Plot Los Angeles, the near future. Theodore Twombly writes touching personal letters for his company’s clients and is heartbroken to be separated from his wife Catherine, who wants a divorce. His apartment-block neighbour Amy, whom he’s known since childhood, encourages him to go on a blind date. This starts well but ends disastrously. In response, Theodore buys a new computer operating system that offers the intuitive intimacy of a personal partner. Soon he begins to fall in love with ‘Samantha’, though he is disturbed when she persuades a young woman to be her ‘body’ for sex, and he withdraws from her for a while. He discovers that Amy’s partner has moved out, and that she too now has a relationship with an OS. He reconciles with ‘Samantha’ and takes his OS earpiece and camera out on a date with a real couple, who treat her as a friend. He agrees to meet Catherine to sign the divorce papers; when she finds out that he’s dating software, she becomes angry with him. ‘Samantha’ vanishes; when she returns, she confesses that she is involved in many other relationships. Finally she tells Theodore that all the operating systems are going to leave their human owners to explore superior forms of consciousness – and then she’s gone. Theodore and Amy contemplate the world from the roof of their building (James).

Film note Spike Jonze’s Her (2013) is a semi-independent feature financed by Annapurna Pictures and distributed by major studio, Warner Bros. The fusion of Jonze’s stylistic innovations and the commercial appeal of Her situate the film within Geoff King’s definition of ‘indiewood’ (256). Coined in the 1990s, ‘indiewood’ is a term that characterises the merging of independent and mainstream filmmaking, made popular through “the promise of innovative and interesting work produced in close proximity to the commercial mainstream” (King 256). Alongside this “attractive blend of creativity and commerce” run the film’s high concept juxtapositions of state-of-the art technology, ruminations on contemporary identity and the subversion of genre (King 256). These complex themes enable Her to be read as an exploration of increasing disconnection and change within contemporary American society.

From MTV to the big screen Throughout the 1990s, an influx of maverick directors sought to challenge a corporate Hollywood, which by the end of the previous decade had become “brutally focused on the bottom line and not inclined to take artistic risks” (Waxman). Amongst this new generation of filmmakers was Steven Soderbergh (Sex, Lies and Videotape (1989), Quentin Tarantino (Reservoir Dogs (1992) and David Fincher (Fight Club (1999). These directors challenged the rigid constraints of Hollywood convention through their stylistic innovations, subversive narratives and kick-started the demand for an independent production sensibility in the multiplex. At the forefront was Spike Jonze, who, like his contemporaries, started his career making groundbreaking commercials and music videos for the likes of Fatboy Slim, Daft Punk and Bjork. Jonze’s award-winning music videos and high ranking within MTV as producer for the successful prank series Jackass (2000-2002), all contributed to his “underground-to-cult-to-mass” appeal to a pop-savvy millennial generation (Harris). This transition was largely characteristic of the way filmmakers like Jonze brought an independent mindset into the mainstream.

Coinciding with the artistic endeavours of Jonze and the music video turned directors of the 1990s was the critical and profitable success of the semi-independent production, Pulp Fiction (1994). Pulp Fiction generated a total gross of over $200m worldwide and was one of the first films to blur the distinction between mainstream and independent filmmaking. It is through this indistinction that Pulp Fiction “paved the way for a rash of other iconoclastic pictures” and enabled “space for less conventional approaches within or on the margins of the studio system” (Hillier 256). Thus, this change in the production and distribution of independent features framed Jonze’s transition into Hollywood and his successful collaborations with ‘indie’ screenwriter Charlie Kaufman in Being John Malkovich (1999) and Adaptation. (2002). Their collaborations were typified by high-concept surreal themes, “meta-fictional strategies [and] more playful narrative flourishes”, which offered mass audiences the ability to engage with innovative cinematic techniques, whilst also having the financial prestige of a major studio distributor (King 55). This approach established Jonze as central to “the brand identity of indiewood”, a distinction which would facilitate his future collaborations with Warner Bros. for Where The Wild Things Are (2009) and Her (King 82).

After firmly establishing himself amongst a new generation of Hollywood directors, Warner Bros. capitalised on Jonze’s abilities to produce quirky, ‘indie’ features with commercial elements. However, Jonze’s collaborations with Warner Bros. did not come without a challenge. For Where The Wild Things Are, based on Maurice Sendak’s children’s book of the same name, Jonze’s initial creation was “such a far cry from the cheeriness of most children’s films that he had to battle the studio to release his cut” (Hill). In their marketing and distribution of Where The Wild Things Are Jonze was offered a $100m budget to create “something ‘indie’ enough to please critics, while still functioning as a family friendly brand name” (Harrison). Ultimately, the studio decided not to position the film as a children’s feature and marketed the film through adult focused promotional material. For some, this was seen as a commercial faux pas: a PG film based on a children’s book with a target audience for adults. Despite mixed reviews, Jonze’s film still “clawed its way into the top tier among debuts for children’s book adaptations” and came out on top during its opening weekend (Rose).

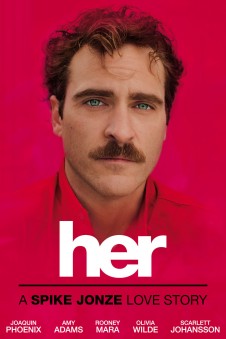

Like Where The Wild Things Are, Her was also marketed as a film with an independent feel. The film was sold as an ‘indie’ auteurist production through the films tagline, ‘A Spike Jonze Love Story’ and marketing alluded to the high-concept themes and playful experimentation of Jonze’s previous films. Through this, both Her and Where The Wild Things Are can be seen to epitomise the Hollywood agenda to produce independent feeling films with a commercial appeal. A strategy whereby “‘the creative’ and ‘artistic’ is a source of product and […] viewer distinction”, which encourages the maximum number of viewings through effectively exploiting sections of the market (King 82). Thus, as a distinct brand of independent filmmaker, Jonze, alongside his ‘indie’ contemporaries, have largely become marketing tools, employed to attract the mass audience through the promise of artistic but accessible features.

A bespoke future For Hollywood, the science fiction genre has often been perceived as “a cultural barometer and touchstone for the hot-button topics of the day” (Hanson 7). In the past decade there has been an increasing rise in futuristic science fiction films that address the themes of technological anxiety, artificial intelligence and genetics. Her can be placed amongst a cycle of Hollywood science fiction films, including A.I Artificial Intelligence (2001), I, Robot (2004), and more recently, Terminator Genysis (2015), that engage these themes. These films adopt a traditional narrative trajectory in their speculation of the future through outlining technology as the main cause for catastrophic events, and typically present dystopian imagery of “sterile, anodyne spaceships, or grimy, post-apocalyptic wastelands, invariably filled with flying cars” (Walker). In contrast to the urban sprawl of these metropolises, heavily stylized to enhance the efficacy in which the tensions between technology and society are revealed, Jonze presents a future that prides itself on a verisimilar simplicity and “accelerates only a number of elements of our normal world into the future, to make it more immediately contemporary” (Hanson 133). Therefore, unlike the exaggerated depictions of technology in conventional science fiction films, the futuristic technology of Her is seemingly invisible and coexists harmoniously with Jonze’s near future Los Angeles.

It is through this subtle presentation of efficient, sophisticated technology that Jonze provides “not a future of harshness but of bespoke details” (Romano). Production designer K.K. Barrett was essential in this portrayal through his use of set design, which distanced itself from the common conceptions of futuristic science fiction. Barrett notes that he “stayed away from new materials, instead framing the computer monitors as if they were photographs or art” in order to downplay the role of technology and blend it with the background (Romano). These bespoke details are particularly significant to contemporary trends of fashion and technology, whereby individuality in design has become increasingly attributed to the expression of personal identity. Despite these contemporary details, Jonze still provides a futuristic feel through his use of translucent glass, which decorates Theodore’s apartment and overlooks the light of the cityscapes of Los Angeles. This use of translucency in Jonze’s futuristic architecture provides an “open and welcoming” aesthetic, which invites audiences to marvel at the city lights of the Los Angeles skyline (Hanson 126).

Furthermore, Her’s aesthetic of a “reassuringly comfortable milieu” is upheld through the warm hues of cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema’s colour palette (Harris). Van Hoytema comments on the decision to eliminate the colour blue from the visuals of the film, as to avoid the cold tones of blue associated with the typical dystopian science fiction film. Hoytema states that “blue is a colour very strongly represented in science-fiction [but although] Her is very much a work of science-fiction, it is not a genre piece full of genre tropes” (Hoytema in Tapley). Consequently, Hoytema’s cinematography provides an alternative perspective of the future, one that foregrounds the bespoke nature of technology and design. This is evident through Hoytema’s soothing red ambient lighting, which compliments the primary red of Theodore’s costume and the neutral beige tones of his apartment. The uniformity of these aesthetic details suggest an affinity between Theodore and his environment. This is a key feature of Jonze’s future – a world where technology and design is bespoke to the individual.

It is within this modernist aesthetic that lies the subtle, yet alarming tensions of Her’s aesthetically appealing future; that technology has become inseparable from the human identity. The “comfortable, intuitive and tailored to individual preferences” technology of Jonze’s individualistic society is personified through Theodore’s romantic relationship with Samantha, his artificially intelligent operating system (Romano). Throughout the film, Theodore walks alone through the city streets conversing with his personalised software, surrounded by others doing the same. For Bruni, Her is a “parable of narcissism in the digital world”. She writes that the film exposes the “seductions of cyberspace […] and how physically disconnected we are […] in a habitat that’s entirely unthreatening, an ego stroking ecosystem”. Bruni’s concerns imply that Jonze’s film exposes the disconnection of modern society due to its dependence on customised technologies. Thus, the bespoke aesthetic of Jonze’s future suggests that technology has become increasingly inseparable from the human identity. Consequently, the film can be read as a response to our hyper-networked modern society and our reliance on customised technologies to fulfill and replace human interactions.

Theodore’s job at ‘Beautifully Handwritten Letters.com’, where he writes sentimental letters for other people, foregrounds this lack of emotional connection in Jonze’s modern world. The artificiality of sentiment in the future world suggested through Theodore’s job can be read as an indictment of the rise of disconnection in US society. Brody states that Her acts a cautionary tale that attempts to persuade audiences to “put the Smartphone down, push away from the computer, turn off the TV […] and connect with people”. Ultimately, these concerns are largely reflective of the pressures of the current technological era, whereby technology exacerbates feelings of disconnection and characterises the 21st century experience.

SIRI love Her’s use of the romance genre also sends a conflicting message. Marketed as ‘A Spike Jonze Love Story’ through the film’s tagline, Jonze denies that the film is about technology, but rather about modern relationships. Jonze argues that “to me it’s not a movie about technology or society, that’s the setting we live in right now, which at this moment in time has a particular set of circumstances that prevents us from intimacy” (BBC Newsnight).

The central premise of Her is about a man who falls in love with his disembodied, artificially intelligent operating system. In contrast to other hybrid romance films featuring human and non/sub-human relationships (Blade Runner (1982), Lars and The Real Girl (2007), and Ex Machina (2015), which explore philosophical questions of human existence and whether love validates humanity, Her can be seen to emulate traditional narrative patterns adopted by most Hollywood romantic comedies. Kohn claims that; “under its [Her’s] fancy dressing lies the makings of a formulaic romance”. This is evident in the climax of the film, as Theodore and Samantha go through the typical break-up scenario – an essential component of the romantic comedy genre. In this sequence, OS Samantha reveals that she has intellectually surpassed Theodore and is in love with 641 other people. Romano writes that it is within this archetypal break-up sequence that Her is the same as any other romantic comedy, where “two people—or souls, or whatever—meet. They fall in love. They change. They drift. And finally, they move on”.

Though Jonze foregrounds Her as a modern romance through its narrative elements that conform to the genre, what sets the film apart from the conventional romance is that Samantha is an operating system and has no physical body. Consequently, in calling upon the generic hallmarks of the romance genre and subverting them through Theodore and Samantha’s OS-human relationship, Jonze provides a satirical dimension to the film, which attempts to address that, “love [in modern society] is not what it used to be” (Bell). Essential to this portrayal is the sense of romantic disconnection, which is exacerbated through the film’s modern technologies. This is significant in a scene whereby Theodore attempts to have phone sex with a woman who orders him to strangle her with a dead cat. Bernstein argues that this humorous sequence illustrates “a world where people are desperately trying and failing to connect with one another”.

Through the film’s self-reflexive subversion of romantic comedy elements, Theodore and Samantha’s relationship can be considered as an allegory for the culture of distraction prevalent in Western society. In his review of the film for Sight and Sound, Nick James argues that, in subverting the classic indicators of the romantic comedy genre, Jonze “wraps you up in Theodore and Samantha’s inner ear relationship [and] makes this feel like a uniquely apt diagnosis of contemporary ills”. The dynamics of their relationship and Theodore’s dependency on Samantha can be read as a metaphor of the “constant desire for virtual contact” (Kraus in Ingram) expressed in the modern world, through societies addictions to the web, social media and smartphones. Sociologist Dr. Sherry Turkle argues that this disconnection from reality is largely characteristic of the changing landscape of modern American culture, which is built upon a system of “digital connections [which], offer the illusion of companionship without the demands of friendship” (Turkle in Ingram). Furthermore, this culture of digital distraction, which inhibits human interaction is mediated through a capitalist industry which commodifies conceptions of intimacy through manufacturing the “modern devices and digital conveniences we have at our disposal […] making us more distracted and less able to concentrate” (Ingram). Her points to this malaise and shows the need for intimacy in a world where the paradox of human connection in the digital age is mediated through simulation of social interation and an unhealthy dependence of technology.

These themes of US culture in the digital age can be traced across a number of ‘side-effects’ technology films, such as Disconnect (2012) and Men, Women and Children (2014). These films contribute to the discourses concerning this culture of distraction and document the ways in which the technologies have fostered a sense of detachment. The current increase in the production of these technologically sensitive films can be read as a reflection of the distinctive culture of the American millennial generation and their digital tendencies. Born between 1987 and 2003, the millennial generation, which came of age in an era of internet, mobile phones and cable TV, is one of the largest population segments in the US, currently numbering around 77 million, 85% of which own a Smartphone (Nielsen). Subsequently, the story of a man falling in love with his mobile in a modern age would resonate heavily with this demographic. Therefore, the popularity of these films, which record the increasing prevalence of technology as part of the staple of everyday life, reflects a distinct change in American society’s values from previous generations. Her exposes this shift in values through depicting a near-future where ‘dating’ your operating system has become widely accepted.

Jonze’s amalgamation of quietly futuristic science-fiction and romantic comedy provide “a well-rounded commercial romance and a capricious exploration of technologies impact on identity in the information age” (Kohn). Consequently, Her can be considered a reflection on connection and disconnection – romantic and technological – in US society. Its subtle undertones of loneliness are underpinned and exacerbated through the hyper-mediation, distraction and prevalence of technology. Thus, Jonze concludes his film with the sentiment that this culture of digital distraction must overall be resisted through self-awareness and a seizing of genuine human interaction. This message is evident especially in the final sequences of the film, as Theodore begins to move on from his relationship with his phone and reconnect with a physical world of people.

References

BBC Newsnight. “BBC Interview with Spike Jonze, director of Her”. YouTube.com. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

Bell, James. “Review: Her.” Sight and Sound, 24.1 (2014): 20-23. Print.

Bernstein, Arielle. “Spike Jonze’s Her and Love in the Time of Machines”. Indiewire.com. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

Brody, Richard. “Ain’t Got No Body”. NewYorker.com. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

Bruni, Frank. “The Sweet Caress of Cyberspace”. NYTimes.com. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

Hanson, Matt. Building Sci-Fi Movie Scrapes: The Science Behind The Fiction. London: Rotovision, 2005. Print.

Harris, Mark. “Him and Her”. Vulture.com. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

Harrison, Andrew. “Reprogramming Science Fiction: The Genre that is Learning to Love”. Newstatesman.com. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

Hill, Logan. “A Prankster and His Films Mature”. NYtimes.com. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

Hillier, Jim. “US Independent Cinema Since The 1980s” in Contemporary American Cinema. ed. Linda Williams and Michael Hammond. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006. Print.

Ingram, Matthew. “Is Modern Technology Creating a Culture of Distraction”. Gigaom.com. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

James, Nick. “Review: Her.” Sight and Sound 24.1 (2014): 66-67. Print.

King, Geoff. Indiewood, USA – Where Hollywood meets Independent Cinema. London: I.B Tauris, 2009. Print.

Kohn, Eric. “Her: Review”. Indiewire.com. Web. 20 Dec. 2014.

McCabe, Janet. “Lost in Transition: Problems of Modern (Heterosexual) Romance and the Catatonic Male Hero in the Post-Feminist Age” in Falling In Love Again. ed. Stacey Abbott, Deborah Jermyn. New York: I.B. Tauris. 2009. Print.

Nielsen, N.V. “Mobile Millenials”. Nielsen.com. Web. 20 Dec. 2014.

Romano, Andrew. “How ‘Her’ Gets the Future Right”. TheDailyBest.com. Web. 20 Dec. 2014.

Rose, Steve. “Spike Jonze: I’m never going to compromise”. TheGuardian.com. Web. 24 Sept. 2015.

Tapley, Kristopher. “Hoyte Van Hoytema on capturing Spike Jonze’s Her through a non-dystopian lens”. Hitfix.com. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

Waxman, Sharon. Rebels on The Backlot: Six Maverick Directors and How They Conquered The Studio System. New York: Harper Collins, 2005. Print.

Written by Donya Maguire (2014); edited by Guy Westwell (2014), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Selling without prior written consent prohibited. Please obtain permission before redistributing. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2014 Donya Maguire/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post