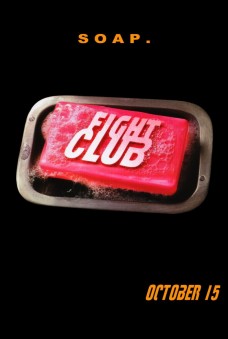

Plot The present. The narrator, possibly named Jack, has a gun in his mouth in a building about to be blown up. Months before, Jack lives in an unnamed US city, has a good job and a trendy flat, but feels empty and can’t sleep. Jack follows his doctor’s flip suggestion that he attend a testicular-cancer support group to find out “what real pain is”. Moved to tears by the members’ plights, Jack’s insomnia is cured and he becomes hooked on group therapy. Soon he notices Marla, another “tourist”, and his sleeplessness returns until they agree not to attend the same groups. On a plane, Jack meets Tyler Durden, who makes a living selling soap. When Jack’s flat mysteriously blows up, Tyler offers him a place to stay, but only if Jack will hit him. Tyler and Jack beat each other up for fun. They start Fight Club, at which men can fight each other. Marla calls Jack after taking an overdose: Tyler comes to her rescue and they begin a sexual relationship, much to Jack’s disgust. Meanwhile, Fight Clubs spring up all over the country. Tyler starts Project Mayhem, which involves acts of terrorism against corporations and big business. During one mission Mayhem-soldier Bob is killed. Jack is horrified; Tyler disappears. Jack criss-crosses the country in search of him, only to find everyone thinks he is Tyler. Realising they’re right, Jack tries to foil Tyler’s plans to blow up several high-rise buildings (credit card companies) at once, but is thwarted. At the primed-to-explode building seen in the opening sequence, Jack shoots himself in the head, only wounding his real body but “killing” Tyler. Marla, whom he’d put on a bus to safety, is brought to him and they watch together as the bombs go off.

Film note Fight Club was released during a particularly successful period for its parent company 20th Century Fox. The re-release of the first Star Wars trilogy in over 2000 cinemas in 1997 grossed $250m and the release of the first Star Wars prequel, The Phantom Menace (1999), had fans queuing outside cinemas for two days. Most astonishing of all, however, was the spectacular success of Titanic (1998). Fox had parlayed $140m of the film’s $200m budget after co-financiers Paramount capped their investment at $60 million. Although Fox could easily have faced financial disaster, instead they ended up controlling a major stake in the highest grossing film in cinema history.

21st Century Fox As well as reaping the dividends of staple blockbuster fare, this period also saw Fox displaying a willingness to invest in alternative projects. Michael Allen notes that “Lindsay Law, president of Fox Searchlight, which is owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation, told the New York Times that he had been given complete autonomy and had been told by executives at Twentieth Century Fox, the parent company, to tackle any subject. ‘The instructions are not to be afraid,’ Mr Law said” (172). Consequently, Fox produced two of the most politically provocative (studio) movies of the late 1990s: veteran upstart Warren Beatty’s Bulworth (1998) and Fight Club (1999), an adaptation of Chuck Palahniuk’s debut novel directed by the 34-year-old David Fincher.

A flashback to the early part of the decade can help explain this willingness to take risks. The US film industry was hit hard by the economic recession of the early 1990s. Video and TV revenues flattened out and between 1990 and 1991 an eight per cent drop in cinema admissions was reported (Allen 44). Hollywood responded by seeking to expand its share of foreign markets and by acquiring the talent and acumen of successful independent distributors: in 1993 Disney bought Miramax while the Turner Broadcasting Corporation merged with New Line and was absorbed into the Time Warner conglomerate. The upshot of this was the production and promotion of relatively low-budget “left field” projects such as Miramax’s Pulp Fiction (1994) and New Line’s Se7en (1995), the success of which would impact profoundly on (bigger budget) Hollywood output of the mid- to late-1990s.

Liner notes for the Fight Club DVD describe how Kevin McCormick, the former Executive Vice President of Production at Fox, brought in producers from Atman Entertainment to help him “convince Laura Ziskin [President of Production at Fox] to buy [the rights to Palahniuk’s novel]”. Jim Uhls, the film’s screenwriter, states in the same notes that Ziskin made the deal for the book, for David Fincher and for his own services despite the fact that within the industry the film was “generally thought to be problematic for adaptation”. Fincher had established himself in the early 1990s as a pop-promo and TV-ad wunderkind, but his directorial debut feature film Alien 3 (1992) had resulted in disappointing returns for Fox. However, the thriller Se7en (1995) was both a critical and box-office hit, raising the director’s profile and rendering him a credible contender for the Fight Club job. Speaking to Sight & Sound at the time of the film’s release, Fincher described how obliging the studio had been: “From the script we put together a schedule, storyboards [and] a budget. I went back to Fox with an unabridged-dictionary sized package. I said, ‘Here’s the thing. $60m. It’s Edward [Norton]. It’s Brad [Pitt]. We’re going to start in Edward’s brain and pull out. We’re going to blow up a fucking plane. You’ve got 72 hours to tell us if you’re interested’. And they said, ‘Yeah, let’s go.’”(qtd. in Taubin 18).

However, despite the bankability of any project in development in the late 1990s that had secured Pitt and (twice Academy Award nominated) Norton for its leads, Fox clearly had concerns about whether it could secure an R rating for its treatment of Palahniuk’s explicitly violent and sexual material. Evidence of commercial compromise can be found: for example, on page 59 of the novel are the (narrated) lines: “Tyler and Marla had sex about ten times […] Marla said she wanted to have Tyler’s abortion”. On page 160 the line is reprised: Marla says, “I said I wanted to have your abortion”. The repetition of the line underlines the importance Palahniuk attaches to it. But, even though anti-abortion lobbyists/the religious right were less active in the 1990s than in the preceding decade there was no way this line could feature in the movie. Similarly, the depiction of sex (which takes place mostly off screen) is rendered abstract and “arty” in a series of phantasmagorical shots filmed at different film speeds.

Some of the riskiness of the project was also offset through a careful positioning of the film in the marketplace. This positioning is made clear in the UK territory exhibitor’s marketing document that advises that the film’s target audience is an “extreme male skew”. Under the heading “target audience” the marketing document plays on the film’s tagline to playfully turn female exclusion into a positive: “First rule of FIGHT CLUB–Do not target females; Second rule of FIGHT CLUB–Do not target females.” The same document also invites exhibitors to “use our 18 cert. trailer which you cannot play in your cinema for your internet site”. Notwithstanding this “narrowcasting” strategy, the Fight Club press pack also draws attention to the fact that Brad Pitt, whose previous film Meet Joe Black (1998) had been described as “a world class chick-flick that rests […] on Pitt’s golden shoulders”, and whose real-life relationship with Jennifer Aniston was the subject of much media scrutiny, was arguably the most popular female-audience draw working in Hollywood at the time of Fight Club’s release. This factor, coupled with the so-called “Peter Pan Syndrome”–a principle originating in the late 1960s that claims “[teenage] girls would watch anything boys would watch, but not vice versa”–might suggest that the female demographic was not completely discounted (Maltby 10).

Left-liberal confusion Richard Maltby suggests that social problem/political films “flourish best in a liberal climate” (385), so it is perhaps unsurprising that during the ostensibly liberal 1990s a number of urban political movies appeared. The therapeutic narratives of Grand Canyon (1992) and Magnolia (1999) bookend the decade but an altogether more edgy and satirical sub-genre also emerged in the shape of Falling Down (1993), Fight Club and American Psycho (2000). Writing in Sight and Sound, Amy Taubin states that “Like the novel, the film […] expresses some pretty subversive, right-on-the-zeitgeist-ideas about masculinity and our name-brand bottom-line society–ideas you’re unlikely to find so openly broadcast in any other Hollywood movie” (18). In contrast, Henry A. Giroux and Imre Szeman suggest that in spite of the “onslaught of reviews that celebrated [Fight Club] as a particularly daring example of social critique […]”, the film is simply one of “a new sub-genre of film narratives that combines a fascination with the spectacle of violence [with] tired narratives about the crisis of masculinity [and] a superficial gesture toward social critique” (qtd. in Lewis 95-99). A number of elements in the film indicate that Giroux and Szeman’s identification of superficiality in relation to political issues might be appropriate.

First, Jack’s articulation of his existential ennui is predicated, ostensibly at least, upon the putatively alienating effects of the cultural hegemony dictated by “the Microsoft Galaxy” and “Planet Starbucks” that has rendered him “a slave to the IKEA nesting instinct”. But this double-negative product-placement and referencing/reinforcing can’t have hurt the corporations invoked at all. Indeed, the ”ABC1” demographic who are targeted in the UK marketing plan must have been incredulous upon learning that in America you can order IKEA furniture over the phone! When Tyler tells Jack: “Murder, crime, poverty–these things don’t concern me”, he could easily be talking about the movie. As Giroux and Szeman point out: “Fight Club ignores issues surrounding the break up of labor unions, the slashing of the US workforce, extensive plant closings, downsizing, outsourcing, the elimination of the welfare state, the attack on people of color, and the growing disparities between the rich and the poor” (qtd. in Lewis 99). Instead, a political posturing is adopted, constituted as a play with the signifiers of consumer society.

Second, claims that the film offers a substantive critique of masculinity do not hold water. Alexandra Juhasz argues that Fight Club is “decidedly feminist in the sense that [it is] aggressively self-conscious (and self-confident) about the mobility of gender” (qtd. in Lewis 211). This mobility is signalled, it is claimed, through an acknowledgement that Jack/Tyler are having a homosexual relationship. In fact, a close reading of the film reveals very little to back up Juhasz’s statement that “Jack’s homosexuality [is] virtually explicit”. There are tropes that might be read as sexual metaphors (“the postcoital/post-fight smoke” etc.) but the homosexuality that is inferred in the book is toned down in the film. In the book Tyler is introduced on “a nude beach […] naked and sweating” (32) and Jack summarises the scenario as: “We have a sort of triangle thing going on here. I want Tyler. Tyler wants Marla. Marla wants me” (14). Any homoeroticism suggested in the film between Jack and Tyler is undercut by the revelation that Jack is actually in love with his own “hyper-masculine-heterosexual-fantasy-self. Bill Clinton’s climb-down on his stated intention of passing legislation “…to allow professed homosexuals in the military” (Tindall and Shi 1284) is indicative of the sway that right-wing conservative lobby groups continued to hold in the 1990s. As such, it is hardly surprising that the theme of homosexuality was deemed not a commercially viable theme for a big-budget studio movie that targeted a mostly heterosexual male audience.

Third, in spite of a self-conscious examination of male ego/narcissism, the film maintains a fairly reductive view of women. Juhasz makes the claim that Marla is the one character in Fight Club who is in possession of “the phallus” on the grounds that she uses a dildo (qtd. in Lewis 212). But Marla is almost as schizophrenic as the film’s male(s): a suicidal self-harmer who is an amalgam of the self-obsessive depressive detailed in Elizabeth Wurtzel’s bestselling autobiographical Prozac Nation (1995) and all the other “bad girls” celebrated in her 1998 follow up, Bitch.

Palahniuk states that while he was writing his novel: “The longing for fathers was a theme I heard a lot. The resentment of lifestyle standards imposed by advertising was another.” Accordingly, Fight Club (the book and the film) conflates these issues and presents them as a pathological cultural affliction. The film starts with the camera “pulling out” of Jack’s brain, but in fact, it never really leaves it. When Jack and Tyler chat about their fathers, they are, of course, discussing the same man. Jack says he hardly knows his dad. Tyler does, though, and externalises Jack’s hitherto internalised hatred. Historians George Tindall and David Shi note that “[t]he decline of the traditional [American] family […] continued during the 1980s [and that] the number of single mothers increased by 35 per cent over the decade” (1270). Jack/Tyler is/are thus presented as a contemporary paradigm of the “generation of men raised by women”. Hatred of the absent-father, displaced or otherwise, is matched by a hatred of women. Tyler adds to the line quoted above: “I’m wondering if another woman is really what we need”. And Tyler’s description of Marla as a “predator posing as a house pet” may sound less vicious than the book’s: “Marla is some twisted bitch” (59), but is actually more insidious, suggesting that in the 1990s socially useless women prey on unsuspecting men. This construction of gender relations– a nostalgic longing for a strong patriarch and a fear of emasculating women–is consonant with those that Andrew Britton attributes to the Reaganite movies of the 1980s where “deep male intimacy [of a Platonic nature] blossoms” in the absence of women (24). Something reinforced by the “extreme male skew” of the film’s marketing strategy.

Fight Club was mistakenly claimed to be a clever political film: anti-consumerist, tuned to new, flexible forms of masculinity, and adopting a form of pos feminism. Yet, the close examination presented above indicates that its narrative is dependent on consumerist signifiers for its dramatic charge, a normative heterosexuality is maintained throughout, and the central female character is treated prejudically. These are significant blind spots for one of the 1990s most “political” films.

Project Mayhem Richard Dyer writes: “entertainment provides alternatives to capitalism which will be met by capitalism” (qtd. in Britton 391). In other words, entertainment functions to meet deficiencies in people’s real lives. Accordingly, the utopian fantasies that the film constructs (the glamour of being a “bad girl”, the male-bonding through violence, the overthrowing of consumer society with Project Mayhem) are the alternatives (which are actually not alternatives at all) offered by capitalism. Indeed, in Tyler’s fantasy world, capitalism isn’t really the problem–the only thing stopping a young Indian convenience store worker from fulfilling his ambition of becoming a veterinarian (apart from the fact that Tyler might kill him) is the young worker himself.

The fatuousness of these fantasies is highlighted by Giroux’s observation that “class as a critical category is nonexistent in this film”. Indeed, when Tyler begins the process of re-channelling the energy of the Fight Club’s members into something more political, he sermonises that “a whole generation are pumping gas, waiting tables or [are] slaves in white collars”. No material distinction is made between an immigrant low-paid worker and an upper middle-class middle manager. Instead, class is effaced by Tyler’s quasi-evangelical philosophy: ”Our fathers were models for God […] We’re God’s unwanted children”. As the Fight Clubs are assimilated by Project Mayhem, Tyler is rendered a kind of urban David Koresh style father figure “whose public appeal is based on the attractions of the cult personality rather than on the strengths of an articulated, democratic notion of political [and economic] reform” (Giroux and Szeman qtd. in Lewis 99).

Tindall and Shi describe how “a burgeoning ‘militia’ or ‘patriot’ movement spread across the country in the 1990s” (1287). They recount that on April 19, 1995, which was “the second anniversary of the Waco incident [the razing of a compound in Texas during an FBI siege that cost the lives of at least 77 members of the Branch Davidions sect], a massive truck bomb exploded in front of the federal office buildings in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma” (1288). The three men convicted of the bombing were all militia members. This “brought to public attention the rise of right-wing militia groups” (Tindall and Shi 1288). While Tyler’s militia has nothing to do with patriotism (“Our war is a spiritual war. Our great depression is our lives”) and is, uniquely, an urban one, his paramilitary regimen and cod-philosophy are all too familiar.

Frederic Jameson has suggested late capitalism’s fragmented aesthetic (exemplified by Fight Club) “effectively abolishes any practical sense of the future and of the collective project, thereby abandoning the thinking of future change, to fantasies of sheer catastrophe and inexplicable cataclysm–from visions of terrorism on the social level to those of cancer on the personal”. At the start of the film Jack and Marla are fantasists feeding off other people’s (legitimate) misery at the cancer support groups they frequent and the sum off all this is found in Project Mayhem’s objective of destroying the world’s tallest building. Jack commits a final act of catastrophic self-abuse by pulling the trigger of a gun that he has placed inside his own mouth. By shooting himself Jack is freed from Tyler, but not the consequences of Tyler’s terrorist plotting. Jack and Marla look on helplessly as the adjacent buildings collapse to the strains of The Pixies’ “Where Is My Mind”. Of course, the “Ground Zero” references at the start and finish of Fight Club have, since the events of September 11th 2001, taken on new meaning.

Editor’s note – this article was subsequently developed into a longer piece: Bedford, M. (2011), ‘Smells like 1990s spirit: the dazzling deception of Fight Club‘s grunge aesthetic’, New Cinemas, 9: 1, pp.49-63, doi: 10.1386/ncin.9.1.49_1

References

Allen, Michael. Contemporary US Cinema. London: Pearson, 2003. Print.

Britton, Andrew. “Blissing Out: The Politics of Reaganite Entertainment”. Movie, 31/32 (1986): 1-42. Print.

Giroux, Henry. “Private Satisfactions and Public Disorders: Fight Club, Patriarchy, and the Politics of Masculine Violence”. Personal webpage. n.d. Web. 24.02. 2004.

Giroux, Henry and Szeman, Imre. “Ikea Boy Fights Back: Fight Club, Consumerism and the Political Limits of 1990s Cinema.” Lewis 95-105.

Jameson, Frederic. “Postmodernism, Or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism”. New Left Review. 146 (1984) 53-92. Print.

Lewis, Jon. Ed. The End of Cinema as We Know It. London: Pluto Press, 2001. Print.

Maltby, Richard. Hollywood Cinema. London: Blackwell, 1995. Print.

Palahniuk, Chuck. Fight Club. London: Vintage, 1996. Print.

Shi, David and Tindall, George. America: A Narrative History. New York: Norton, 2000. Print.

Taubin, Amy. “So Good it Hurts”. Sight and Sound. 9.11 (1999): 18. Print.

Whitehouse, Charles. “Review: Fight Club.” Sight and Sound. 9.12 (1999): n.p. Print.

Wood, Robin. Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan. New York: Columbia University Press, 1986. Print.

Wurtzel, Elizabeth. Prozac Nation. London: Quartet, 1995. Print.

—, Bitch. London: Quartet, 1998. Print.

Written by Mark Bedford (2004), London Metropolitan University; edited by Guy Westwell (2011), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2011 Mark Bedford/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post