Plot Eight years after the death of district attorney Harvey Dent, Bruce Wayne has become a recluse, broken by the death of his childhood sweetheart Rachel Dawes and has retired as the vigilante Batman after taking the blame for Dent’s crimes, as well as Dent’s death. Cat burglar Selina Kyle kidnaps congressman Byron Gilley and arranges a deal with Phillip Stryver. Stryver double-crosses Kyle, but she uses Gilley’s phone to alert the police. Commissioner Gordon and the police arrive to find the congressman, and then pursue Stryver’s men into the sewers while Selina flees. The police are killed and Gordon is captured. He is taken to Bane, a masked mercenary but escapes. Bane and multiple accomplices attack the Gotham Stock Exchange. Kyle agrees to take Batman to Bane but instead leads him into Bane’s trap. Bane reveals that he intends to fulfill Ra’s al Ghul’s mission to destroy Gotham and imprisons Wayne. Bane lures Gotham police underground and traps them there. Bane uses a nuclear bomb to hold the city hostage and isolate Gotham from the world. Bane releases the prisoners of Blackgate Penitentiary, initiating anarchy. Wayne escapes from the prison and enlists Kyle, Blake, Tate, Gordon, and Lucius Fox to help stop the bomb’s detonation. While the police and Bane’s forces clash, Batman overpowers Bane. He interrogates Bane for the bomb’s trigger, but Tate intervenes and stabs him. She reveals herself to be Talia al Ghul, Ra’s al Ghul’s daughter. She uses the detonator, but Gordon blocks her signal, preventing remote detonation. Talia leaves to find the bomb while Bane prepares to kill Batman, but Kyle returns on the Batpod and saves Batman by killing Bane. Batman and Kyle pursue Talia, hoping to bring the bomb back to the reactor chamber where it can be stabilized. Talia’s truck crashes, but she remotely floods and destroys the reactor chamber before dying. With no way to stop the detonation, Batman uses the Batpod to haul the bomb over the bay, where it detonates.

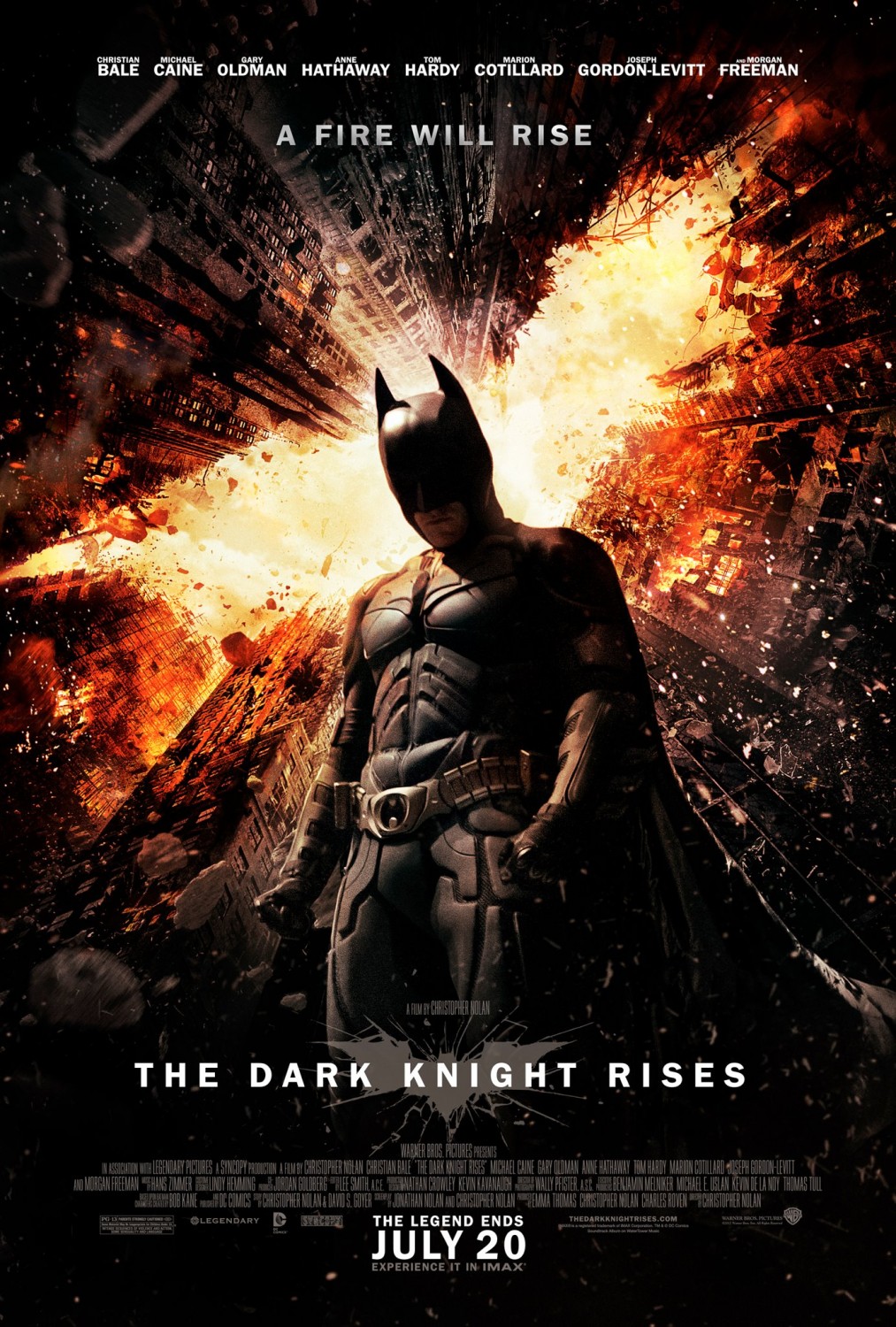

Film note The Dark Knight Rises is the conclusion to Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy and opened in major territories on July 20th 2012. As of December 2013, it remains the most commercially successful 2D film in the US, taking $160.9m at the box office in its opening weekend. Despite the stratospheric expectations of this third installment, it is arugable that The Dark Knight Rises underperformed, since the Colorado shootings “deterred some of the potential audience” (Acuna). In fact, the film will forever be associated with the midnight shooting in the town of Aurora, which left twelve people dead. It is a case of “tragic life-imitating-art” (Zeitchik), with the shooter dressing in attire inspired by the Joker from the previous sequel, and carrying out the shootings during the gunshot-heavy opening scene. However, despite this setback the $250m film maintained a strong box-office taking of $1.084 billion, ending the year as the 3rd highest-grossing film ever worldwide. The film has also attracted considerable criticism, with the entire trilogy scrutinized as being “more explicitly right-wing than almost any Hollywood blockbuster of recent memory” (Douthat) and Nolan’s Bruce Wayne/Batman claimed to be a post-9/11 vigilante, who in a time of war on terror, political unease and economic downturn, registers the violent, almost fascistic fantasies of a frightened population.

The Batman franchise Centering on a character created by Bob Kane and Bill Finger the Batman franchise originated with a comic book in 1939, long before Nolan completed his “bruising saga of revolution and redemption” (2012). Will Brooker argues that Batman’s “position as a cultural icon is […] due to the extent to which he can adapt within key parameters” (40), implying that a sense of familiarity must remain in his characterisation to keep the older generation satisfied, while also adapting to keep a younger audience interested and so ensure that the franchise stays relevant. Even though Batman comics have been in publication for more than seventy years, his first iconic on-screen appearance was an ABC television show. Bill Boichel notes that “by 1965 the pop/camp movement, at the height of fashion, had repositioned and revalued comic books as central to its aesthetic” (14). This is evidently the reason behind the way in which the television series and the film Batman (1966) portrayed the superhero with a histrionic display of showy costumes and gadgets all named Bat-something. It was successful because the years it aired were a time of vibrancy and Pop Art in the style of Andy Warhol.

When Warner Communications acquired DC Comics in 1971, their intention was to secure licensing revenues and materials for film adaptations. Meehan claims that by issuing The Dark Knight Returns (1986) by Frank Miller in comic form, they were test marketing a darker reinterpretation of Batman with an adult readership “whose experience with the character would include the camp crusader of the 1960s” (Meehan in Pearson 53). The success of the comic convinced Warner that audiences were ready for this darker Batman, since two years later Tim Burton was brought in to make Batman (1989) for the 50th anniversary of the character. The decision of Warner to finance the film as well as distribute it meant Batman achieved the status of an in-house blockbuster. Boichel states that 1989 “became the year of the bat” (17), with Batman grossing over $411m worldwide, on a budget of around $35m. Burton’s Batman was followed by Batman Forever (1995) and Batman & Robin (1997). These films, especially the latter, returned to a tone “not a word away from the TV show” (Brooker 294). Alex Ross reviewed Batman & Robin, saying that “it looks bad: cluttered surfaces, production design reminiscent of overblown Broadway musicals” (1997). The critical and commercial failure of these latter two films kept the Batman film franchise dormant for years, until the “more cynical, but more fearful post-9/11” (Booker 31) reboot by Nolan.

Contracted by Warner to relaunch the Batman franchise, Nolan was given creative freedom by the studio. Nolan’s team made “a conscious attempt to eliminate the camp and the cartoonish elements” (O’Neil 170) and return to a darker tone. Following Frank Miller, who commented “I simply put Batman, this unearthly force, into a world that’s closer to the one I know” (Sharrett in Pearson 39), Nolan created a Gotham City “decidedly more realistic” (Booker 27). Tonally, Nolan’s trilogy is similar to the films of Burton, as well as the graphic novels of the 1980s created by Miller and Alan Moore, (Moore wrote Batman: The Killing Joke, 1988). The Dark Knight Rises is deeply inspired by The Dark Knight Returns, as well as by Batman: Knightfall (1993) by Moench and Batman: No Man’s Land (1999) by Gorfinkel, all of which employ an approach analogous to that of Miller in the previous decade and portray Batman as “a radical opponent to the status quo” (Sharrett in Pearson 33). Following this dark trajectory, Batman Begins (2005) is symptomatic of a culture of fear post-9/11, while The Dark Knight (2008) is interpreted as a response to terrorism with the Joker constantly demonstrating his love for “dynamite, and gunpowder, and gasoline!”. Following this The Dark Knight Rises maintains “considerable attention to potential acts of terrorism” (Markert 280) as well as political resistance, as they shape US society. Roger Ebert notes that The Dark Knight Rises “leaves the fanciful early days of the superhero genre far behind, and moves into a doom-shrouded, apocalyptic future that seems uncomfortably close to today’s headlines” (2012).

The ‘99%’ The Dark Knight Rises has been read as a political commentary, since Nolan “pushes the Batman legend to its logical extreme” (O’Hehir). Some claim the film to be radically conservative, with the multi-billionaire Bruce Wayne (Christian Bale) as savior, advancing a “serious, stirring proposal that the wish-fulfilment of the wealthy is to be championed if they say they want to do good” (Shoard). Andrew O’Hehir even claims that “the ‘Dark Knight’ universe is fascistic”.

Certainly, The Dark Knight Rises has anti-communist undertones, since the antagonist Bane (Tom Hardy) is a radical mercenary calling himself ‘Gotham’s reckoning’, giving speeches about returning Gotham back to the ‘people’, while there are fast edits showing wealthy people being pulled out of their penthouses and beaten. This editing pattern provokes sympathy for the wealthy capitalists. Conversely, the anarchic intentions of Bane are shown to be funded by John Daggett, a shareholder of capitalist Wayne Enterprises and the fact that the bomb is initially a fusion reactor created just by Wayne Enterprises establishes that “the good work done by corporations can be turned into a negative force” (Marcotte).

Conservative radio host Limbaugh claimed, regarding the last presidential election, that Wayne resembles losing candidate Mitt Romney, while also claiming that the main antagonist, Bane, is a reference to the former company of Romney, Bain Capital. Of course, this is unlikely since Bane has been a Batman villain since his first appearance in the comics in 1993, but it does indicate how the film activated strong political readings, with Nolan provocatively demonstrating a “tale of underclass resentment, of an uprising by the lower half of the 99% that is turned to evil purposes” (O’Hehir). With characters such as Bane exemplifying class warfare, the film is relatable to “the Occupy Wall Street protests, the aftermath of the 2008 economic meltdown, and the subsequent polarization of American politics” (Miles). It is claimed Nolan read Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities (1859) before making the film, which may account for the starkness of Gotham falling under a tyrannical, revolutionary regime “closely modelled on the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror” (O’Hehir).

The raid perpetrated by Bane on the ‘Wall Street’ of Gotham demonstrates the extreme capitalist ideal that “money is power, and those without money hold very little power” (Donarum). Like the second chapter of the trilogy, the last was released on the eve of the American Presidential election, with the economy one of the main issues being debated. Bane claims that he is fighting a class war against the privileged people of Gotham for the 99%, but the dramatic irony is in the fact that we learn quite early what his real intentions are: to destroy Gotham, fulfilling the mission of Ra’s Al Ghul. His malicious anarchy is at its most potent in the football field scene, beginning with a young boy singing the national anthem. As Bane waits in the tunnel he announces: “Let the games begin”, leading to mass destruction and the trapping of the majority of the police of Gotham in the sewers. His leftist rhetoric alongside his unleashing of destruction on the wealthy “can be read as a slam against the left” (Marcotte), but maybe this is not Nolan completely sympathising with the right. Bane is a vision of anarchy gone to evil extremes, so perhaps Nolan wishes to warn that even progressive messages “can mutate quickly” (Zeitchik).

The film folds communism and capitalism together, with critique spread fairly evenly across the two ideological systems. Perhaps intentionally, it is difficult for the viewer to ascertain fully which group to root. However, the film allegiances can be glimpsed by looking at the character of Selina Kyle/Catwoman (Anne Hathaway). She is shown to represent the 99% and directly asks Wayne: “how you ever thought you could live so large and leave so little for the rest of us” and her story exemplifies how “a corrupt justice system ends up creating more violent crime” (Marcotte). However, in the end, after seeing what Bane’s radical vision of “equality” has done to Gotham, she helps the very member of the 1% she ridiculed. As such, Catherine Shoard is persuasive when she argues that the film “indulges in much guttural talk of the gap between the 99% and the 1%, but it is the former who are demonised”. Mark Fisher comments that The Dark Knight Rises “isn’t the simple conservative parable that rightwingers would like, but it is in the end a reactionary vision”. Indeed, when dealing with Batman as the main protagonist, one must be prepared to accept that his films are advocating capitalism, since Bruce Wayne is a man of extreme wealth, who the audience is asked to identify with as he strives to end corruption in Gotham for an entire trilogy.

Militarised philanthropy The recent cycle of superhero films have been criticised for being “insanely expensive ‘tentpole’ films” (Queenan), churning out the same narratives in order to make a quick profit. Yet, their success also stems from their ability to capture a “current mood of uncertainty and dread”, especially via the redemptive role of their central characters (Queenan). Faludi argues that after 9/11, “a narrative was created and populated with pasteboard protagonists whose exploits would exist almost entirely in the realm of American archetype and American fantasy” (64). As such Wayne/Batman represents the moralistic hero that post-9/11 America wants to protect them. In this he has much in common with fellow billionaire philanthropist, Tony Stark/Iron Man (Robert Downey Jr.) While Wayne intends to develop a clean energy project with a fusion reactor, in The Avengers (2012) Stark turns his military weapons empire into an energy project. In Iron Man 3 (2013), Mandarin (Ben Kingsley) is portrayed as a Bin Laden-type terrorist leader, while in the opening of The Dark Knight Rises Bane kills CIA agents on an airplane. Moreover, in this latter film, the attack has philanthropist Tate/Talia (Marion Cotillard) as the real instigator, while in the former Killian (Guy Pearce), another corporate executive, is revealed as the actual terrorist. In the case of Wayne and Stark, both characters demonstrate this sense of American heroism, with the former protecting Gotham, the fictional New York, while Stark saves the President from Killian. They have differing approaches to the fight on crime, with Wayne hiding his identity, while Stark openly admits he is Iron Man, but both billionaires truly establish themselves as superheroes in their respective final films. In fact, the two men are placed in scenarios whereby they are stripped of their wealth, and can only rely on their strength and ingenuity. While Wayne literally rises from the pit to save Gotham, Stark uses his intelligence to make weapons and protect his city.

Ultimately, The Dark Knight Rises is not asserting that Occupy Wall Street is overtly wrong, nor advocating capitalism wholeheartedly, but “compound[ing] them to a ‘worst case scenario’ place” (Donarum). Nolan’s film criticizes capitalism especially for the moral corruption that has affected its main exponents, who now live out of touch, almost completely separated from the most part of society that they dislike and fear. Therefore, the film and the whole trilogy indicates how various evil forces can obtain great advantage and opportunities from such a polarized and unequal situation. The solution proposed is to restore social care and moral values under the governance of a powerful patrician elite. In essence, this is the aim of Bruce Wayne and Tony Stark, and the wider cycle: to advocate on behalf of a resourceful, moral and monied ruling elite.

References

Acuna, Kirsten. “IT’S OFFICIAL: ‘The Dark Knight Rises’ Nabs The Highest-Grossing 2D Opening Weekend Ever.” Business Insider. Business Insider Inc. 24 Jul. 2012. Web. 1 Dec. 2013.

Boichel, Bill. “Batman: Commodity as Myth.” The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and his Media. Eds. Roberta E. Pearson, and William Uricchio. London: BFI Publishing, (1991): 4-17. Print.

Booker, M. Keith. “May Contain Graphic Material”: Comic Books, Graphic Novels, and Film. Westport: Greenwood Publishing, (2007). Print.

Brooker, Will. Batman Unmasked: Analyzing a Cultural Icon. New York: Continuum Publishing, (2001). Print.

Donarum, Nathan. “The Dark Knight Trilogy and 9/11”. The Racked Focus. n. p. 18 Aug. 2012. Web. 10 Dec. 2013.

Douthat, Ross. “The Politics of ‘The Dark Knight Rises’.” The New York Times. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. 23 Jul. 2012. Web. 25 Oct. 2013.

Ebert, Roger. “Review: The Dark Knight Rises.” Chicago Sun-Times. Tim Knight. 17 Jul. 2012. Web. 25 Oct. 2013.

Faludi, Susan. The Terror Dream: What 9/11 Revealed about America. London: Atlantic Books, (2007). Print.

Fisher, Mark. “Batman’s political right turn.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies. 22 Jul. 2012. Web. 20 Dec 2013.

Marcotte, Amanda. “The Masked Morality of the Batman Trilogy.” The American Prospect. The American Prospect, Inc. 27 Jul. 2012. Web. 10 Oct. 2013.

Markert, John. Post-9/11 Cinema: Through a Lens Darkly. Plymouth: Scarecrow Press, (2011). Print.

Miles, Derek. “Dark Knight Rises Movie: Why Occupy Wall Street will be featured in the Batman film.” Art. Mic. Mic Network Inc. 12 Jul. 2012. Web. 10 Dec. 2013.

O’Hehir, Andrew. “‘The Dark Knight Rises’: Christopher Nolan’s evil masterpiece.” Salon, Salon Media Group. 18 Jul. 2012. Web. 5 Dec. 2013.

O’Neil, Dennis. Batman Unauthorised: Vigilantes, Jokers, and Heroes in Gotham City. Dallas: Ben Bella Books, (2008). Print.

Pearson, Roberta E., and Uricchio, William. The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and his Media. London: BFI Publishing, (1991). Print.

Queenan, Joe. “Man of Steel: does Hollywood need saving from superheroes?” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies. 11 Jun. 2013. Web. 5 Jan. 2014.

Ross, Alex. “The Schumacher Hypothesis.” Slate, The Slate Group. 22 Jun. 1997. Web. 20 Dec. 2013.

Shapiro, Ben. “LA Times can’t believe ‘Dark Knight Rises’ portrays communism negatively.” Breitbart.com. n. p. 23 Jul. 2012. Web. 20 Nov. 2013.

Shoard, Catherine. “Dark Knight Rises: fancy a capitalist caped crusader as your superhero?” The Guardian. 17 Jul. 2012. Web. 25 Oct. 2013.

Shone, Tom. “The Dark Knight trilogy as our generation’s Godfather.” The Guardian. 20 Jun. 2012. Web. 30 Oct. 2013.

Zeitchik, Steven. “Aurora: ‘Dark Knight Rises’ shootings have eerie overtones.” Los Angeles Times. 20 Jul. 2012. Web. 1 Dec. 2013.

Written by Itteshad Hossain (2014); edited by Alex De Gironimo (2015), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2014 Itteshad Hossain/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post