Plot An economically deprived US city, 2008. In the run up to the 2008 presidential election, small time mobster Johnny Amato hires ex con Frankie to hold up an illegal mafia card game hosted by Markie Trattman. Since Markie has previously robbed his own game, the mafia will suspect him of orchestrating the heist again. Frankie persuades a reluctant Johnny to let him take fellow drug addled criminal Russell along to help him. Frankie and Russell rather haplessly pull the job off and a mafia fixer hires hit-man Jackie Cogan to execute the perpetrators of the robbery, and restore confidence amongst the local mafia. After Russell brags to a friend named Kenny, Cogan learns the truth about who organised and committed the robbery. Cogan persuades the fixer that Markie, Frankie and Johnny must be killed to get the game circuit back on track. He suggests bringing in fellow assassin “New York” Mickey to assist with the hits, only for the latter to prove a drunken liability. Russell is later arrested in a police sting attempting to sell heroin. Cogan tracks down Markie and shoots him in his car, then apprehends Frankie telling him he can win a reprieve if he assists with the hit on Johnny. Frankie nervously agrees and witnesses Cogan brutally shoot Johnny. Frankie is later killed when Cogan catches him unawares. On the night of Barack Obama’s election, Cogan meets the fixer in a bar to receive payment for his services. He is aggravated when he receives less than he expected (adapted from Johnston 79).

Film note A film with a small budget ($15m), an up-and-coming director and a major Hollywood star, Killing Them Softly is a surprisingly politically engaged piece of genre cinema. It demonstrates the extent to which stars can influence films not only by appearing in them but by controlling the production companies that make them, and comments acerbically on the economic meltdown that first hit the US in 2008, using its characters and scenarios to figuratively represent the causes and effects of the recession. To this end Killing Them Softly reconfigures some of the pre-established conventions of the gangster and crime film genres, and belongs firmly to a new cycle of films that comment on the economic crisis and the resulting anxieties felt by society.

Stars as producers Hollywood stars acting as film producers is not a new phenomenon, and dates back at least to 1919 and the formation of United Artists, a film studio founded by Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and D.W. Griffith (Cook 315-316). Unlike other major Hollywood studios, United Artists was not vertically integrated (it did not own production stages or cinema chains), and instead functioned as a distributor for films made by independent producers. As a result, it liberated its founders from the more restrictive and exploitative constraints of the major studios of the time (its model of negotiating distribution rights on an individual basis also anticipated the “package” led production method that developed after the decline of the studio system). During the 1930s United Artists were able to handle independent productions for the likes of David O. Selznick and Alexander Korda, as well as producing some of Charlie Chaplin’s most successful films, including Modern Times (1936).

While United Artists nearly failed after World War II, the general model of empowered producer-stars it offered has endured. For instance, during the demise of the US studio system in the late 1960s, rising film star Clint Eastwood set up his own production company using the money he made from starring in Sergio Leone’s Dollar Trilogy (1964, 1965, 1966). The Malpaso Company, as he named it, would go on to produce some of Eastwood’s most successful films of the 1960s and 70s, many directed by Don Siegel. Malpaso also helped facilitate Eastwood’s shift to being a writer-director as well as a star (Kapsis and Coblenz ix), allowing him to foster his own career by securing distribution for projects he had direct involvement in. He has directed 25 features to date, starring in almost all of them and winning two Academy Awards for direction.

Eastwood’s Malpaso may be a particularly noteworthy example, but in the post-studio era, film stars owning production companies (or acting as producers) has become commonplace, and appears to have increased since the 1990s. Concurrently, there has been a rise in film stars having personal managers rather than agents (Wasko 45-46). An acting agent predominantly seeks to secure their client roles; by contrast a personal manager provides career and business advice on a greater range of subjects (scripts, directors, release dates, etc.), carefully crafting a star’s persona based on the specific roles he or she plays. Some personal managers go so far as to act as producers on their clients’ feature films, leading some larger management companies to make “first look” deals with major studios, a fact that further reveals the shift of power dynamics toward the major star (McDonald 171-173).

Brad Pitt, for example, is represented by Brillstein-Grey Entertainment, an entertainment management company set up in 1986 by Bernie Brillstein and Brad Grey. Grey is one of the most successful entrepreneurs in the entertainment industry, becoming CEO of Paramount in 2006. Pitt founded Plan B Entertainment with Grey and his then partner, actress Jennifer Aniston, in 2002. To date, Plan B Entertainment has produced 19 feature films, five of which have starred Pitt, and the company has been instrumental in Andrew Dominik’s career as a Hollywood director. In 2000 Dominik’s independent debut Chopper won several awards and became a cult hit. Impressed with Chopper, and after having worked with the film’s lead Eric Bana, Pitt sought a meeting with Dominik. At this meeting Dominik pitched his script for The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (2007). Already impressed with Dominik’s work, Pitt agreed to produce the film and play Jesse James, and his involvement prompted Warner Bros to secure distribution rights. Major stars therefore have the power to get difficult films off the ground and into theatres, especially if they have their own production companies. As Dominik stated in an interview regarding Pitt’s involvement as both star and producer, “He’s powerful and he’s not afraid to use it” (qtd. in Levy).

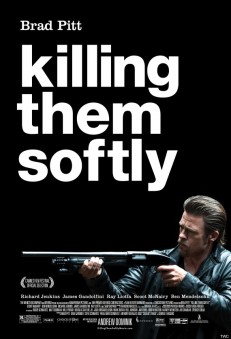

Pitt’s involvement in Dominik’s subsequent film Killing Them Softly had much the same effect, and he once again used his star power to draw in audiences and get the film made and distributed in the first place. Killing Them Softly contains an ensemble cast of established Hollywood actors, notably Ray Liotta, Richard Jenkins and James Gandolfini. Pitt’s character Jackie Cogan is not the only lead role in the film, and the narrative does not solely follow his movements. Nonetheless, the film’s marketing heavily uses Brad Pitt’s star image: the poster shows starkly in white on black Brad Pitt’s name (and no-one else’s) above the film’s title. Moreover, Pitt’s character Cogan is the only character to appear on the poster. Other modestly-budgeted films produced by Plan B Entertainment and starring Pitt (including The Tree of Life (2011) and 12 Years a Slave (2013)) have used his star persona in a similar manner. The involvement of his production company also allows Pitt to take roles that develop and enhance his persona. In Dominik’s films, Pitt portrays not heartthrobs but starkly uncompromising – and very human – individuals. (Surprisingly, though Pitt has received three Academy Award nominations, two of them since establishing Plan B, he has yet to be nominated for a performance-related Academy Award for one of the films he has produced).

There are of course other actor/producers in Hollywood who carry a similar level of influence to Pitt. Tom Cruise set up Cruise/Wagner Productions with casting agent and film executive Paula Wagner in 1993, and this allowed him to control his star persona throughout the 1990s and benefit from several highly profitable films (Clark). More recently, George Clooney set up Smokehouse Pictures in 2006 with writer/director Grant Heslov, signing a production and development agreement with Warner Bros pictures and television (Anon). Smokehouse has since produced eight features, with Clooney directing three of them and starring in four. As these examples show, a trend that started in the studio era with United Artists continues to see actors become involved in almost all aspects of film production, permitting challenging films such as Killing Them Softly to be made and distributed internationally.

Allegory of a recession Killing Them Softly is adapted from the 1974 novel Cogan’s Trade by George V. Higgins, although the book’s story of economic crisis within an illegal gambling circuit was updated to 2008 because Dominik felt the themes of the book were entirely suited to the global economic crisis that started at this time (Solis). This crisis, developing into an economic recession currently still affecting the US and elsewhere, is central to understanding the film. While the causes are complex, the crisis principally arose due to the bursting of the US subprime mortgage market bubble in 2007: since 49 per cent of the US banking system was made up of mortgage-based assets, this had a profound effect on the economy. Exacerbating this was a global credit crisis resulting from myriad (often criminal) manipulations of a range of financial processes and products. Economists believe the resulting financial crisis to be the worst since the Great Depression of the 1930s (Chorafas 89-95). 2008 also represents a significant year in American politics: Barack Obama was at this time elected on a platform of hope and change, promises that – in the wake of continuing economic turmoil – have proved difficult to uphold.

The opening sequence of the film uses a rather avant-garde style of editing, cutting abruptly between black on white opening credits and a slow motion shot of Scoot McNairy’s dishevelled and hunched character Frankie walking into a blustery and destitute looking street. During this, a campaign speech from Obama can be heard repeating the word “America”, his voice harshly coming and going with each cut. Frankie is finally framed beneath two adjoining campaign billboards, one showing John McCain with two thumbs raised and the slogan “Keeping America Strong”, the other the smiling face of Obama and the slogan “Time for Change”. This sequence not only locates the audience within the chosen period, but highlights the sudden plunge into economic hardship which the US is facing. The joint billboard slogans cast a critical retrospective light on current state of the US, as many years on from 2008 the country is still feeling the effects of the economic downturn.

Other key scenes in the film, such as Frankie and Russell’s heist, or the first meeting between Cogan and “The Fixer” (a middle-man for the mob, played by Richard Jenkins), play out alongside radio soundbites commenting on the economic crisis from George W. Bush, Obama, McCain and Henry Paulson (then Secretary of the Treasury). These highlight how the film’s narrative of an illegal economy being brought to its knees through previous failures to regulate, failures which lead high-ups to try to restore confidence in the system, reflect events of 2008. The scheme cooked up by Johnny Amato (Vincent Curatola), Frankie and Russell (Ben Mendelsohn) to benefit from this lack of regulation becomes, then, something of an allegory for the events that led to the banking crisis. Johnny appears not to have full faith in Frankie and Russell’s ability to rob the card game, but feels the reward outweighs the risk, making this criminal trio akin to certain cavalier sectors of the banking sector. Such bankers convinced socioeconomically deprived clients to accept so called “liar loans” that they had no real hope of repaying, so that the bankers could then chase fees connected with selling such loans (Chorafas 90). The soundtrack offers a suspiciously ironic commentary on these economic themes, songs like “Life is Just a Bowl of Cherries” and “Money (That’s What I Want)” being purposefully played during scenes of drab economically deprived streets, themselves reminiscent of scenes from the Great Depression.

One of the most compelling aspects of the film’s allegory is the killing of Markie Trattman (Ray Liotta). Although Trattman is innocent, his previous misdemeanours prompt Cogan to argue that his murder is necessary for the restoration of trust in the gambling circuit. As The Fixer puts it, the killing is important for “the public angle.” Innocence and guilt become secondary to consumer confidence, much in the same way as public perception of restored confidence in the banking system is deemed more important than the reality of the amount of toxic debt incurred (Johnston 79). Other characters and situations encourage an allegorical reading of the film. The sheer bureaucratic indecisiveness and relentless cost-benefit evaluation that The Fixer performs is indicative of the measures put in place by the US government to try and regulate the banks after the economic crisis. The character of “New York” Mickey (James Gandolfini), brought in at Cogan’s behest, is initially heralded as a respected professional contract killer. However, Mickey proves to be a liability and is unable to complete his contract due to his alcoholism and womanising. The largest bankruptcy in US history occurred in September 2008 when Lehman Brothers Holdings filed for bankruptcy, owing more than $600m in debt (Mamudi). Prior to this, Lehman Brothers was the fourth largest investment bank in the US, and was a highly respected institution. Like the Lehman Brothers, Mickey was once deemed dependable by his associates, but through self-debasement has fallen from grace and is rendered useless.

Gangsters in crisis These allegorical elements sit comfortably alongside the film’s gangster genre trappings. Since its heyday in the 1930s, this genre has gone through many permutations, but generally speaking comes with certain expectations. Visual iconography will likely include urban ghetto settings, stylish costumes and adornments, character machismo and the use of firearms (Mitchell 219). The contemporary gangster film has also benefitted from increasingly relaxed censorship laws, depicting as a result more visceral and realistic accounts of organised crime and violent acts.

Killing Them Softly takes place in a contemporary setting and transforms many of these established visual motifs in order to enhance its critical commentary on the economic crisis. None of the gangsters wear the smart attire audiences have become accustomed to. The film instead chooses to depict so-called “mid-level” characters as opposed to Mob bosses, the latter occasionally referred to but never seen. The settings of derelict, litter-strewn ghettos and boarded up houses (the result of the mass repossessions caused by the economic crisis) also deglamorise this kind of lifestyle. Instead of the fashionable nightclubs or restaurants so often depicted, the characters in Killing Them Softly inhabit grimy backroom poker games and seedy dive bars. Moreover, the violence of the film is either shockingly unpleasant (as when Trattman is beaten) or ironically elegant (as in his later murder, depicted in graceful slow motion).

Perhaps most interesting is the film’s treatment of the macho gangster character. Many of the actors are associated with confident, assertive masculinity, fostered by playing formidable roles in previous crime films and television shows. James Gandolfini and Vincent Curatola both established themselves in the HBO series The Sopranos (1999-2007), a popular show that depicted the lives of present day New Jersey mafia. Ray Liotta established himself playing the gangster Henry Hill in Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990). In Killing Them Softly however, their characters are hapless, downtrodden and somehow vulnerable. Hoping to get by on charm or quick fixes, they all meet their demise when they fail to adapt to a changing environment. In this way, Killing Them Softly paints a sceptical picture of organised crime, rather than the glamorous one to which we have become accustomed. The exciting illegality, illicit wealth and freedom from social constraint that often differentiate gangsters from ordinary citizens has here been replaced by small-time scheming, incompetence and fallibility.

In his own discussion of modern gangster films, Steve Neale (34-39) categorises them according to either their “Mafia mystique” or their inclusion of wiseguys, hit-men and heists. The former is personified by The Godfather (1972), and remains popular, as evinced by the likes of Road To Perdition (2002), Public Enemies (2009) and Lawless (2012); the pinnacle of the latter is probably Goodfellas, while other notable examples include Carlito’s Way (1993) and Pulp Fiction (1994). Whilst Killing Them Softly is undeniably a gangster film, and contains elements that link it to this second category (Frankie and Russell pull off a heist and Cogan is a hit-man), the criminal element feels somehow secondary to the economic critique the film sets out to make. The gangsters appear as people who are simply going about their day job, with the same obstacles and anxieties faced by ordinary people.

In its final moments, the film reveals how pessimistic it is about not only the current state of the US, but also the country’s entire history. Meeting the Fixer in order to get paid, Cogan is shocked to find himself being short-changed. When the Fixer tries to change the subject to a television broadcast of Obama’s “One Nation” speech and its reference to Thomas Jefferson, Cogan blasts Jefferson for being a slave-owning capitalist and a “rich white snob.” Cogan entirely rejects the idea of the US being a community, stating by contrast that “in America you’re on your own. America’s not a country. It’s just a business. Now fucking pay me.” Here, as in Trattman’s unwarranted death and Mickey’s alcoholism, the film rejects not only the clichés of the gangster genre but also of US nationalism. Cogan is not an unusual character for being concerned only with the bottom line, but he is unusual in being so open about it (something that itself contrasts with Pitt’s normally heroic onscreen persona).

Killing Them Softly is as much a film about capitalism as about gangsters. Of course, organised crime could be said to represent capitalism in its most brutal form, since its sole purpose is to make money through whatever means necessary. Such an equation is not novel (Johnston 78). However, as capitalism is currently going through a crisis, Killing Them Softly seeks to represent this crisis within its narrative of organised crime. Rather than a simple gangster film, Killing Them Softly can productively be placed amongst films which deal with the recession, or with corporate greed. Since the economic crisis films such as Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (2010), Margin Call (2011) and The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) have dealt directly with the greed and corporate corruption that lead to the crisis. On the other hand, films like Out of the Furnace (2013) chart the desperate lives of ordinary people living in a recession. Killing Them Softly allegorically shows both perspectives (the masters of the universe and the people being mastered), expressing in the process contemporary social anxieties about the economy using the gangster milieu.

References

Anon. “George Clooney’s Smokehouse Signs First Look Deal with WB.” M&C News. 21 Jul. 2006. Web. 05 Jan. 2014.

Chorafas, Dimitris N. Financial Boom and Gloom: The Credit and Banking Crisis of 2007-2009 and Beyond. Chippenham: Palgrave Macmillian, 2009. Print.

Clark, John. “The Business of Cruise Control.” New York Daily News. 23 Aug. 2007. Web. 31 Jul. 2014.

Cook, David A. A History of Narrative Film. New York & London: W.W. Norton & Company, 1990. Print.

Johnston, Trevor. “Review: Killing Them Softly.” Sight and Sound 22.10 (2012): 78–79. Print.

Kapsis, Robert E and Kathie Coblentz. “Introduction.” Clint Eastwood: Interviews. Ed. Robert E. Kapsis and Kathie Coblentz. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1999. vii–xx. Print.

Levy, Emanuel. “Assassination of Jesse James: Andrew Dominik.” Emanuel Levy. 09 Nov. 2007. Web. 25 Mar 2014.

Mamudi, Sam. “Lehman Folds with Record $613billion Debt.” Market Watch. 15 Sep. 2008. Web. 04 Jan. 2014.

McDonald, Paul. “The Star System: The Production of Hollywood Stardom in the Post-Studio Era.” The Contemporary Hollywood Film Industry. Eds. Paul McDonald and Janet Wasko. Oxford: Blackwell, 2008. 167–181. Print.

Mitchell, Edward. “Apes and Essences: Some Sources of Significance on the American Gangster Film.” Film Genre Reader III. Ed. Barry Keith Grant. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010. 219–228.

Neale, Steve. “Westerns and Gangster Films Since the 1970s.” Genre and Contemporary Hollywood. Ed. Steve Neale. London: British Film Institute, 2002. 34–40. Print.

Solis, Jose. “Killing Them Softly: An Interview with Andrew Dominik.” PopMatters. 05 Dec. 2012. Web. 16 Nov. 2013.

Wasko, Janet. “Financing and Production: Creating the Hollywood Film Commodity.” The Contemporary Hollywood Film Industry. Eds. Paul McDonald and Janet Wasko. Oxford: Blackwell, 2008. 43–62. Print.

Written by Benjamin Skyrme (2013); edited by Nick Jones (2014), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Selling without prior written consent prohibited. Please obtain permission before redistributing. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2014 Benjamin Skyrme/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post