Plot New York City, 1970. On the eve of this 40th birthday, Harvey Milk picks up a younger man, Scott Smith and they start a relationship. In 1972, Harvey quits his job moves to San Francisco’s Castro Street to open a camera store. In 1973 he runs for city supervisor but encounters homophobia and fails to secure the gay vote.. Despite assuming a more conservative appearance he also loses the race for a seat on the state assembly. Milk eventually wins a seat on the board of supervisors in 1977 with help from young campaigners Cleve Jones and Anne Kronenberg. Tired of gruelling political campaigns, Smith leaves Harvey, who later starts a relationship with Jack Lira. Milk serves on the board of supervisors, alongside former firefighter and policeman Dan White. The socially conservative White initially cooperates with Milk to their mutual political benefit. Lira becomes increasingly jealous and unstable. Against a national backdrop of challenges to gay rights, California state senator John Briggs attempts to introduce Proposition 6, legislation which would bar homosexuals from the teaching profession. His working relationship with White crumbling, Milk fears defeat on a San Francisco gay-rights ordnance. Milk speaks at a large rally despite a death threat and, supported by Mayor George Moscone, challenges Briggs. Lira hangs himself. Proposition 6 is unexpectedly defeated. White resigns his seat but asks to be reinstated. Moscone refuses. Harvey goes to see Tosca then speaks all night to Smith. The next day, White breaks into City Hall and shoots dead Moscone and Milk. Thirty thousand people take part in a candlelit vigil.

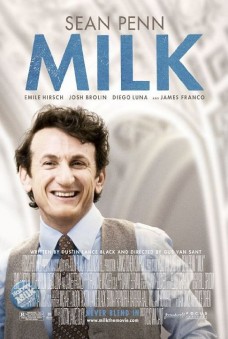

Film Note The development, production and exhibition of Gus Van Sant’s 2008 film Milk illustrates how difficult it can be to get a film into production, even with stars attached to the project. Its classification as a biopic, Van Sant’s connection to Queer Cinema and some contentious issues surrounding its release and distribution bring to light the many obstacles a film dealing openly with gay issues and political subject matter faces.

Creative difficulties Milk went from script to release in less than two years. However, this was not the first Harvey Milk biopic that Gus Van Sant had been connected to. The desire to produce a Harvey Milk biopic can be dated back to 1982 when Randy Shilts, a gay reporter struggling to find work, wrote a biography of Milk entitled The Mayor of Castro Street. Two years later The Times of Harvey Milk (1982), a documentary based on Shilts’ biography, won Rob Epstein the Academy award for Best Documentary Feature. By 1991 Oliver Stone along with Craig Zadan and Neil Meron, the openly gay production team behind Storyline Entertainment, were developing a script based on the book to also be titled The Mayor of Castro Street. Written by David Franzoni in 1992, Gus Van Sant was set to direct and Robin Williams to star, though neither had confirmed. At the time Van Sant spoke of this development phase sarcastically to Entertainment Weekly, revealing an ongoing conflict between himself and Oliver Stone as to who would direct (May 15, 1992). By July 1992 a deal had been made, Van Sant and Williams had confirmed to shoot with Warner Brothers yet Franzoni’s script was still in development. At the end of December 1992 The Inquirer reported that Robin Williams had signed onto a Chris Columbus film, titled ‘Madame Doubtfire’ (Murphy 1992). Production of The Mayor of Castro Street was due to begin in April the following year. Van Sant however was set to complete work on Even Cowgirls Get the Blues creating a clash with the Columbus project. Despite this Williams was still enthusiastic about the role and production was pushed back again until ‘early summer’ of the same year. However in April 1993 Variety reported that Van Sant had left the project due to creative differences over the script. The report suggested that Van Sant was unhappy with the most recent draft of the script, written by Becky Johnston, and had handed in his own treatment to Stone and the other producers. Stone didn’t like the rewrite. Due to this disagreement, Van Sant decided to leave the project (Eller). Two months later, in June 1993, The Reading Eagle reported that Rob Cohen had expressed interest in the project and was reportedly meeting Williams to attempt to confirm his participation. Williams expressed dissatisfaction with the script and left the project in October 1993. The following month Warner Brothers offered Daniel Day-Lewis the part of Milk, with Cohen still at the helm. This offer was declined, along with rumoured other offers to Richard Gere and Al Pacino. The Mayor of Castro Street’s production continued to flounder throughout the 1990s. In an interview in The Advocate in March 1998 Van Sant was asked if the Harvey Milk project was happening and in reply discussed the creative differences over the screenplay, stating his desire to portray Harvey Milk’s gay relationships rather than place emphasis on his career in politics (Hofler). Stone eventually abandoned the project, leaving it with Zadan and Meron who found success with Chicago in 2002. Seven years later director Brian Singer became attached to The Mayor. Around the same time screenwriter Dustin Lance Black was in the process of meeting with Harvey Milk’s associates and contemporaries, with the intent of writing a biopic. When he completed the screenplay in February 2007 he showed it to Cleve Jones, a pioneering gay activist and Milk’s former intern and friend. Jones took it to Gus Van Sant who agreed to direct (Winn). Producers Dan Jinks and Bruce Cohen, who had won an Academy Award for American Beauty (1999), secured finance with Focus Features, the art-house division of Universal pictures, and Groundswell Productions (Garrett). The film began shooting on schedule in California during January 2008 (Goldstein). Sean Penn later won the 2009 Academy Award for Best Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role for his portrayal of Harvey Milk, whilst Dustin Lance Black won Best Writing and Original Screenplay. The development of the abortive earlier biopic illustrates how artistic differences, scheduling conflicts and crowded schedules can affect a film’s production, even before the question of the political nature of the Milk biopic is taken into account.

Hollywood, homosexuality and the biopic Homosexual characters had been prohibited from featuring in films produced under the Hays code. However they began to appear after its relaxation in the 1950s and eventual abolishment in 1968. In the 1990s a film movement emerged that was dubbed New Queer Cinema. The movement sought to appropriate the term ‘queer’ and fight against the positive stereotyping that had dominated cinema’s representation of gay characters. Gus Van Sant cemented his position in this movement with his 1991 film My Own Private Idaho. B. Ruby Rich, a prominent queer theorist, noted that “[w]hat was so striking about the 1990s when I came up with this term ‘Queer Cinema’ […] was a meeting of political engagement and aesthetic invention” (Rich qtd. In Rose). In this respect, and in comparison with My Own Private Idaho, Milk is much less avant-garde. Although the range of representations of homosexuality, as well as the frank depiction of gay sexual relations in Milk seemingly place it in the New Queer Cinema canon, the film is at a formal level extremely conventional”: there is little “aesthetic invention”.

Van Sant’s comments regarding the creative differences on The Mayor of Castro Street screenplay are indicative. Speaking about the discrepancies between the original screenplay and his rewrite Van Sant said, “We just showed the Castro as we know it. Whenever there was the topic of sexuality or there was a scene that involved sex or there was a scene in a bedroom, we didn’t relegate it to ‘This is the one scene’. Sexual innuendo permeates the script. Everything that everybody says has some connection to their sexuality” (Hofler). Van Sant’s comment suggests that Lance Black’s script for Milk was in line with his own. Indeed, the opening scene is an unabashed description of casual gay sex: on the eve of his fortieth birthday, Harvey sees Scott in a subway station; he approaches him and almost immediately propositions him. His manner is somewhat emasculated, he speaks softly and pouts. The men kiss minutes after meeting and then leave together. This vivid representation of gay life is often diluted in contemporary Hollywood films, where a comparatively similar heterosexual situation would not be. Ramin Setoodeh comments that despite the fact that homosexual characters are beginning to appear more often in Hollywood films there is evidence of a return to the “positive stereotyping that the New Queer Cinema movement sought to counter”. For Setoodeh, in films such as The Birdcage (1996), In & Out (1997) and The Object of My Affection (1998) “the gay man was beginning to enter mainstream movies, especially romantic comedies, as a kind of cuddly figure” (Setoodeh 2012). B. Ruby Rich shares this sentiment, noting that the New Queer Cinema is “over”: “It’s a niche market. It’s Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. It’s the worst nightmare of every gay activist from the 1970s and 1980s who said, ‘If you don’t watch out, you’re going to end up with lifestyle, lifestyle lifestyle’ […] There’s nothing formality-breaking going on there” (Rich qtd. in Rose). However, although Milk can be accused of a lack of formal adventurousness it is portrayal of a sexually and politically active gay man can hardly be considered to be simply obsessed with ‘lifestyle’.

A comparison between Milk and Brokeback Mountain (2005), two of the most prominent and successful gay-themed films of the last decade, is instructive. Their presentations of homosexuality appear to lie at opposite ends of the spectrum. Whilst the lovers in Brokeback Mountain must hide their love, in Milk it is flaunted. This distinction is offered by a number of critics as the reason Milk under performed at the box office. Variety’s Pamela McClintock described the reaction of a straight man she witnessed whilst watching Milk: “During every kissing scene, the man squirmed nervously. He certainly seemed to like the movie overall, but as I left the theatre, I couldn’t help but wonder if the ‘Fidget Factor’ is stopping Milk from breaking out at the box office and capturing the mainstream’s heart” (McClintock in Jensen 2009). The consensus, it seems, is that Milk was too explicit in its depiction of homosexuality for the mainstream market and too mainstream in comparison to other New Queer Cinema films for the gay market.

Scott Macaulay writes that “[w]ith ‘truer than fiction’ storylines, rich, Oscar-ready starring roles, and natural marketing hooks, biographical films––or, as they are known in the industry, ‘biopics’ – have been a Hollywood staple since Clement Maurice made Cyrano de Bergerac” (Macaulay). Though the political biopic has been a significant sub-genre (see Sunrise at Campobello (1960), Gandhi (1982), JFK (1991) and so on) Milk signals the genre’s willingness since the 1990s to become more inclusive and explore the life experience of previously marginalised groups (Westwell and Kuhn). In terms of its style, Milk treads the line many biopics do between fact and fiction, by interspersing documentary footage from the 1970s seamlessly into the film. The opening credits sequence, which contextualises the prejudice homosexuals faced at the time, as well as the gay rights movement, precedes the short montage that begins the film. An intertitle reads ‘1978’ and Milk sits alone in his kitchen, tape recording his take on the events of his life to be played in the event of his assassination. Short, humorous clips from his speeches give the viewer an impression of his political persona. The clip that ends this sequence is documentary footage of the press conference given after Milk’s and Mayor Moscone’s deaths, effectively telling the viewer how the film ends. Informing the audience of the central character’s fate at the beginning of the film – a common feature of the biopic –recognises that Milk’s life story is already well-known and to cast the film as tragedy. The next sequence – another beginning – is of an entirely different tone, disrupting linearity by skipping back eight years to the eve of Milk’s 40th birthday when he is still in the closet and working on Wall Street. This in media res beginning (doubled in the case of Milk) gives the opportunity of “beginning the story at the moment just before the subject begins to make his/her mark on the world” (Bingham 5). This is particularly relevant as arguably meeting Scott Smith was the turning point in Milk’s life. The most significant interjection that documentary footage makes is in the closing sequence where, after Milk’s death, the streets of San Francisco are filled with people attending a candlelit vigil. The enormity of the gathering is striking as the camera zooms out to show the seemingly never-ending crowds. This closing shot makes clear the affect the murders had on the community and serves to highlight the tragedy of the story, made no less poignant by the fact that the viewer knows Milk’s fate from the outset.

The union of New Queer Cinema and the biopic has attracted controversy, with accusation of Hollywood ‘straightwashing’ biopics by removing any trace of the suggestion of homosexuality. Michael Jensen observes that “Sunrise at Campobello included Eleanor Roosevelt as a character but left out her rumoured liaisons with women. Lawrence of Arabia eliminated the homosexuality of its hero. Clyde Barrow of Bonnie and Clyde was portrayed as impotent where the real Barrow was bisexual” (2011). Though accused of being somewhat chaste in its portrayal of San Francisco in the 1970s, Milk seemed to have heralded a new era for the accurate depiction of gay characters in biopics. Despite this, Hollywood shows little sign of embracing a more inclusive and unflinching depiction of gay characters and their sex lives. For example, Dustin Lance Black’s screenplay for the Clint Eastwood directed biopic J. Edgar (2011) was subject to much speculation as to whether it would address Hoover’s supposed homosexuality. In the film, Leonardo DiCaprio shares a single kiss with his male partner. In an interview with Next Magazine Black claims that “he was given free rein by the producers and there was no ‘gaying-down’ of the material at any point” (September 14th, 2011). Nevertheless, a more conservative approach seems to remain the default setting.

“Harvey would have opened it in October” Two parallels between the events portrayed in the film and events surrounding the film’s release can be drawn which serve to highlight the way in which contemporary Hollywood operates. In the film, Milk and his associates assist in the successful boycott of Coors beer, motivated by a labour dispute. In return for helping pull Coors from local bars and shops Milk struck a deal with brewery distributors to hire more gay drivers. After the film’s release it was revealed that Alan Stock, the CEO of Cinemark, one of America’s largest chains of multiplex cinemas, had contributed $9,999 to the “Yes on 8” campaign in support of banning same sex marriages in California (Wright 2008). Ironically, the chain stood to profit from showing Milk and a Facebook campaign “No Milk for Cinemark” was launched to organise a boycott their cinemas. As such, Milk’s audiences retained some of the political unruliness of the film’s eponymous central figure. The second parallel to be drawn between Milk’s political activism and the film is between Proposition 6 fought in the film, and Proposition 8 which occurred in California around the time of Milk’s release. Whilst Milk defeated Proposition 6, which would have meant the mandatory firing of homosexual teachers in schools, the film failed to contribute to the countering of Proposition 8, which reversed the California Supreme Court ruling that legalised same-sex marriage. Indeed, the passing of Proposition 8 has been described as “the biggest political setback the American gay rights movement has suffered in years […]” (Lim). Milk was premiered on the 30th anniversary of Milk’s death, three weeks after the passing of Proposition 8, thereby missing the opportunity to shape the debate. This does not mean to say that the film could have changed the vote, but serves to highlight the producers’ desire to distance themselves from gay rights’s activism in order not to alienate the wider audience. When interviewed, Van Sant explained that they didn’t want to align the film with the political issues of the moment in the hope of it having a life beyond the contemporary moment, yet he conceded that if Milk was in charge, he would have had it differently (Bowen).

The political alignment was not the only issue that some commentators took issue with regarding Milk’s release strategy. “Focus Features employed a ‘rolling release’ strategy, starting small and slowly expanding the film to over two hundred theatres through Christmas, where it performed well, if not exceptionally. But the studio deliberately kept the number of theatres low, waiting until the end of January to go wide, so they could capitalise on the publicity from the anticipated Oscar nominations, announced on January 22” (Jensen). This was an attempt to model the release strategy for Brokeback Mountain, also produced by Focus Features. However where Brokeback set box office records in its early December limited release it capitalised on this good press by expanding onto more screens much quicker. Some critics believe that this tentative release strategy and disappointing box office performance could have ruined Milk’s chance of winning Best Picture.

Richard Maltby describes the contemporary Hollywood film as a cultural form that combines elements in an opportunistic fashion in order to pull in the largest possible audience (219). Milk in many ways serves to demonstrate Maltby’s point. The difficulties faced by The Mayor of Castro highlight the important influence of producers, scriptwriters and directors and the synergy they must reach in order to successfully create films. Milk in comparison was able to garner support and hence suffered very little in the way of setbacks during production. Milk attempted to avoid alienating a largely heterosexual mainstream audience by avoiding aesthetic experimentation and any direct engagement with the political issues of the day. This exemplifies the underlying need for films to make money and avoid unnecessary controversy, and demonstrates the effective strategies distribution companies employ surrounding award ceremonies. However, in spite pulling its political punches the film can celebrated for being one of the first high profile biopics about an openly homosexual person and it did go some way to depicting gay life in San Francisco in the 1970s as promiscuous and unruly, thereby securing support from gay viewers.

References

Billington, Alex. “Warner Independent Pictures and Picturehouse Shut Down”. First Showing.net. 8 May 2008. Web. Dec 18 2011.

Bingham, Dennis. Whose Lives Are They Anyway?: The Biopic as Contemporary Film Genre. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2010. Print.

Bowen, Peter. “Mighty Real: Gus Van Sant on Milk”. Filminfocus.com 8 Nov 2012. Web. 17 Dec 2011.

Eller, Claudia. “Van Sant off of ‘Castro St.’”. Variety.com 18 Apr. 1993. Web. 17 Dec. 2011.

Garrett, Diane. (2007), “Van Sant’s ‘Milk’ pours first”. Variety. 18 Nov. 2007. Web. 17 Dec. 2011.

Goldstein, Gregg. “Van Sant closes in on Milk tale”, The Hollywood Reporter.com. 9 Oct 2007. Web. 17 Dec. 2011.

Goldstein, Patrick. “A passion project gets beaten to the punch”. The Boston Globe.com. 11 June 2008. Web. Dec. 17 2011.

Hofler, Robert. “Good Will”. The Advocate. 31 Mar. 1998, pp. 47-54. Print.

Irvine, Lindesay (2006), “Infamous”. The Guardian.com. 24 Oct. 2006. Web. 17 Dec. 2011.

Jensen, Michael. “Why Did “Milk” Go Sour?”. Thebacklot.com. 10 Feb. 2009. Web. 13 Nov. 2011.

Lim, Dennis. “Harvey would have opened it in October”. Slate.com. 26 Nov. 2006. Web. Dec. 17 2011.

Macaulay, Scott. “One Life to Lens: of Milk, Men and Biopics”. Film in Focus.com. 26 Nov. 2008. Web. 6 Jan 2012.

Maltby, Richard. Hollywood Cinema. Malden: Blackwell Publisher, 2003. Print.

Murphy, Ryan. “Robin Williams scoffs at talks he won’t portray Harvey Milk”. Philly.com. 30 Dec. 1992. Web. 17 Dec. 2011.

Rose, Jennie. “The last refuge of democracy: a talk with B. Ruby Rich”. GreenCine.com. 7 May 2004. Web 3 Jan. 2012.

Setoodeh, Ramin (2012). “Why does Hollywood hate gay sex?”. TheDailyBeast.com. Web. 6 Jan. 2012.

Shilts, Randy. The Mayor of Castro Street. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1982. Print.

Westwell, Guy and Kuhn, Annette. ‘Biopic’. Oxford Dictionary of Film Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 32. Print.

Winn, Steven (2008), “Picturing Harvey Milk”. SFGate.com. 30 Jan 2008. Web. 17 Dec 2011.

Wright, John (2008), “Gay filmmaker to protest showing of Milk at Cinemark”. Dallas Voice. 5 Dec. 2008. Web. 4 Jan 2012.

Written by Hannah Mary Farr (2012); edited by Ben Skryme (2014), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2011 Hannah Mary Farr/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post