Plot Present-day Cincinnati. In a close-fought Democratic primary, Mike Morris, the liberal governor of Pennsylvania, has a narrow lead over his rival, Senator Pullman. Behind the scenes, Morris’s chief aide Paul Zara and his press secretary Stephen Meyers are closely watching the figures – as is Pullman’s chief aide Tom Duffy. New York Times reporter Ida Horowicz warns Stephen that his view of Morris may be starry-eyed. While Paul is away trying to win over Senator Thompson of North Carolina, who controls a crucial block of votes, Stephen is invited to a secret meeting by Duffy. Duffy tells Stephen that Thompson has been won over to Pullman’s camp by being promised the job of Secretary of State if Pullman becomes president, and invites Stephen to join their team. Stephen indignantly refuses and tells Paul about their meeting. Paul is furious. Stephen starts an affair with Molly Stearns, an attractive young intern; one night she receives a call from Morris and confesses that she had a one-night stand with him and is now pregnant. Stephen finds money for an abortion by dipping into campaign funds. Ida tells Stephen she knows about his meeting with Duffy. Stephen drives Molly to a clinic, promising to pick her up afterwards. Paul sacks Stephen, saying it was he who tipped off Ida. Stephen goes to Duffy and is told that he’s now tainted goods and no longer useful. Molly, having vainly waited for Stephen, returns to her hotel and takes an overdose. Stephen confronts Morris, claiming he has a compromising note from Molly, and demands that he is given Paul’s job and that Morris does a deal with Thompson. Morris capitulates. Paul is sacked, Thompson endorses Morris, and Stephen takes over as Morris’s campaign manager. (Adapted from Kemp 64)

Film note Set around a Democratic primary that will decide the next presidential candidate, The Ides of March (2011) shows disillusionment and misplaced hope, and echoes a wider dissatisfaction with Barack Obama’s presidency and politics in general. Directed, produced and written by George Clooney, who also plays the corrupt governor, Mike Morris, the film is one of several examples from his oeuvre which result in his being seen as a politically and “publicly engaged film-maker”, comparable with Robert Redford (French). Clooney, who has directed five features, often deals with real historical events, including McCarthyism in Good Night, and Good Luck (2005) and the preservation of artworks in World War II in The Monuments Men (2014). In order to call into question public attitudes towards politicians, The Ides of March evokes any number of political sex scandals of recent years and combines this with imagery reminiscent of Obama’s first presidential campaign. This engagement with topical issues is also seen in the film’s abortion plotline, though as we shall see, the film takes an ambivalent standpoint on this matter. Clooney’s onscreen role as a politician, combined with his off-screen involvement in making the film, contribute to an image of him as a star engaged in current affairs and using his influence to make films of social relevance.

The Star Producer The Ides of March is one of over twenty films produced by George Clooney. His filling of multiple roles in the production of the film, those of actor, producer, director and writer, is characteristic of the long-running practice of certain stars seeking greater involvement behind the camera. It is not uncommon for stars to have their own production companies, thus allowing them to be involved in the development of projects from their conception. Clooney’s own Smokehouse Pictures (which he founded with Grant Heslov in 2006) co-produced The Ides of March along with Exclusive Media, Cross Creek Pictures, Crystal City Entertainment and Leonardo Dicaprio’s production company Appian Way Productions.

Star involvement in production is by no means a new phenomenon; 1919 saw the founding of United Artists by Mary Pickford, Charles Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, D.W. Griffith and William S. Hart, thus allowing them to produce and distribute their own films. As Tino Balio notes, “for the first time ever, motion picture performers acquired complete autonomy over their work, not only in the creative stage of production but also in the exploitation stage of distribution” (153). Star ownership of production companies has since been fairly common; the impetus to start such a company is often the desire for greater creative control or to produce more serious content tackling social or political issues. In 1957 Marlon Brando started his company Pennebaker Productions in order to produce work that “[explores] the themes current in the world today” (Schickel 115). Similarly, Warren Beatty, whose production credits include Reds (1981) and Bulworth (1998), has been praised for not “[making] the ordinary Hollywood fodder and most of what he does is very relevant to the time and very brave” (Younge). This inclination towards filmmaking that could be considered socially relevant or politically inflected can also be seem in Clooney’s output as a producer. Smokehouse produced the documentary Playground (2009), which concerns child sex trade, Argo (2012) which depicts the Iran hostage crisis, and the forthcoming Our Brand is Crisis (2016), a remake of a 2005 documentary about the 2002 Bolivian presidential election.

Smokehouse was not Clooney’s first production company. In 2000, Clooney founded, Section Eight Productions, alongside Stephen Soderbergh (“George Clooney’s Smoke House signs first-look deal with WB”). The company provided a platform for both to develop their own projects as directors, as well as producing the work of others, including Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Eleven (2001), Clooney’s Good Night, and Good Luck (2005) and Stephen Gaghan’s Syriana (2005). The company had a first-look deal with Warner Bros, “promising to make films as cheaply as possible in exchange for minimal creative interference” (McLean). Section Eight was shut down in 2006 in order for Soderbergh to concentrate on directing (McLean), and in the same year Clooney founded his current company Smokehouse Pictures (“George Clooney’s Smoke House […]”). Smokehouse also had a deal with Warner Bros until 2009, when the company signed a “theatrical development and production deal with Sony Pictures Entertainment” (Mitchell). Similarly to Section Eight, Smokehouse produces a mix of films directed by its founders and others, such as Heslov’s The Men Who Stare at Goats (2009), Clooney’s The Ides of March (2011) and Ben Affleck’s Argo (2012).

Running one’s own production company presents the star with many advantages, both financial and creative. The star can select or develop an idea or script of their choosing, allowing them to focus on areas which are of particular interest to them. In the case of The Ides of March, Clooney and Heslov read the original play, Farragut North, and decided to pursue it as a film because “we […] felt like we could take what we were working on and marry it to this play.” (Cornet). A further level of freedom is afforded the star in terms of casting; in this case Clooney cast himself as Governor Mike Morris, a significant part, but not that of the protagonist. While mentioned in the play, Morris does not have an onstage role or any dialogue, thus allowing the writers to develop the character from scratch to suit Clooney. Clooney’s directorial work frequently does not operate as a star vehicle for him as an actor, as he is usually cast in a supporting role, though the potential for this is undoubtedly appealing to some star producers. For example, Will Smith’s Overbrook Entertainment has produced several films featuring Smith in leading roles, including I, Robot (2004), Hitch (2005), I Am Legend (2007) and Hancock (2008).

However, this creative independence is restricted somewhat by the fact that Smokehouse operates as a subsidiary for Sony Pictures Entertainment, a major studio on whom Clooney’s company is reliant for financing and distribution. Janet Wasko notes that such an arrangement makes Smokehouse a “dependent-independent [producer]”: “because of their dependence on the majors for distribution, their ‘independence’ is still relative” (50). In such an arrangement, the studio has some involvement in production, for example Sony initially wanted to retain the play’s original title for the film (Fischer).

Such production deals are becoming less common; while in 2000 the major studios listed 292 deals with producers, by 2009 this figure was 133 (McNary 2012). In 2009, 21 actors had deals with major studios, half the number with deals in 2000 (McNary 2009). This decline suggests a climate less favourable for star producers looking for deals. As one producer notes, “star and director deals take away the resources from pure producers like me. Studios want the relationship but most aren’t productive except for a few like Will Smith” (McNary 2009). Clooney’s work as a producer is consistently profitable; with a budget of $23m, The Ides of March grossed $77.m worldwide. Even The Monuments Men, a critical failure, took $155.1m worldwide (“George Clooney”).

While operating from one’s own production company presents many advantages, notably a greater degree of creative freedom, allowing the star to develop projects with personal significance for them, he or she is not completely independent from major studios. Commercial considerations and finances are thus still important in determining whether or not a star’s project will go into production; as the Ides of March demonstrates any creative freedom is contingent on profitability.

Abortion in Hollywood The most notable difference between The Ides of March and its source text, in terms of plot, is the addition of the abortion plotline. While the narrative strand involving the consequences of Stephen’s (Ryan Gosling) meeting with Tom Duffy forms the main body of Farragut North, Molly’s (Evan Rachel Wood) one-night-stand with Mike Morris and the ensuing pregnancy do not appear. Here the film utilises a trope established in earlier political films (and undoubtedly influenced by real-life scandals, such as the Monica Lewinsky and John Edwards affairs): that of sexual impropriety between older men in positions of authority with young girls. Examples can be seen in Wag the Dog (1998), where the president is said to have made advances towards a Girl Scout in the Oval Office and Primary Colours (1998), where a presidential candidate has an affair with a 17-year-old who becomes pregnant.

In The Ides of March, an intern, Molly, is revealed to have slept with the presidential candidate Mike Morris and is now pregnant. Stephen, his press secretary, takes money from the campaign funds to pay for an abortion. Molly then kills herself. Abortion continues to be a contentious issue in America; in a 2011 poll, 45% of respondents described themselves as “pro-life”, while 51% considered abortion to be “morally wrong” (Saad). Susan Faludi sees Hollywood’s approach to abortion as a facet of the backlash against “portrayals of strong or complex women” in the 1980s, resulting in plots where “the independent woman gets punished” (315). She notes that, “in this sanctimonious climate, abortion becomes a moral litmus test to separate the good women from the bad” (331).

Perhaps in response to this popular feeling and strongly contested debates surrounding the topic, the film is ambivalent in its handling of abortion. At no point is it suggested that Molly should go through with the pregnancy; she is determined to have an abortion from the outset and this is never questioned. In this respect, the film goes against the grain of most Hollywood depictions of unwanted pregnancy; as Kelly Oliver notes “in Hollywood films unwanted pregnancies become wanted and loved babies” (87). However, ultimately, the narrative punishes Molly for her actions: she dies. This corresponds with Oliver’s observation that abortion in film is usually associated with death (89). She remarks that “the number of popular films that deal with the complexities of abortion are few, and most Hollywood films either avoid it altogether or implicitly warn against it” (89). The Ides of March falls into the latter category; in the film abortion is a source of shame that must be kept hidden. The process by which it is arranged is depicted as shady: a note is passed from Stephen to Molly, which he then tears up; they then proceed to discuss the arrangements in a darkened stairwell where he tells her she will need to leave the campaign and to make the appointment from a payphone. The dialogue displays reticence in relation to the topic; the word “abortion” is not used until the confrontation between Stephen and Morris at the end of the film. The conversations between Stephen and Molly revealing her one-night-stand and the plans for the abortion are oblique; the viewer is expected to infer from her remark that “I needed nine hundred bucks” what has happened and what she intends to do. Morris’s interview with Charlie Rose (playing himself) begins with a brief discussion of abortion rights, foreshadowing the events that follow, though again the word itself is not used. The link between abortion and death highlighted by Oliver is also present in the interview; the interviewer follows his question about abortion with another about the death penalty, as the two topics are perceived as related.

While Molly is initially characterised as confident and independent, as the film progresses this changes as more emphasis is placed on her youth, naivety and vulnerability. Her age, twenty, is repeated on several occasions and she refers to herself as “a teenager” at one point. In the eulogy at her funeral, her father calls her “a little girl, trying to make it in a grown-up world, a world where every mistake is magnified”. This preoccupation with her youthfulness serves to heighten the sense that Morris took advantage of her and that behind her façade of independence and quick-wittedness, she was actually an innocent “little girl”. As such, she ceases to be treated as a person and is reduced to a problem to be dealt with; this dehumanisation is seen in an exchange with Stephen, when he tells her that “this situation just can’t be here”, to which she replies “you mean I can’t be here”. Her identity becomes subsumed by her pregnancy and the political implications that it might have.

As a woman “trying to make it” in a man’s world, the film shows that she is doomed to fail. All of the politicians and senior campaign staff depicted are male. The only other named female member of the campaign team, Jill (Hayley Meyers), is an intern who appears at the end of the film as a replacement for Molly. The shot of her delivering coffee to the staff deliberately echoes a sequence at the beginning of the film, where we see Molly carry out the same action. Ben (Max Minghella) asks “are you a Bearcat?”- the same question Stephen posed Molly when they first met. This serves to create a sense of circularity: events repeat themselves and nothing changes, Jill may also become a “victim” who will be sacrificed if she jeopardises the campaign.

The film’s reticence about abortion likely stems from the fact that highly emotive rhetoric is often used in debates on the topic. As Scott H. Ainsworth notes, “in the language surrounding the public debates on abortion, there is little opportunity for subtlety or nuance” with the problematic terms “pro-choice” and “pro-life” presenting a “lack of fine distinctions” (9). In order not to alienate its audience, the film avoids an in-depth consideration of abortion in favour of an ambivalent, though not entirely neutral, representation. While the film does not explicitly condemn Molly for having an abortion, it does portray her as a victim.

“Yes We Can”: Disillusionment with Obama The Ides of March was originally meant to be shot in 2008, but Barack Obama’s election meant that, according to Clooney, “there was such hope, everyone was so happy. It didn’t seem like the time was right to make the movie […] About a year later, everybody got cynical again, and then we thought we could make this film” (“The Ides of March: Production notes” 4). By the time of the film’s release in 2011, Obama had an approval rating of just 40% (Jones). The film engages with this sense of disillusionment with Obama and the Democrats, as well as with politics in general. However, Clooney’s association with Obama, with his being called the “quintessential Obama Era movie star” (Scott and Dargis), problematizes any criticism of the president, rendering it ambiguous.

Parallels between Obama and Morris are drawn through the imagery used in the film. Most notably, the campaign posters promoting Morris, which feature a stencil image of his face and the word “Believe” in bold beneath it, closely resemble the “Hope” poster of Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. Interestingly, the image of Obama used in the posters is adapted from a photograph of him seated next to Clooney at an event raising awareness for the war in Darfur in 2006. Clooney is a vocal backer of Obama, having supported his presidential campaigns in 2008 and 2012 and organising fundraisers for him. In the film, Clooney fills the role of an Obama-type political figure, promising change and hope for those who feel disenfranchised, his real-life associations with the president further cementing these parallels. Stephen’s idealism follows this impetus but turns sour when his character is revealed to be disingenuous and morally corrupt, echoing liberal disappointment with Obama.

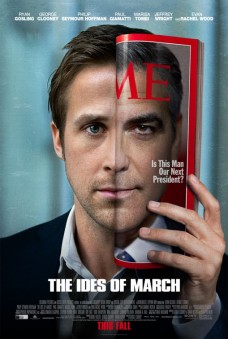

The film’s promotional poster also invites comparison, as the image of Ryan Gosling holding a folded copy of Time Magazine to his face resembles a Time cover from May 2008 featuring half of Obama’s face and half of Hilary Clinton’s.. In the film poster, the tagline “Is this man our next president?” appears next to Clooney’s cheek, while the magazine is folded in such a way that only the ‘ME’ of ‘TIME’ is visible. This suggests a planned usurpation (on the part of Gosling’s character), connotations of which are also evident in the title, The Ides of March, the date of the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44BC, and in the film’s opening scene, in which Stephen delivers Morris’s speech. This speech, which Morris later repeats during a television debate, is also evocative of Obama. In it, he responds to questions about his faith with the assertion that “I am neither a Christian, nor an atheist. I’m not Jewish or Muslim. What I believe, my religion, is written on a piece of paper called the Constitution”. This question of religion is suggestive of those asked of Obama during his first campaign in 2008, when he was frequently required to deny being a Muslim.

In much of the promotion surrounding the film, Clooney is asked about his own political ambitions and whether he would consider a career in politics. In the film’s production notes, producer Brian Oliver is quoted as saying that “George obviously knows the world of politics […] And taking a world that he knows better than most and setting a thriller in that world is a very good fit” (4). Similarly, Ryan Gosling describes him in terms of a political figure: “I think that all of us actors are here because we believe in George, and we believe in his campaign, which is his film” (“Production Notes” 5). This merging of the roles of director and politician creates an ambiguous leadership role filled by Clooney in the film and its promotional material.

If the film is to be read as a criticism of the Obama presidency, then Clooney’s close associations with the president and his public support for his campaigns undermines this criticism. However, the actor has spoken of how he is “disillusioned by the people who are disillusioned by Obama” and feels that “Democrats eat their own” (Marikar); this suggests that the film should be read as a condemnation of those who turn on their leaders when they display weakness. However, this reading is not entirely persuasive and could be more readily applied to a film like Primary Colors (1998). This film presents a similar plot involving a sex scandal which threatens to ruin a presidential campaign. The candidate’s (John Travolta) indiscretion is depicted as a human failing, not impeding his political convictions; he continues to be depicted as a sympathetic character. This is not the case in The Ides of March, where Morris is shown to be calculating and duplicitous.

By the end of the film, the viewer is left with a sense of moral ambiguity: Stephen, has ceased to idolise Morris and is now blackmailing him, while Morris is no longer the morally upright, committed family man he presents himself to be. This lack of distinction between good and bad characters suggests a yearning for political figures offering “change we can believe in” (as promised by Obama), who will not ultimately disappoint. The film implicitly posits Clooney as someone who has seen through these empty promises and has genuine concern for social issues, an appealing potential politician who would deliver change.

References

Ainsworth, Scott H. Abortion Politics in Congress: Strategic Incrementalism and Policy Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010. Print.

Anonymous. “George Clooney.” The Numbers. nd. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

Anonymous. “George Clooney’s Smoke House signs first-look deal with WB”. Monsters and Critics. 18 Mar. 2013. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

Anonymous. “The Ides of March: Production Notes.” Visual Hollywood. nd. Web. 21 Dec. 2014.

Balio, Tino. “Stars in Business: The Founding of United Artists.” The American Film Industry. Ed. Tino Balio. Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1985. 153-72. Print.

Cornet, Roth. “Grant Heslov on ‘The Ides of March’, George Clooney and Politics”. Screen Rant. 3 Aug. 2013. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

Faludi, Susan. “From Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women.” Movies and American Society. Ed. Steven J. Ross. Oxford: Blackwell, 2002. 314-36. Print.

Fischer, Russ. “Sony Picks up George Clooney’s ‘The Ides of March’ for December 2011 release”. Slash Film. 2 Nov. 2010. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

French, Philip. “The Ides of March review”. The Guardian. 30 Oct. 2011. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

Jones, Jeffrey M. “Obama Approval Drops to New Low of 40%.” Gallup. 29 Jul. 2011. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

Kemp, Philip. “The Ides of March: review”, Sight & Sound 21.11 (2011): 64. Print.

Marikar, Sheila. “George Clooney drawn to politics on screen, not in real life.” ABC News. 7 Oct. 2011. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

McLean, Thomas J. “Section Eight goes up in Smoke.” Variety. 12 Oct. 2006. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

McNary, Dave. “Producers’ pacts with majors plunge.” Variety. 12 Sept. 2009. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

McNary, Dave. “Studios cut production deals.” Variety. 27 Oct. 2012. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

Mitchell, Wendy. “Clooney and Heslov’s Smokehouse moves to Sony.” Screen Daily. 1 Jul. 2009. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

Oliver, Kelly. Knock Me Up, Knock Me Down: Images of Pregnancy in Hollywood Films. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012. Print.

Saad, Lydia. “Americans Still Split Along “Pro-Choice”, “Pro-Life” Lines.” Gallup. 23 May. 2011. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

Schickel, Richard. Brando: A Life in Our Times. London, Pavilion Books, 1994. Print.

Scott, A.O. and Manohla Dargis. “Movies in the Age of Obama.” New York Times. 16 Jan. 2013. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

Wasko, Janet. “Financing and Production: Creating the Hollywood Film Commodity.” The Contemporary Hollywood Film Industry. Ed. Paul MacDonald and Janet Wasko. Oxford: Blackwell, 2008. 43-62. Print.

Younge, Gary. “Warren Beatty: Rebel with a Cause.” The Guardian. 23 Jan. 1999. Web. 14 Mar. 2015.

Written by Rosemary Koper (2015), edited by Guy Westwell, Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Selling without prior written consent prohibited. Please obtain permission before redistributing. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2015 Rosemary Koper/Mapping Contemporary Cinema.

Print This Post

Print This Post