Plot Having been uprooted from her life in Minnesota, eleven-year-old Riley struggles to adjust to her new life in San Francisco. Her emotions – Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear, and Disgust – guide her via a control centre in her mind where Joy especially works tirelessly to record new memories in special orbs. Riley’s most important core memories are housed in the Headquarters, powering five islands of her personality. After Sadness accidentally creates a sad core memory, causing Riley to cry in front of her new class, Joy attempts to destroy the orb. This displaces the other core memories, shutting down the personality islands and ejecting Joy and Sadness into the expanse of Riley’s long-term memory. Attempting to return to Headquarters, the two seek help from Riley’s childhood imaginary friend, Bing Bong. Meanwhile, Anger, Fear, and Disgust unintentionally distance Riley from her loved ones. As a result, her personality islands are destroyed and Joy and Bing Bong are flung into Riley’s Memory Dump. Frantically searching through forgotten memories, Joy discovers a sad memory that becomes happy, causing an epiphany that reveals Sadness’ vital importance in Riley’s life. Aided by Bing Bong’s sacrifice, Joy is able to return to Headquarters with Sadness to stop Riley from running away. Giving Sadness the controls, Joy and the other emotions watch as Sadness convinces her to return to her family, creating a new type of core memory that is dually happy and sad. Riley adjusts to her life in San Francisco and her emotions work together to regulate her life as she continues to grow into a young adult.

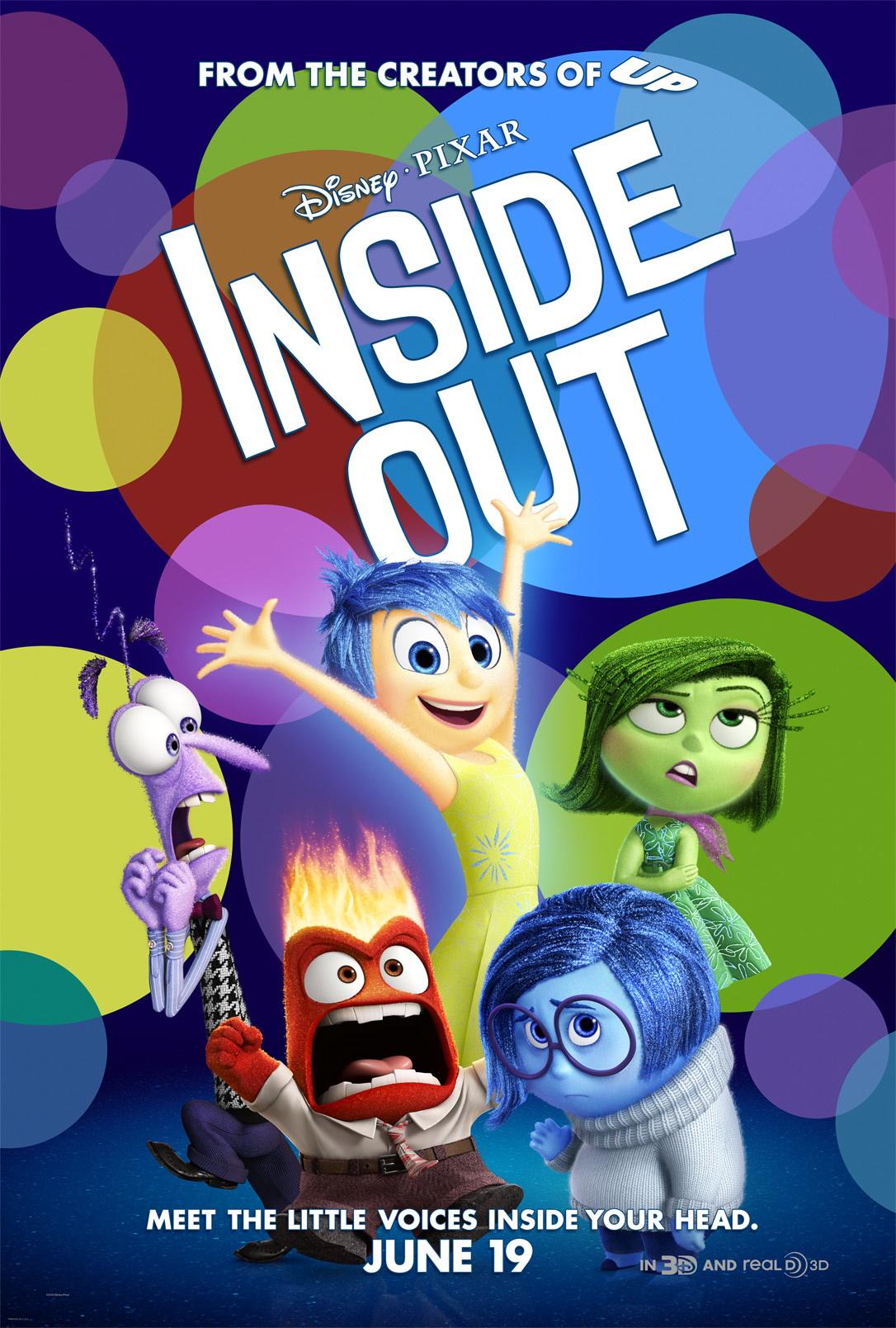

Film note Inspired by director Pete Docter’s own daughter, Inside Out is a 2015 co-production between Pixar Animation Studios and Walt Disney Pictures, both of which are owned and operated by the mass media conglomerate, The Walt Disney Company. Originally competitors, Pixar was purchased by Disney in 2006 and though the two remain separate entities, they consistently produce successful films together. With the “biggest original box office debut in history”, Inside Out is no exception (Terrero). The film grossed nearly $854m worldwide, and more than quadrupled its expensive $175m budget. Much of the film’s success can be attributed to its wide appeal and innovation in tapping into the prominent issue of depression through a unique and touching perspective.

“I would die for Riley” Until 2012 with the release of Brave, all of Pixar’s “unfathomably successful movies […] [had] male leads” usually in the form of non-human characters (Stein). This contrasted with the stereotypical Disney film, whose protagonists are always princesses, and set Pixar apart from their parent company. Compared to the “Disney formula […] of princesses and fairy-tale fantasies, Pixar’s stories are perceived as fresh and innovative”, however their refusal to include average female characters with average female problems is anything but (Ebrahim 44).

The third original Disney-Pixar film, Brave certainly signified a departure from the Pixar norm as it finally ventured into the world of female protagonists, and female directors – albeit briefly. Yet by attempting to reinvent the classic Disney princess story and avoid the “gender stereotypes” Disney is known to perpetrate in its films, Pixar removed the emphasis on romance in favour of permitting Merida “to be another female stereotype, the tomboy” (Dockterman). By de-feminising the princess and placing more emphasis on archery and action, academic Lissa Paul notes that Pixar created a “female [character] who [takes] on traditionally male characteristics in an attempt to subvert the kinds of traditional female roles […] Disney princesses have taken on” (qtd. in Ebrahim 45). The implementation of tomboy traits upon the heroine and inclusion of action sequences could in part be due to the fears of Pixar executives that a princess narrative would deter its male audience. However, the film had a “gender-balanced audience” and performed well, receiving similar praise to Disney’s Frozen (2013) for seemingly offering a more realistic role model for younger audiences (Ebrahim 47). Arguably, Pixar’s first realistic female portrayal only came about three years later with Inside Out, and it was worth the wait.

According to Eliana Dockterman, “[w]hat’s so radical about Inside Out […] is that it’s about a normal girl with normal problems”. Riley is not a princess preoccupied with love and marriage, but a child on the brink of adolescence dealing with real life issues. The unique perspective offered by the bright humanoid characters representing her emotions provides great insight into her mind’s inner workings. The emotions reveal her concerns with moving to a new town, fitting in at school, and yes, a brief reference to an idealised boy in the boyfriend generator of Riley’s Imagination Land who announces, ‘I would die for Riley’. Though the emphasis is on the mundane and ordinary, the creative internalised perspective prevents the story from being dull. The film is much more than a tale about a young girl disliking her new home and deciding to run away; it is an introspective into the mental state of a person, not a princess. By employing the fantastic to convey the normal, Inside Out is able to universalise Riley’s concerns so as to resonate with both male and female children. As Shepard argues, having had princess narratives with unrealistic expectations and “anthropomorphized animals and objects” to discuss the pains of growing up, it was about time that children were given a protagonist in the same position as them (qtd. in Ebrahim 46). The film also encourages adults to reminisce on their own childhood and gives parents an insight into what their eleven-year-olds are going through.

Though Riley adheres to some tomboy characteristics in her love for hockey for example, her identity as a female character is not compromised. In fact, her physical appearance is not entirely acknowledged as “[h]er mind is the centrepiece, and we only get glimpses at what Riley actually looks like” (Dockterman). When we do see Riley she is often in jeans and trainers, has a no-maintenance hairstyle and doesn’t wear make-up like other girls in her class. As little attention is drawn to her outward appearance, Inside Out is able to tell the story of a girl without accentuating her femininity. She even has a unisex name that doesn’t gender her and enables everyone to connect to some aspect of her story as she is not represented in a limiting way. Docter has said that Riley’s varied interests are meant to create “a well-rounded, fleshed-out character” and this is even carried through to her five emotions (Stewart). Though her mother’s mind is composed of female emotions, and her father’s male, Riley’s mind is split. Joy, Sadness, and Disgust are portrayed as female, while Anger and Fear are animated to appear male. By incorporating emotions of both genders, the film-makers do not define Riley as a girl, but rather place her on a spectrum which is not specifically gendered in an attempt to create a genuine character that all audiences can identify with. As a result, Riley’s ordinariness differentiates her from Brave’s Merida because even though both aren’t overly feminised or stereotyped like Disney princesses, Riley’s experiences are rooted in the real world.

Though Riley is the main character in the classical sense, she shares her role as protagonist with two of her emotions, Joy and Sadness. According to a report by San Diego State University, “[o]nly 12% of protagonists and 30% of all major characters in the top 100 grossing movies of 2014 were women” (Dockterman). Inside Out serves as a stark contrast with not one, but three major female characters. Furthermore, there are two more secondary female characters in Disgust and Riley’s mother, outweighing the male characters with a total 5:3 ratio of female to male. Again, this contradicts the industry norm of having “only one female character for every three male characters in family films” (Dockterman).

In standard Pixar fashion, two opposing characters “embark on a psychological and/or physical journey together […] [and] their interaction is key to the characters’ growth” (Ebrahim 48). Though there have been many male-female pairs in this trend, notably, Marlin and Dory of Finding Nemo (2003), Joy and Sadness are the first female twosome. As they venture into Riley’s long-term memory, they succeed and grow in identical fashion to the male pairs in previous Pixar films. Like Carl and Russell in Up (2009), Joy and Sadness are complete opposites throughout their journey until Joy realises that Sadness is in fact her ally (Doo). The equality of the success of all of Pixar’s pairs, regardless of gender, again places sex in the background. As Dockterman notes, “Riley, Joy and Sadness are permitted to function in a universe where their gender doesn’t much matter” and this un-gendering of the film shows that Pixar are not afraid of going against the norm of female portrayal and setting the standard for other animated films.

Take her to the moon for me Inserting adult content into children’s films is not a new trend. For decades, film-makers, particularly animators, have found success in sneaking sexual innuendo and mature humour into family movies. DreamWorks, a competitor of Pixar, is known for creating such films. Their noteworthy pictures The Road to El Dorado (2000), Shrek (2001), and Kung Fu Panda (2008) all achieved great success through employing cheap laughs, adult humour, and, in the case of The Road to El Dorado, even a sly suggestion at characters partaking in oral sex. However, Pixar’s employment of adult content is slightly different. Rather than creating movies that are “held together by toilet humour and pop-culture references”, Pixar aims to discuss bigger, mature issues that “teach us something” (Weinman).

Since its debut with Toy Story (1995), “Pixar has shown an uncanny ability to talk about the pains and joys of growing up and ageing” (King 591). No issue is too serious or dark for the animators to confront and as the years have gone by, “Pixar films have moved toward bigger issues, even if they’re using robots and rats to make their points” (Weinman). The company has openly discussed the fear of being left behind (Toy Story), losing a loved one (Finding Nemo), fertility issues (Up) and an array of others. Though these complex “story choices may seem unusual now in an era where every other animated studio is doing comedies about wisecracking animals”, Pixar prides itself on placing commercial interest in a secondary role and “making a good movie first” (Huxley qtd. in Weinman). The decision to discuss the complex, and occasionally taboo, has consistently set Pixar apart from its rivals.

Reporter Rumy Doo observes that “[i]n recent years, large-scale animations that succeeded globally catered to both children and adults, with mature and layered plotlines”. There is no doubt that Inside Out, like all of Pixar’s previous productions, is layered with an “intricate plotline” with one of the subplots being Riley’s imaginary friend, Bing Bong (Doo). By bringing him to life, the film forces children to face the harsh reality that imaginary friends are only temporary. Older audiences are able to understand this concept whilst younger ones might not yet fully comprehend the notion that some of their friends are simply figments of their imagination. Yet, the film respects them by giving Bing Bong a life of his own and having him save Riley because he cares about her. In the scene of his sacrifice, he says to Joy, “take her to the moon for me, okay?”, before fading away into oblivion. The fact that one character can embody innocence, loneliness and growth highlights the complex layers to Inside Out. Bing Bong is aware that he is irrelevant now in Riley’s life and that he doesn’t have a place in her future. Leading up to his final moments, parts of his body become transparent, symbolising that Riley’s childhood is slipping away and he therefore represents the end of her childhood that she herself is conflicted about. To make a film about the pains of growing up is representative of reality because growing up isn’t always a smooth process and Pixar clearly do not shy from tackling difficulties.

By giving the “characters adult-like problems”, Pixar shows the respect they have for their audience’s intelligence (Weinman). Yet, there is a fine line between discussing bigger issues and breaching the depth of understanding of an adolescent mind and Pixar haven’t always been so successful in balancing the two. Ratatouille (2007) was the first Disney-Pixar collaboration, and “performed less well in North America than expected” as its lengthy running time and extended conversation on “food, art and creation” became “too complex for children” (Weinman). Having learned their lesson, Inside Out strikes a fine balance with its level of complexity and maintains an appropriate format for younger viewers. Running 94 minutes, much closer to the average Pixar film length of 99 minutes, the film is action-packed and creative, emphasising the imaginary and fantastic in a way that appeals to children while still maintaining serious undertones.

We can’t make Riley feel anything Inside Out “shows what’s happening – chemically – through the perspective of [Riley’s] emotions” (Godfrey). What neuroscientists understand as “the cerebral connections formed among a host of neurotransmitters”, the film-makers altered to five animated emotions running around inside the brain (Carroll 255). Discussing the chemical reactions of dopamine and serotonin in the brain would not have communicated well with children. However, portraying Joy as the captain of the control centre in the brain makes the situation understandable and conveys the same general idea. Though obviously not wholly accurate, Pixar’s representation of the functioning of the mind remained mostly precise.

During the three-year production process, Inside Out’s creators met with Dacher Keltner, a psychology professor at the University of California, Berkeley to understand “what makes people happy” (Godfrey). The film-makers wanted to realistically convey the inner workings of a child’s mind and emphasise those facets of the brain that are not widely known about. The most significant of these is sadness. Psychologists praised the prominence of the emotion in the film and clinical psychologist, Dr. Erica Chin, “was taken with the fact that the movie put in the position that sadness is OK and sadness is reasonable to feel” (Schonfeld). Though once incredibly taboo, the development of the psychology and a greater understanding of mental illness has increased awareness of sadness and its harsher cousin, depression, in today’s society and media. Now recognised as a chemical imbalance in the brain, it has become socially acceptable and understandable to not always have Joy at the helm of the mind. Child psychiatrist Kevin Kalikow explains that “[n]ot everybody is born with the same control panel. […] Some people are born happier. Some people are born more irritable” (Schonfeld). Such a variance is conveyed when the inner workings of other characters’ minds are revealed. Riley’s mother has Sadness in control of her mind, contrasting a school bus driver seen in the film’s credits who is shown to have five Angers dominating his mind. Furthermore, by placing different characters in control, Pixar references other formerly denounced mental issues, such as anxiety through Fear. The variety seen here emphasises that it is normal for people to be different and that sometimes feelings are inevitable.

A variety of films produced over the years have shown depression, including Girl, Interrupted (1999), Little Miss Sunshine (2006) and The Perks of Being a Wallflower (2012). However, “Inside Out is perhaps the only major motion picture ever to deal so directly with the inner workings of a child’s mind” (Schonfeld). In the film’s climactic scene where Riley runs away and the remaining three emotions are powerless to stop her, Anger states ‘we can’t make Riley feel anything’ which very clearly alludes to depression. Pixar’s bold address and normalisation of depression in children in a mainstream film is an unparalleled move. In addition, by showing Riley admitting her real feelings to her parents after she returns home, Inside Out highlights to children the importance of opening up to someone as being the first step towards getting better. Prior to release, there was much concern that a younger audience would not understand the complex material dealing with depression but a test screening quelled all fears as the company discovered that children were not confused by the film and that they “totally got it” (Miller).

This is partly a result of Inside Out’s production designers who intentionally based the visual structure of the film “on contrast between the outside real world and the inside mind world” (Lin). The “exterior” shots of Riley’s outer life were made to look real and imperfect, often embodying a duller colour scheme to represent Riley’s bleak outlook of the world. Where the happy memories in Minnesota are animated to be bright and colourful, the sequences in San Francisco are “construed in drabs and greys” (Miller). Meanwhile, the “interior” scenes are much more visually perfect, reflecting the bright colour of whichever emotion is currently in control. When Sadness begins to take over Riley’s mind, blue overwhelms the scenery. This symbolic tinting is especially predominant when Sadness turns numerous happy memories blue simply by touching the orbs. Dr. Chin explains that “[m]emories are not so concrete. [Pixar] did a good job of capturing that memories can be reframed”, especially when in a depressed mental state (Schonfeld). Such an honest portrayal of depression did not exist within the realm of family films until Inside Out.

Inside Out has not only contributed to an ongoing discussion surrounding mental health, it has also been embraced in contemporary culture. Through the “acute respect” shown to Sadness in the film, Pixar opened the door to even greater discussion of depression (Collin). Sadness was named one of Time Magazine’s “16 Most Influential Fictional Characters of 2015” for bringing “millions of viewers to tears”, and is “now being used as a teaching tool to help kids get in touch with their emotions” (D’Addario). Elisabeth Guthrie, a child psychiatrist at Columbia University Medical Centre, “plans to use the film in sessions with children”. Guthrie notes, “I thought it was helpful in putting feelings into words, for helping kids identify their feelings and start a dialogue about it” (qtd. in Schonfeld). Opening the door to discussion about emotions is likely the most successful attribute of the film, and of any of Pixar’s creations thus far because it ultimately taps into something common to everyone and concludes that all emotions are necessary.

Without doubt, Pixar’s 15th film, Inside Out, has struck a chord. The film reflects society’s desire for more realistic representations of females in films as well as the shift in contemporary culture whereby mental health problems are acknowledged and better understood. With such an honest take on the reality of growing up through the experience of an ordinary female protagonist yet to figure out her new identity, the film is able to resonate with all audiences. Overall, the film is very special and tender in how it represents the ‘little voices inside our heads’.

References

Carroll, V. Susan. “Taking a Look Inside.” Journal of Neuroscience Nursing 47.5 (2015): 255. Web. 5 Nov. 2015.

Collin, Robbie. “How Pixar found the secret of happiness.” The Telegraph. 29 Jun. 2015. Web. 5 Nov. 2015.

D’Addario, Daniel. “The 16 Most Influential Fictional Characters of 2015.” Time.com. 8 Dec. 2015. Web. 2 January 2016.

Dockterman, Eliana. “Why It Matters That Inside Out‘s Protagonist Is a Girl – Not a Princess.” Time.com. 22 Jun. 2015. Web. 2 Jan. 2016.

Doo, Rumy. “[Weekender] Target grown-ups — the recipe for hit animation films.” The Korea Herald. 4 Sept. 2015. Web. 5 Nov. 2015.

Ebrahim, Haseenah. “Are the “Boys” at Pixar Afraid of Little Girls?” Journal of Film & Video 66.3 (2014): 43-56. Web. 2 Jan. 2016.

Godfrey, Alex. “Pixar’s Pete Docter on the story (and science) of ‘Inside Out’.” WIRED Magazine. 20 Jul. 2015. Web. 5 Nov. 2015.

King, Joel. “Inside Out.” Australasian Psychiatry 23.5 (2015): 591. Web. 5 Nov. 2015.

Lin, Patrick. “The Ins and Outs of Inside Out’s Camera Structure.” International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques. Los Angeles Convention Center, Los Angeles, CA. 9 Aug. 2015. Lecture.

Miller, Lisa. “How Inside Out Director Pete Docter Went Inside the 11-Year-Old Mind.” Vulture. 16 Jun. 2015. Web. 5 Jan. 2016.

Schonfeld, Zach. “Inside Out: Pixar’s latest work of wonder depicts the inner workings of a child’s mind – so what do child psychiatrists make of it?” The Independent. 13 Jul. 2015. Web. 5 Nov. 2015.

Stein, Joel. “Pixar’s Girl Story.” Time.com. 5 Mar. 2012. 36-41. Web. 2 Jan. 2016.

Stewart, Sara. “’Inside Out’ is the powerful film little girls need.” New York Post. 13 Jun. 2015. Web. 24 Feb. 2017.

Terrero, Nina. “The mind-blowing success of Inside Out.” Entertainment Weekly. 24 Jun. 2015. Web. 5 Jan. 2016.

Weinman, Jaime. “The Problem With Pixar.” Maclean’s 121.26/27 (2008): 76-78. EBSCOhost. Web. 12 Nov. 2015.

Written by Jessica Lee Wilcox (2016); edited by Sladana Tegeltija (2017), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2017 Jessica Lee Wilcox/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post