justice into his own hands and winning his daughter back against all the odds, his training in US defence and intelligence tellingly leading to this victory.

References

Anonymous. “Gremlins, Bloody Hearts, Big Changes: The PG-13 Rating Turns 20.” CNN. 24 Aug. 2004. Web. 04 Jan. 2014.

Anonymous. “Taken (15).” Time Out. 05 Sep. 2008. Web. 28 Nov. 2013.

Bleakley, Amy, Daniel Romer and Patrick E. Jamieson. “Violent Film Characters’ Portrayal of Alcohol, Sex and Tobacco Related Behaviours” Pediatrics [online journal] Dec. 2010. Web. 27 Dec. 2013.

Brooks, Xan. “Taken.” The Guardian. 26 Sep. 2008. Web. 28 Nov. 2013.

Dargis, Manohla ”Vigilante Daddy Avenges Kidnapping.” New York Times. 29 Jan. 2009. Web. 28 Nov. 2013.

Heller-Nicholas, Alexandra. A Critical Study: Rape-Revenge Films. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. 2011. Print.

Jolin, Dan. “Taken.” Empire. Undated. Web. 28 Nov. 2013.

Jozwiack, Jennifer. “My Father, the Hero: Paternal Masculinities in Contemporary Sex Trafficking Films.” In From Bleeding Hearts to Critical Thinking: Exploring the Issue of Human Trafficking [conference proceedings]. Ed. Kamala Kempadoo and Darja Davydova. Toronto: Centre for Feminist Research, 2012. 20-25. Print.

Kelly, Casey Ryan. “Feminine Purity and Masculine Revenge-Seeking in Taken (2008)” Feminist Media Studies 14.3 (2014): 403–418. Print.

Linn, Susan. “Reform Movie Marketing, Too.” The New York Times [Opinion Pages]. 21 Nov. 2013. Web. 4 January 2013.

Macnab, Geoffrey. “Review: Taken.” Sight & Sound 18.11 (2008): 74. Print.

Martin, Katie Ann. “Domestic Violence, Sexual Assault, and Sex Trafficking in the Media: A Content Analysis” Unpublished Master’s Theses, East Michigan University. Paper 469 (2013). Print.

Merrill, Cristina. “’Dark Knight Rises’ Gets PG-13 Rating After ‘Bully’, ‘Hunger Games’ Controversy.’ International Business Times. 11 Apr. 2012. Web. 4 Jan. 2014.

Ryan, Michael and Douglas Kellner. Camera Politica: The Politics and Ideology of Contemporary Hollywood Film. Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press. 1990. Print.

Schauer, Edward and Elizabeth Wheaton. “Sex Trafficking into the United States: A Literature Review.” Criminal Justice Review, 31.2 (2006): 146-169. Print.

Shaheen, Jack. Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a People. New York: Olive Branch Press. 2001. Print.

Shaheen, Jack. Guilty: Hollywood’s Verdict on Arabs After 9/11. New York: Olive Branch Press. 2013. Print.

Written by Suzanne Harris (2013); edited by Nick Jones (2014), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Selling without prior written consent prohibited. Please obtain permission before redistributing. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2014 Suzanne Harris/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post