Austin, Texas, 2005. Filmmakers Joe Swanberg, Andrew Bujalski and brothers Mark and Jay Duplass meet at the South by Southwest Film Festival (SXSW), unaware that their entries will soon be packaged and branded as the latest movement in American independent filmmaking. Kissing on the Mouth, Mutual Appreciation and The Puffy Chair all debuted at the festival and they, along with Bujalski’s first feature Funny Ha Ha (2002), formed the basis for mumblecore (usually spelt with a lower case ‘m’, a marker of its humble origins). Originally named as a joke by Bujalski’s sound mixer Eric Masunga, the term references the hallmark muffled dialogue of insecure characters and has become a significant phenomenon.

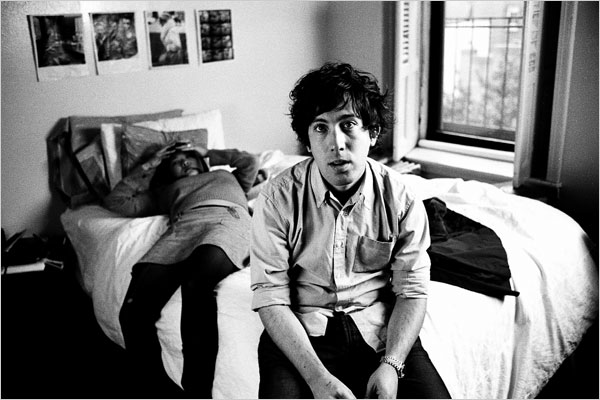

Following 2005, the directors remained in contact, working with each other on various projects. Mumblecore films are shot using digital video and share a lo-fi, realist aesthetic that gives shape to non-narratives about awkward, white middle-class twentysomethings inhabiting creative urban workspaces. The purpose of these American quasi-documentaries seems simple; to display everyday relationships and real events in the way they happen when there’s no Hollywood lighting, make-up, stars or soundtrack; and to indulge the voyeurism of the audience–the screen becomes a window through which they can watch unrehearsed vignettes of real-life. Indeed, Mumblecore’s “window-narratives” offer unenhanced stories based on the filmmakers’s own experiences, with intimacy issues and communication or lack thereof taking centre-stage. Due to their restricted budgets, typically less than $10,000 (Woodward), mumblecore filmmakers are inter-dependent, with actors, assistants, writers and musicians, including Aaron Katz, Greta Gerwig, Todd Rohal and Lynne Shelton, working across a range of projects in order to share labour costs and expertise. In terms of precursors, the mumblecore style has been likened to that of indie filmmaker John Cassavetes, whilst its idling, graduate characters are said to be modeled on those in Richard Linklater’s Slacker (1991).

Following 2005, the directors remained in contact, working with each other on various projects. Mumblecore films are shot using digital video and share a lo-fi, realist aesthetic that gives shape to non-narratives about awkward, white middle-class twentysomethings inhabiting creative urban workspaces. The purpose of these American quasi-documentaries seems simple; to display everyday relationships and real events in the way they happen when there’s no Hollywood lighting, make-up, stars or soundtrack; and to indulge the voyeurism of the audience–the screen becomes a window through which they can watch unrehearsed vignettes of real-life. Indeed, Mumblecore’s “window-narratives” offer unenhanced stories based on the filmmakers’s own experiences, with intimacy issues and communication or lack thereof taking centre-stage. Due to their restricted budgets, typically less than $10,000 (Woodward), mumblecore filmmakers are inter-dependent, with actors, assistants, writers and musicians, including Aaron Katz, Greta Gerwig, Todd Rohal and Lynne Shelton, working across a range of projects in order to share labour costs and expertise. In terms of precursors, the mumblecore style has been likened to that of indie filmmaker John Cassavetes, whilst its idling, graduate characters are said to be modeled on those in Richard Linklater’s Slacker (1991).

So, why did these films emerge? One answer to this question revolves around the filmmakers themselves. Having grown up in an age of home video and reality TV, the act of documenting the everyday seemed like a natural progression. Perhaps most importantly, these filmmakers of the so-called “Generation DIY” (Lim) began creating films at a time that coincided with the digital turn: digital video and home editing software was becoming increasingly accessible (allowing good quality films to be made on shoestring budgets) and advancements in the internet (high broadband speeds, low-cost providers, growing audiences for on-line content) placed filmmaking in the wider context of Myspace profiles, iPod playlists, and Youtube uploads. Mumblecore filmmakers inhabited, commented on, and exploited a world where the inter-compatibility of Netflix, Facebook, the iPad and iPhone, replaced the cinephile awaiting the newest cinematic release with the online spectator who streams new releases and expresses their opinion through blogging. Responding to the “immediacy and audacity”(Dentler) of this new on-line environment is a recurrent theme in mumblecore films, which might be read as explorations of the “struggl[e] for inter-personal communication during a telecommunications revolution” (Dentler). This is a key concern of Swanberg’s LOL (2006), for example, which shows how technologies such as instant messaging and email are often detrimental to clear communication.

Crucially, mumblecore filmmakers have shown that it is no longer necessary to find a distributor to invest large sums in advertising; instead free publicity can be gained through social networking sites, blogs and online articles. Use of this electronic ‘word of mouth’ is key to mumblecore’s success. Matt Dentler notes that “we live in a media era where everything is “My” this, “You” that, and “i” something, where a simple “send” or “publish” button could reach millions”. This offers independent filmmakers a new platform from which to launch their work. Furthermore, with the growing strength and popularity of online streaming sites such as Lovefilm, Netflix and iTunes, the films can be watched worldwide with merely a simple click. As Swanberg confirms, his films “typically do 20,000 orders on Video on Demand (VOD) [sites]” (Macaulay). In an interview with Filmmaker Magazine Rohal describes how people sent him messages through Myspace requesting to watch The Guatamalan Handshake (2006); he agreed only if they organized and promoted a local screening (Van Couvering).

Critics are divided on the merits of mumblecore. Whilst SXSW producer and Indiewire blogger Dentler celebrates the mumbled, philosophical commentaries on the social mores of modern communication, Film Comment critic Amy Taubin appears less convinced–at least in relation to mumblecore king, Swanberg, who has released at least one film a year since 2005. While Dentler applauds “[Swanberg’s] fearlessness at exploring intimacy”, Taubin refers to his talent for “getting attractive, seemingly intelligent women to drop their clothes and evince sexual interest in an array of slobby guys who suffer from severely arrested emotional development”. This is exemplified in Hannah Takes the Stairs (2007), as the main character (Gerwig) is oddly drawn to her less conventionally handsome, self-critical co-workers. Taubin does, however, commend films of fellow key mumblecore directors, Katz (whose films display a “lyric beauty rarely associated with digital cinematography”) and Bujalski (a “subtle writer […] who understands how to stage a scene so that body language speaks as strongly as words”). Other critics have heralded the films “painfully real”, “honest but not naive” and “canny but not fame hungry” (San Filippo). The term also divides the filmmakers it encompasses: Bujalski, has expressed worry at the reductive way in which the term is often used by critics to dismiss new mumblecore releases (Van Couvering). Conversely, Swanberg notes that by defining himself within the genre, he was able to increase publicity and awareness of his work. Exemplifying this, in August 2007, the Independent Film Channel Centre ran a mumblecore season entitled “The New Talkies- Generation DIY” (Lim).

Critics are divided on the merits of mumblecore. Whilst SXSW producer and Indiewire blogger Dentler celebrates the mumbled, philosophical commentaries on the social mores of modern communication, Film Comment critic Amy Taubin appears less convinced–at least in relation to mumblecore king, Swanberg, who has released at least one film a year since 2005. While Dentler applauds “[Swanberg’s] fearlessness at exploring intimacy”, Taubin refers to his talent for “getting attractive, seemingly intelligent women to drop their clothes and evince sexual interest in an array of slobby guys who suffer from severely arrested emotional development”. This is exemplified in Hannah Takes the Stairs (2007), as the main character (Gerwig) is oddly drawn to her less conventionally handsome, self-critical co-workers. Taubin does, however, commend films of fellow key mumblecore directors, Katz (whose films display a “lyric beauty rarely associated with digital cinematography”) and Bujalski (a “subtle writer […] who understands how to stage a scene so that body language speaks as strongly as words”). Other critics have heralded the films “painfully real”, “honest but not naive” and “canny but not fame hungry” (San Filippo). The term also divides the filmmakers it encompasses: Bujalski, has expressed worry at the reductive way in which the term is often used by critics to dismiss new mumblecore releases (Van Couvering). Conversely, Swanberg notes that by defining himself within the genre, he was able to increase publicity and awareness of his work. Exemplifying this, in August 2007, the Independent Film Channel Centre ran a mumblecore season entitled “The New Talkies- Generation DIY” (Lim).

At the time of writing [Spring, 2012], the ‘mumblecorps’ continue to maintain a strong festival presence; this year at SXSW the Duplass brothers will screen their new film The Do-Deca Pentathlon, alongside Swanberg’s collaborative project, V/H/S and Rohal’s Nature Calls. Whether these films will maintain their lo-fi, documentary approach and improvised ‘window-narratives’ or offer something entirely different is uncertain. Some critics have even proposed that we are in a post-mumblecore moment (San Filippo). As the directors have gained recognition, doors into the world of mainstream cinema have opened and, now approaching their thirties, the desire and need to make more money is growing. The latest Duplass film, Jeff Who Lives at Home (2011) stars Jason Segel and Hangover star, Ed Helms; a step away from the usual non-professional cast. Jeff is the second Duplass studio production after Cryus (2010) which saw John C. Reilly and Jonah Hill cast as leads. Assuming that the Duplass brother’s take on such projects in order to gain financial support, what is it that studios have to gain from investing in mumblecore? Essentially, Hollywood is buying into the mumblecore label; the indie-brand of unconfident, middle-class graduates and the awkward but meaningful silences that linger around them, incorporating “characters who are hard to like, but impossible not to sympathize with” (San Filippo). As if to map such a transition, core actor Greta Gerwig has recently appeared in Hollywood productions No Strings Attached (2011) and Arthur (2011) alongside stars Natalie Portman, Helen Mirren and Russell Brand. In these films her mumblecore past is more or less irrelevant as she is unknown to broader audiences. Her most prominent mainstream role however, has been in Greenberg (2010), in which she plays one half of an awkward duo with Ben Stiller. Whilst her other Hollywood appearances see her transformed, disconnected from her mumblecore roots, Greenberg recalls her former roles with a return to her signature matter-of-fact nakedness. In mumblecore films “there are no manicured Hollywood caresses, and the bodies portrayed are not Hollywood bodies”(Grose); Greenberg borrows this approach to nakedness and intimacy in a bid for authenticity and realism. Just as Gerwig’s roots in mumblecore are evident in Greenberg, the Duplass brothers’s use of well-known actors, and a studio style production process, allude to their earlier films in both Jeff Who Lives At Home and Cyrus. Both films feature socially dysfunctional characters who have experienced some sort of low-key failure–their reaction to which is to embark on a mumbled, almost directionless journey, continuing to move forward even though life is uncertain and they remain riddled with insecurities.

Though big name studios may borrow from the mumblecore brand, some members of the community remain focused on truly independent filmmaking. Bujalski’s upcoming film, Computer Chess (2012) has been crowd-funded through USA projects, who explain that “in such an expensive art form as film with its pre-determined commercial pressures, crowd sourcing […] is an integral way to support [Andrew]” (USA Projects). This illustrates how Bujalski can overcome financial hurdles without giving in to the pressures of the mainstream. Similarly, Swanberg has devised a new, entirely progressive way to finance films: through DVD and record label Factory 25, he is offering a one year subscription to his work. For $100, the mumblecore afficionado will receive a region free DVD boxset and unique additional material, including photos and soundtracks. Aware of the increasing use of torrents to download illegally, Swanberg claims that “everything gets pirated today anyway. It’s about all the other stuff, the records and books […] products I can have a tactile experience with”. He explains “if I can find 1,000 people to pay $100 a year for four of my movies, I can keep making movies” (Macaulay). That both Swanberg and Bujalski have confidence that their fans will support their work demonstrates their intention to continue making mumblecore.

At a time where technology is constantly changing and the internet and social media are now fully integrated into everyday life, digital arts such as film, photography and music have become more accessible. Although torrents, streaming and file sharing pose a threat to the income and thus funding of filmmakers and artists alike, the mumblecore filmmakers have found models for making and distributing distinctive films that inhabit and comment on this cultural moment. Mumblecore addresses these contemporary concerns in its thematic portrayal of people failing to communicate face-to-face, its DIY methods of production and its independence from conventional distribution and exhibition networks. The films successfully appeal to a generation of over-sharers who are permanently online, gently reminding them of the importance of the off-line inter-personal skills by which true connectivity takes place in the real world. The films of Swanberg and his friends might not be to everyone’s taste, but the self-sufficient way in which they are made and their encouragement to communicate and carry on regardless deserves commendation. If nothing else, the mumblecore movement demonstrate that independent filmmaking in the US is alive and well.

References

Dentler, Matt. “Indie Film for the Myspace/Youtube/iPod Generation.” Indiewire. Aug. 2007. Web. 4 Mar. 2012.

Grose, Jessica. “Naked Honesty”. The Slate Group. 1 Apr. 2010. Web. 4. Mar. 2012.

Lim, Dennis. “A Generation Finds its Mumble.” New York Times. 19 Aug. 2007. Web. 2 Mar. 2012

Macaulay, Scott. “Factory 25 Announce New DVD Subscription Series.” Filmmaker Magazine. 20 Sep. 2011. Web. 2 Mar. 2012

San Filippo, Maria. “A Cinema of Recession”. Cineaction!. 85. 2011. Web. 29 Feb. 2012.

Taubin, Amy. “Mumblecore: All Talk?”. Film Comment. n.d. Web. 27 Feb. 2012.

USA Projects. “Computer Chess by Andrew Bujalski”. USA Projects. n.d. Web. 2 Mar. 2012.

Van Couvering, Alicia. “What I Meant to Say”. Filmmaker Magazine. Spring 2007. Web. 2. Mar. 2012.

Woodward, Ricard B. “Mumblecore Realism in the Age of Technology”. The Wall Street Journal. 17 Mar. 2011. Web. 4 Mar. 2012.

Written by Amy Lewis (2012); edited by Guy Westwell (2012) Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2012 Amy Lewis/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post