Plot New York City, late 1980s. Jordan Belfort, a middle-class man from Queens, begins his career as a Wall Street stockbroker. After the Black Monday crash of 1987, Belfort loses his job and begins trading near-worthless ‘pink sheet’ penny stocks from a Long Island office. Because of his Wall Street experience and great salesman persona, this new venture proves immensely profitable. Belfort decides to start his own brokerage firm, Stratton Oakmont, aiming to defraud investors wealthier than the usual ‘pink sheet’ clientele. He hires his old neighbourhood friends and current neighbour Donnie Azoff, who becomes his right-hand man. Belfort accumulates immense wealth and re-marries, leaving his wife Teresa for a model called Naomi. He embarks on new, more audacious scams, including helping the Steve Madden shoe company, the majority of which he owns via proxy, to go public. Learning that he has attracted the unwanted attention of business regulators, Belfort begins to stash money away in a Swiss bank account. After his yacht sinks in a last-ditch effort to retrieve the money, Belfort quits trading but is ultimately jailed for his transgressions. Naomi files for divorce and custody of their two children. When we last see him, he is working as a motivational speaker in New Zealand (adapted from Pinkerton 92).

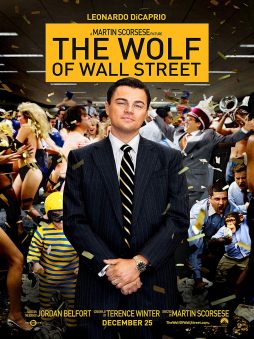

Film note With worldwide box-office takings of $392m, The Wolf of Wall Street is Martin Scorsese’s most commercially successful film to date. The dark comedy-drama won 36 of its 155 award nominations and was listed as one of the American Film Institute’s top ten films of the year. The project was co-produced by Appian Way, a production company Leonardo DiCaprio created “to find material outside of the studio system” (“Leonardo DiCaprio Talks”). The film’s explicit content and portrayal of morally reprehensible characters and actions caused difficulties in terms of financing and distribution while simultaneously contributing to the film’s success.

Sex, drugs and… five Academy Award nominations Although the filming of The Wolf of Wall Street began in August 2012, Leonardo DiCaprio had been interested in the project since 2007. Captivated by Jordan Belfort’s memoir, DiCaprio was determined to buy the rights to the book, entering and eventually winning a bidding war against fellow actor-producer Brad Pitt. It took five years for the book to be adapted, as all of the big studios were discouraged by the story and its explicit sex and drug content which was guaranteed to demand calls for censorship. DiCaprio’s project therefore struggled to secure financing and initially stalled. In 2010, Warner Bros offered to produce the film with DiCaprio playing the lead role and Ridley Scott as the director, but they soon abandoned the project completely due to the film not fitting well with Warner Bros’ current slate. At the time, the studio was better known for focusing on ‘family entertainment’ such as the Harry Potter film franchise (2001-2011).

The film was then picked up and financed by Red Granite Pictures. Terence Winter’s screenplay convinced Red Granite CEOs, Riza Aziz and Joey McFarland, to accept the challenge of producing a film with such explicit content and a large budget of $100m. Importantly, against the usual Hollywood process of financing having the power to “restrict and limit creativity” the creators of The Wolf of Wall Street had almost complete artistic freedom (Kuhn & Westwell 408). Winter stated that the aim of the creatives involved in the making of the film was “to tell the truest version of this story and not the sanitized version” (Galloway). Amusingly, the real Belfort admitted that some of his experiences were even more outrageous than those depicted by the film (“Leo Recounts”). However, Scorsese had to be careful in order to secure a reasonable rating from the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America). He removed scenes containing excessive nudity and sexual content in order to avoid the most explicit NC-17 rating, which would not allow anyone under the age of seventeen to watch the film, even with adult supervision (McClintock). In the end, the MPAA gave the film an R rating, one below NC-17, “for sequences of strong sexual content, graphic nudity, drug use and language throughout, and for some violence. The film also holds the Guinness World Record for the most expletives said in a mainstream non-documentary film, the word “fuck” being said a total of 506 times (Thorne). Whilst the MPAA gave the film what could be seen as a lenient rating, it is completely banned in four countries – Nepal, Zimbabwe, Kenya and Malaysia (the home country of Red Granite’s CEO, Riza Aziz). Other countries have also insisted that up to forty-five minutes of scenes involving sex and drugs be cut.

Despite pushing the boundaries of Hollywood film censorship, The Wolf of Wall Street received five nominations at the 86th Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Actor (for DiCaprio) and Best Supporting Actor (for Hill). Although the film did not win any Academy Awards, it can be argued that receiving five nominations was a tremendous success for such an explicit and boundary-pushing film. It also won two Golden Globes – Best Comedy and Best Actor (for DiCaprio). This, alongside the film’s financial success, supports DiCaprio’s statement that “there was a marketplace for films like this” (“Academy Conversations”). It is clear that the film, and especially the very explicit content that initially halted its production, struck a chord with audiences worldwide.

‘More is never enough’ The central themes of wealth, power and desire to succeed in The Wolf of Wall Street align with the ideal of the ‘American Dream’, understood as the “freedom to pursue happiness without socio-economic class barriers” (Benshoff and Griffin 167). Denying the preconditions of the socio-economic class system, the American Dream promises that with ambition, hard work and determination, all Americans can become rich and economically successful. The film offers Belfort as an ambiguous symbol of the American Dream, in a version of it in which the aim is to accumulate wealth and improve one’s financial status regardless of the consequences this may have on others. As he explains in his narration and opening introduction, Belfort came from a middle-class background and, through hard work and determination, has made his way up the financial ladder to become the founder and CEO of his successful yet amoral brokerage firm, Stratton Oakmont.

The film begins with a TV commercial for Stratton Oakmont. It presents the company as reliable and trustworthy by using trigger words such as “stability” and “integrity,” suggesting that the firm holds strong moral values and is honest with customers. The scene in the calm, lavish office immediately cuts to an image that completely juxtaposes the advert. The same office is now crowded with rowdy stockbrokers who are gathered around a large target, shouting aggressively and waving large wads of cash. Suddenly, a dwarf is thrown at the target, an image so outrageous it is bound to produce a comedic effect. Clint Burnham states that this contrasting cut highlights “what Wall Street is really about, […] not those respectable, honest, suit-clad brokers helping you make money,” but a swarm of greedy degenerates (130).

As the head of the company, Belfort gives numerous motivational speeches to his stockbrokers, encouraging them to have no regard for others and adopt the ‘work hard, play hard’ ethic he so values. One such speech occurs right before Steve Madden’s stock is released for sale to the public. Belfort urges his employees to sell the stock as though their lives depended on it. He addresses them in an aggressive and almost animalistic way, referring to them as his “killers,” evoking the image of bloodthirsty carnivores. Belfort looks insane, repeatedly hitting his head with the microphone, his facial expression deranged, eyes wide and jaw pushed forward in a beastly, wolfish fashion. “There is no nobility in poverty,” he exclaims, referencing Wall Street (1987), a film about a power-hungry young man determined to make it to the top of the American finance industry. Coincidentally, the real Belfort has admitted that the character of Gordon Gekko, the mentor figure in Wall Street, inspired his ‘get-rich-quick-by-any-means’ attitude (Leonard). Belfort proceeds to remind his audience of his humble beginnings; when comparing being poor to being rich, he exclaims “I choose rich every fucking time.” The crowd erupts in supportive cheers; they see Belfort as a godly figure, completely mesmerized by his performance and words. They applaud nearly every sentence, brainwashed into believing that this kind of work ethic is the only way forward. Belfort and his loyal followers are shown by the film to be deluded in their self-entitlement and greed and thereby lead the audience to question the ethos of the American Dream. Belfort describes the company as “the land of opportunity,” but it could be said that “the American dream has evolved from the land of opportunity to the land of entitlement” (Kuo). That said, the film’s positioning of the audience is not completely clear cut.

Due to the rapid changes occurring in the corporate world, the 1980s offered the prospect of a “fast-forward version of the American Dream,” thus facilitating white-collar crime (Fraser 121). This economic climate accentuated the kind of greed that, according to DiCaprio, Scorsese and Winter, is within human nature (“Leonardo DiCaprio, Martin Scorsese Reveal Secrets”). But rather than present this in a morally straightforward way, with the audience clearly positioned to negatively judge the behaviour of Belfort and his team, the film seeks a more complex dialetic. Burnham notes that “two contradictory propositions come to mind. The first is that the film is a celebration of Wall Street, of the stockbroker lifestyle: fast cars, big houses, hookers, and blow […] the second is the opposite proposition: the film shows how stupid Belfort and his crew are, how excessive their pleasures, and punishes them for that excess” (96).

The film is celebrated for using “every technique in the cinematic palette” (Morrow), as the fast-paced, in-your-face editing and brightly coloured and exuberant aesthetic of the film mirrors Belfort’s eccentric lifestyle. Some view this extravagant portrayal of Belfort’s experience as a dangerously desirable representation of greed, wealth and power which could “inspire a fresh crop of degenerates to ignore its potential cautionary power and embrace the lifestyle it represents” (Chang, Debruge & Foundas). The film certainly concentrates on the wealth and hedonism of the “winners” more so than the lives of the victims of Belfort’s penny stock scams or the “stiffs” who are, as he phrases, “swallowed up and shit right back out” by Wall Street. However, Scorsese and DiCaprio, as well as the real Jordan Belfort, are quick to deny such claims, with the latter stating “it’s laughable when people say [Scorsese] is glorifying my behaviour, because the movie is so obviously an indictment. I could have easily been redeemed at the end of the film, because I am redeemed in real life, but [Scorsese] left all that out because he wanted to make a statement” (qtd. in Lewis). While this sentiment is valid – the film could be said to ridicule Belfort’s decadent lifestyle – it is nevertheless important to note that Belfort is constructed as a likeable, or, at the very least, alluring, character, thus complicating the film’s cautionary aspect. The fact that it is difficult to identify whether the film is celebration or satire suggests that both possibilities are intended, and, indeed, held in balance, leaving the viewer to make their own interpretation.

Breaking the fourth wall: rooting for the bad guy In an interview with Entertainment Tonight, DiCaprio spoke of a discussion he had with Scorsese regarding whether audiences would identify with an “incredibly self-indulgent and narcissistic” character. He recounted Scorsese’s advice that “as long you’re authentic in your portrayal of who these people are, you don’t try to sugar-coat it and you don’t try to give a false sense of empathy or sympathy for them, if you’re honest, audiences will go with you” (“Leo Recounts ‘Wolf of Wall Street’ Debauchery”).

It is worth noting that Scorsese is known for directing crime/gangster films, notably Goodfellas (1990), which tells the story of the rise and fall of a gangster in New York during the 1980s. There are clear similarities between Goodfellas and The Wolf of Wall Street, as they both employ voice-over narration and follow a character intent on having a wealthy lifestyle and powerful status by any means necessary. Carl Javier describes Belfort as “a twisted, compelling new main character who is both despicable and incredibly irresistible”; he is exposed as a criminal guilty of fraud and money laundering. In this sense, Belfort is the leader of a gang (Stratton Oakmont) and his fellow gangsters (stockbrokers) participate in organized crime by knowingly scamming naïve investors. As Burnham puts it, “finance capitalism is gangsterism in the sense that it is a violent system that encourages impossible economic dreams instead of actual social change, a system that sets up the accumulation of profit from the buying and selling of stocks” (118). This highlights the influence of Scorsese’s auteur style on the film and brings about the question of whether a deceitful and power-crazed white-collar gangster can be constructed as a likeable protagonist.

Whilst discussing the film with The Hollywood Reporter, Terence Winter revealed that he and Scorsese agreed that he would write the screenplay of The Wolf of Wall Street in the style of Goodfellas and Casino (1995) (Galloway), the use of voice-over narration being a distinguishable element of Scorsese’s auteur style. Belfort’s narration gives the film’s events a sense of authenticity and realism and may result in audiences empathising with a morally reprehensible protagonist. Ashley Clark suggests that direct address is “a startling concession that dislodges viewers from their comfort zone and is guaranteed to provoke a reaction. It’s a trick that can be used to distance or compel; it can be funny, shocking, irritating or even patronising”. Introducing such an element can therefore shift the audience’s feelings towards an otherwise reprehensible character. This technique is used successfully in films such as Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986), Fight Club (1999) and the Alfie films (1966, 2004), all of which employ voice-over narration in order to lead the spectator to side with their anti-heroes.

In The Wolf of Wall Street, the use of direct address and voice-over narration aids the creation of a compelling, if not wholly likeable, character through evoking comedy, authority, authenticity and intimacy. The use of direct address during Belfort’s opening monologue certainly adds to the comedic value of the scene, unsurprisingly, as this is a technique often employed in the comedy genre (Brown 41). Belfort candidly admits to his eccentric, often illegal activities in statements such as “on a daily basis I consume enough drugs to sedate Manhattan, Long Island and Queens, for a month.” His openness is so ludicrous it becomes amusing despite the subject matter. Anne Van Der Klift argues that “comedy effects, aided by music and Belfort’s voice-over, diminish the immorality of his actions” (43), therefore validating the use of comedic direct address to render Belfort more likeable. Furthermore, this often-comedic element also adds to the “patronising” (Clark) authority of Belfort’s character. This is seen in the film when Belfort stops explaining the term IPO to the spectator, saying “look, I know you’re not following what I’m saying anyway, right?,” thus undermining his likeability while re-establishing his authority, which contributes to the compelling aspect of his character. Belfort’s comedic, patronising openness also provides the kind of authenticity valued by Scorsese (“Leo Recounts ‘Wolf of Wall Street’ Debauchery”). This gives the film an intimate dimension, as the audience feel like they know Belfort better than any other character in the film. He discloses every minute detail to the camera, positioning the audience as his confessor. To take this further, Burnham suggests that breaking the fourth wall renders the film “immersive,” as it “makes us uncertain about our own identity” (134), forcing us to position ourselves with regards to the film world. Belfort’s insight, presented through direct address, adds to the film’s unique charm and character and forces the audience to accept and root for him through achieving a sense of intimacy.

Finally, another important factor contributing to Belfort’s potential likeability is “DiCaprio’s charisma and the sympathy the spectator might have for this actor,” perhaps leading us “to keep looking for reasons to sympathize with Belfort” (Van Der Klift 43). The use of direct address, aided by DiCaprio’s presence, contributes to the film’s compelling effect and renders Belfort a more likeable character than one would expect based on his status as a greedy criminal adulterer with a colossal drug addiction. It is indeed possible that the casting alone makes Belfort a likeable character; DiCaprio is a famous heartthrob and a critically acclaimed actor, also known for his philanthropy and environmental activism. The marketplace positioning of The Wolf of Wall Street therefore benefits not only from Scorsese’s auteur status, but also from DiCaprio’s stardom. The film’s success despite its initial struggle to find a studio willing to take a risk on such an explicit story points to DiCaprio, Scorsese and Winter’s ability to engage an audience in complex ways with their portrayal of a debased, corrupted American dream.

References

“Academy Conversations: The Wolf of Wall Street.” YouTube. 3 Jan. 2014. Web. 8 Mar. 2020.

Benshoff, Harry M. & Griffin, Sean. US on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender and Sexuality at the Movies. New Jersey, Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Print.

Brown, Tom. Breaking the Fourth Wall: Direct Address in The Cinema. Edinburgh University Press, 2013. Print.

Burnham, Clint. Fredric Jameson and The Wolf of Wall Street. London, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016. Print.

Chang, Justin, Debruge, Peter, Foundas, Scott. “3View: Taking Stock of ‘The Wolf of Wall Street’.” Variety. Web. 23 Dec. 2013. Accessed 29Oct. 2016.

Clark, Ashley. “Clip Joint: Breaking the Fourth Wall.” The Guardian. Web. 9 Nov. 2011. Accessed 14 Dec. 2016.

Fraser, J. A. White-collar Sweatshop: The Deterioration of Work and Its Rewards in Corporate America. New York, Norton, 2001.

Galloway, Stephen. “Martin Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio Finally Open Up About ‘Wolf of Wall Street’.” The Hollywood Reporter. 4 Dec. 2013. Web. 8 Mar. 2020.

Javier, Carljoe (2014), “Movie Review: The Wolf of Wall Street’ Explores a Different American Dream.” WHERE? 17 Jan. 2014. Web. 20 Nov. 2016.

Kuhn, Annette & Westwell, Guy. A Dictionary of Film Studies. Oxford University Press, 2012. Print.

Kuo, Kendrick. “The Wolf of Wall Street and The New American Dream.” Patheos. 25 Dec. 2013. Web. 20 Nov. 2016.

Leonard, Tom. “The Wolf of Wall Street: Meet the Real Bad Guy.” The Telegraph. 9 Jan. 2014. Web. 9 Mar. 2020.

“Leo Recounts ‘Wolf of Wall Street’ Debauchery.” YouTube, uploaded by Entertainment Tonight, 17 Dec 2013. Accessed 8 March 2020.

“Leonardo DiCaprio, Martin Scorsese Reveal Secrets of Making ‘The Wolf of Wall Street’,” YouTube, uploaded by The Hollywood Reporter, 10 Dec. 2013. Accessed 8 Nov. 2016.

“Leonardo DiCaprio Talks Wolf of Wall Street in the Golden Globes Press Room.” YouTube, uploaded by POPSUGAR Entertainment, 14 Jan. 2014. Web. 8 Mar. 2020.

Lewis, Hilary. “Oscars: ‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ Shut Out.” The Hollywood Reporter. Web. 2 March 2014. Accessed 15 Dec. 2016.

McClintock, Pamela. “Wolf of Wall Street Avoids NC-17 After Sex Cuts.” The Hollywood Reporter. Web. 27 Nov. 2013. Accessed 16 Dec. 2016.

Morrow, Justin. “A Look at the Influential Editing Techniques of Martin Scorsese & Thelma Schoonmaker.” No Film School. Web. 28 Aug. 2014. Accessed 8 March 2020.

Pinkerton, Nick. “The Wolf of Wall Street.‘’ Sight and Sound, 24.2 (2014): 92.

Thorne, Dan. “How The Wolf of Wall Street Broke Movie Swearing Record.” Guinness World Records. Web. 16 Jan 2014. Accessed 16 Dec. 2016.

Van Der Klift, Anne. Rooting for the Morally Questionable Protagonist. MA Thesis. University of Amsterdam, 2014. Web. Accessed 9 March 2020.

Written by Mikaela Wood (2017); edited by Maria Majewska (2020), Queen Mary, University of London.

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2020 Mikaela Wood/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post