Plot: Los Angeles, the present. Driver is a mechanic at a stock-car garage owned by his friend Shannon. He takes a phlegmatic approach to the two moonlighting jobs usually arranged for him by Shannon – doing stunts for movies and as a getaway driver for local robbers. Shannon has ambitions to set up a stock-car racing team utilising Driver’s skills; he negotiates for a sizeable loan from financier Rose, at the pizzeria run by Nino (real name Izzy), who is later revealed as a bitter and volatile would-be mafioso. Driver’s casual meetings with his neighbour Irene and her young son lead to a growing attachment to the pair and a motive for helping when Irene’s husband Standard, newly released from jail, is forced to take part in a raid on a pawnshop. The raid goes wrong and Standard is killed. After being chased by unidentified pursuers, Driver gets away with the bag containing a large amount of cash. Driver correctly guesses that it is drug money Driver intercepts one of Izzy’s henchmen tailing Irene; to her shock, he violently attacks him. Rose, in a separate incident, also reveals his violent capacities, spearing a fork into the eye of another of Izzy’s men. Driver tails Izzy’s car, forcing him off the coast road and drowning him in the sea. Realising that the money belongs to Rose, Driver arranges a meeting where the two fight and Rose dies (Hammond 2011).

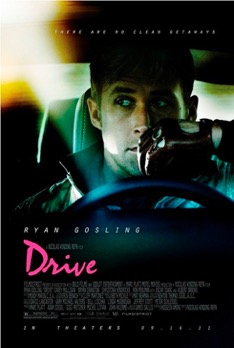

Film note Drive began life under the aegis of Universal Studios. In 2008, Universal allocated an adaptation of James Sallis’s pulp crime novel Drive a $60m budget. Neil Marshall was set to direct and Hugh Jackman was billed to play the lead. After two, silent years, however, Marc Platt took up the project, and Drive became wholly independent. In the end, the film was produced by a host of independent companies to the sum of $15m. Indeed, Platt’s intervention proved critical across the board. He convinced Ryan Gosling, by this time a rising star, to act in Drive’s central role. In turn, Gosling recruited Nicolas Winding Refn, who, as a Danish director at work mostly in Europe, was a relative unknown in the United States. Drive achieved commercial success and wholesale praise, taking $76.2m worldwide, a commendable yield of roughly 500 per cent, and won Refn the Best Director award at the Cannes Film Festival in 2011. Drive is multi-layered: its script bears the marks of multiple production studios and contrasting sensibilities and its aesthetic points towards aspects of independent film practice, though its narrative aligns it with mainstream genre film-making. In its form, history and content, it straddles popular cinema and the independent margins. The film note explores Drive’s palimpsestic nature, honing in especially on issues related to independent filmmaking and the film noir genre.

On Hollywood’s margin In Indiewood (2009), Geoff King analyses the intersections between Hollywood and US independent cinema. Centrally, King argues for an interstitial territory – “Indiewood” (2009, 1) – that is populated by the major studios’ specialist divisions, such as Fox Searchlight Pictures, and major productions that espouse an independent aesthetic whilst avoiding challenging, countercultural perspectives. As King notes, the attraction of these films stems from their ability to “crossover from niche to […] larger audiences” (2007, 59). They also do particularly well on the festival circuit, thereby garnering prestige for the studios. That said, independent companies also target Indiewood, and thus a wider mainstream market (2009, 9). In order to enhance their mainstream palatability, “indie [films] often [embrace] hybrid forms that draw on a number of different inheritances, including those associated with [independent practice] and more mainstream narrative feature traditions.” (2009, 9).

Drive’s narrative, form and style indexes the push-and-pull between independence and the mainstream. With this in mind, it is not unreasonable to suggest that Drive has been created with full awareness of the lucrative potential that comes with bridging the gap. For example, Drive incorporates various formal techniques indicative of an independent sensibility, such as the long, drawn out cinematography and static compositions of Slow Cinema; the rejection of spectacle, and the representation of action as an insular, implosive event typical of Ingmar Bergman’s work, as in The Virgin Spring (1960), and the use of editing practices that problematize narrative storytelling, such as jump cuts.

Towards the mainstream, Katerina Korola and Laura Shamas have noted how Drive’s narrative replicates the chivalric romance of high medieval poetry, with its characters falling in line with millennia old archetypes: a fact that renders Drive easily palatable to a majority of Western viewers. Drive’s marketing also reflects attempts to attract a mainstream audience. Arguably, the descriptions of Drive as ‘A Blood Pumping Thrill Ride’ that adorned its posters helped to package it as an action film, over and against a sparse independent production. As Korola and Shamas point out, this reading came to dominate; despite the film’s formal characteristics and its “explor[ation] of the medieval European concept of courtly love, [Drive] was widely reviewed as an action-thriller” (239).

Clutching hands, sadistic villains Ultimately, however, Drive’s mainstream appeal stems from its relationship to the noir genre. Though often an uneasy contention – Steve Neale laments that “nearly every crime thriller made in Hollywood is […] automatically labeled as noir or […] neo-noir” (309) – Drive certainly employs a host of noirish codes and conventions. Crucially, for example, it is an adaptation of a pulp crime novel. In terms of its basic elements, moreover, Drive is set on the streets of Los Angeles and low-level crime and corruption are a constitutive feature. Driver also becomes entangled with a married woman: a relationship that pushes him into a violent, downwards spiral. Additionally, at a thematic level Drive foregrounds masculine identity’s turbulent nature and the easiness with which sexual desire spills over into transgressive action.

Foster Hirsch notes that noir’s classification as a genre was retroactive, “applied first by […] French cineastes who [noticed a] dark tone in a group of American crime films released in France at the end of World War II” (2). Concerning its origin, Paul Schrader suggests that noir arose out of the tensions and anxieties concomitant with the troubles of the war and the wholesale disillusionment prevalent in popular culture in the United States after its end (54). Similarly, Jane Root points to the stagnation that surfaced after the plateau of the “1930s […] upwardly mobile thrust” (305). Evidently, then, the “clutching hands, […] sadistic villains, and heroines tormented with […] diseases of the mind” (305) that came to define the genre were a direct result of the concerns that wracked the United States in the post-war era.

Given noir’s historical specificity, the emergence of later films that espoused notably noirish sensibilities came to be classified as neo-noir. In Moving Targets and Black Widows, Leighton Grist outlined a taxonomy of neo-noir, boiling the subgenre down into three groups: modern, modernist and postmodern. Modern neo-noirs, such as Chinatown (1974), retain noir’s essential characteristics, though update its mise-en-scène into a modern environment. Modernist neo-noirs, like Taxi Driver, on the other hand, interrogate the “ideological assumptions” that underpin the noir genre (Grist 276). For Grist, this modernist reworking indexes wider ideological concerns, thus bearing a critical impetus. Conversely, postmodern neo-noirs, such as Blade Runner (1982), embody noir at an exclusively stylistic level, eschewing its critical potential. Replete with “references [that] are gestural rather than operative,” (275) postmodern neo-noir is characterised by a “self-conscious […] superficial[ity],” (272) or a “generic referen[tiality] that is not that of parody—which [defines] the reflexiveness of modernist noir—but pastiche” (272).

Arguably, Drive functions as a postmodern neo-noir. Its superficial-over-critical use of noirish themes, images and forms serves to render a modernist, countercultural force inoperative, helping to make its otherwise troubling content agreeable to the status quo and securing its status as an Indiewood text. In comparison with Taxi Driver, Drive’s postmodern divergence from neo-noir’s modernist branch is apparent. Taxi Driver is grounded in the social and political anxieties that gripped the US through the 1960s and 1970s. Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), Taxi Driver’s protagonist, is a Vietnam veteran who, upon returning to New York, struggles to navigate the city. Bickle’s disturbed, “baffled perception” (Hirsch 235) metaphorically cites the frayed nature of the nation’s social fabric after the Vietnam War. Drive, on the other hand, bears no relation to any particular historical context. The retro synth-pop soundtrack pulls it back and forwards in time, and its myriad array of cars – vital, foregrounded elements in the film – spans Ford’s 1955 Thunderbird, the 1968 Cadillac Fleetwood Eldorado and a 2011 Ford Mustang, amongst others. Unlike Taxi Driver, then, and indicative of postmodern neo-noir, Drive’s “setting, décor, and dress place the action in an indeterminate temporal realm,” (Grist 285) and destabilize one’s ability to link its mise-en-scène to any particular time period or ideological epoch.

Tellingly, Drive’s critical response was peppered with allusions to its relationship with noir and its nature as context-severed, eclectic pastiche. Mark Adams described Drive as a “magnificent homage to US crime films from the late 1970s and 1980s,” whilst conferring on its cinematography a “timeless quality.” Further, Sukhdev Sandhu called it a “masterpiece of surface over depth,” a “time collapse”; “retromania at its best – or at its self-conscious worst.” For Nigel Andrews, it was “all style and no soul.” Certainly, it is difficult to locate any critical agenda whatsoever in Drive. This effect is heightened by the fact that Driver, and the film as a whole, lacks a back story. Comparatively, in Taxi Driver, Bickle’s ultraviolent outbursts are rooted in his military past and function as necessary reactions to the wholesale corruption that has undermined the moral rectitude of Vietnam-era New York. Driver, on by contrast, is a nameless anti-hero without a past. Because of this, his extreme, calculated violence – stamping through an assailant’s head, inserting a pole into the throat of another – refuses to index any wider, extratextual issues, or the character’s constituent, psychological makeup.

Indeed, Refn has mentioned that he “wanted [Driver] to be […] an enigma […]” (Harris). In order to achieve this, “specific reasons [that underpinned] the way he was [were avoided] because then he would [have] los[t] his mythological qualities.” (Harris) This choice was in stark contrast to Sallis’s novel which took great care to undergird Driver’s character with a traumatic past. In this constellation, Driver’s exceptional violence does not possess a referent, thus retaining an unfathomable, enigmatic quality. Because of this, it functions as a superficial element and a feature of Drive’s style over-and-against a conduit of critique. This helps to render the violence acceptable, instead of repulsive. Given the thematic vacuum in which they occur, the violent scenes, all of which are predominantly shot in slow motion, are intended to be appreciated for how they look, not for what they are saying. Ultimately, then, Refn’s direct manipulation of Driver’s character serves to anaesthetise Drive’s most difficult content, repackaging sequences that might be expected to challenge the norm into a structure that enables them to be assimilated into general, mainstream circulation.

Bloodbaths and psychosis However, a claim can be made for Drive having some progressive qualities. Driver’s character is marked by an interchangeability between delicacy and brutality and in this the film breaks with the paradigmatic form of masculinity normally associated with film noir. This precarious duality is sustained through the intersecting features of Gosling’s star persona and acting style. Prior to Drive, Gosling was best known for romantic films, such as in The Notebook (2004) and Blue Valentine (2010). In terms of Drive’s diegesis, moreover, Driver personifies a non-conventional structure of noirish masculinity. For example, despite Driver’s simmering relationship to Irene, Drive features no sex and their relationship is restricted to quiet, intimate scenes in which Driver cares for both Irene and Benicio, her young son .This frames their romance as platonic and reflects Driver’s desire for commitment and family over-and-against sexual fulfilment. Indeed, Sacha Orenstein has pointed to these scenes as the moments through which Driver’s “saint-like compassion” is developed. Additionally, Shamas touched on Driver’s and Irene’s chaste romance as the vehicle through which Driver’s knightly persona is cemented, with “[t]he ardor of unconsummated passion [underscoring] the devotion of [Driver’s] altruistic service.” (240) To be sure, Driver kisses Irene only after Standard’s death and thus Irene’s symbolic divorce.

Going further, Drive does not possess a sexualised, noirish femme fatale archetype, which is the central character around which most noirs spin. Rather, it features the femme fatale’s stock antithesis, which is the homely, “domesticating woman who […] threat[ens] the male protagonist” (Neale 310) with her unmanly impulse. However, the fact that Driver achieves masculine fulfilment through Irene – he confidently kills to defend and protect her – troubles her archetypal role as emasculating. It also highlights Driver’s constituent effeminacy. Irene’s arrival does not sunder his masculinity because his masculinity is malleable and fluid; it already holds the potential for delicacy, domesticity and effeminacy.

Evidently, questions of masculine identity are at the heart of Drive. Typical of film noir, it represents a masculinity that strides between romantic desire, “psychotic action, and suicidal impulse” (Martin 81). Mirroring Taxi Driver, Driver’s psychotic deterioration into savage action occurs during its violent sequences. However, a central difference separates the two representations. In Taxi Driver, the closing violent sequence is set in motion by the female protagonist, Iris (Jodie Foster). In Drive, on the other hand, the violent sequences are mobilised by men, thus destablising the noir woman’s canonical function as the catalyst of male destruction. Regarding Taxi Driver, moreover, Hirsch suggests that Travis, in his inability to achieve intercourse with a woman, finds sexual fulfilment in Taxi Driver’s iconic shootout, or “orgasmic bloodbath” (236), thereby grounding his aggression in his isolation from, and distance to, women. In Drive, conversely, Driver, upon realising that Irene is under threat, passionately kisses her and seizes her assailant before killing him by stamping through his head. Here, the violent act collapses the distance between Driver and Irene, bringing them closer and thus destabilizing the negative relationship between men, women and violence in film noir.

Ultimately, this serves to sever the negative link between women and psychotic masculine violence in film noir. In this sense, Drive repositions noirish masculinity and femininity along a more progressive line. Indeed, Gosling’s diegetic descent into psychotic action does not wholly stem from sexual frustration, or the presence of a corrupting femme fatale. As a star, moreover, Gosling does not fulfil a masculine archetype, though he does overcome a host of distinctly masculine characters through sheer, unbridled aggression. In other words, Gosling’s ‘effeminate’ brand of masculinity outstrips that of Bernie and Nino, Drive’s dominant gangster figures and the fictional counterparts of the more stereotypically masculine Albert Brooks and Ron Perlman, respectively.

That said, Drive’s progressivism is undermined by its refusal to offer a bold, fully-fleshed countercultural message, its tendency towards superficiality and its concessions to the mainstream. In this, it fits within a wider cycle that includes Looper (2012), a film that blends science fiction, noir and crime thriller elements, Brick (2005), a pastiche ridden, teenage view on the noirish detective caper, Safety Not Guaranteed (2012), a contemporary revision of the hopeful science fiction films of the 1980s, and Sin City (2005), an ultra-stylish, patchwork amalgam unified by its noirish overtones. With Looper garnering $176.5m worldwide, Sin City $158.8m and Brick $3.9m from a budget of $500,000, the benefits that come with crossing over are plain to see. Undoubtedly, however, Hollywood has also harvested the rewards that come with appealing to the independent sphere. Certainly, with firm successes in Juno (2007) and (500) Days of Summer (2009), and with The Silver Linings Playbook (2012) and Django Unchained (2012) on the horizon, this trend looks healthy and shows no signs of stopping.

References

Adams, Mark. “Drive.” Screen Daily. 20 May 2011. Web. 20 Jan. 2019.

Andrews, Nigel. “Drive.” Financial Times. 22 Sep. 2011. Web. 20 Jan. 2019.

French, Philip. “Silver Linings Playbook – Review.” The Observer. 25 Nov. 2012. Web. 20 Jan. 2019.

Grist, Leighton. “Moving Targets and Black Widows: Film Noir in Modern Hollywood.” The Movie Book of Film Noir. Ed. Ian Cameron. London: Studio Vista, 1992. 267-285. Print.

Hammond, Wally. “Film review: Drive.” Sight and Sound, 21.10 (2011): 60-61. Print.

Harris, Brandon. “Nicolas Winding Refn, Drive.” Filmmaker Magazine. 14 Sep. 2011. Web. 6 Dec. 2012.

Hirsch, Foster. Detours and Lost Highways: A Map of Neo-Noir. New York: Limelight Editions, 1999. Print.

King, Geoff. Indiewood, USA: Where Hollywood Meets Independent Cinema. New York: I.B. Tauris, 2009. Print.

King, Geoff. “The Major Independents.” The Cinema Book, 3rd edition. Ed. Pam Cook. London: British Film Institute, 2007. 54-60. Print.

Korola, Katerina. “The Driver Errant: A Critical Evaluation of Drive and “New” Masculinity.” Offscreen, vol. 17, no. 3, 2013. Web. 16 Jan. 2019.

Martin, Richard. Mean Streets and Raging Bulls: The Legacy of Film Noir in Contemporary American Cinema. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 1997. Print.

Neale, Steve. “Noir and Neo-Noir.” The Cinema Book, 3rd edition. Ed. Pam Cook. London: British Film Institute, 2007. 309-315. Print.

Orenstein, Sacha. “The Gangster Archetypes of Nicholas Refn.” Offscreen, vol. 17, no. 3, 2013. Web. 16 Jan. 2019.

Root, Jane. “Film Noir.” The Cinema Book, 3rd edition. Ed. Pam Cook. London: British Film Institute, 2007. 305-308. Print.

Sallis, James. Drive. Scottsdale, AZ: Poisoned Pen Press, 2005. Print.

Sandhu, Sukhdev. “Drive, review.” The Telegraph. 30 Oct. 2014. Web. 19 Jan. 2019.

Schrader, Paul. “Notes on Film Noir.” Film Noir Reader. Ed. Alain Silver & James Ursini. Newark, New Jersey: Limelight Editions, 1996. Print.

Shamas, Laura. “Film Review: Drive (2011).” Psychological Perspectives, 56.2 (2013): 239-242. Print.

Quick, Matthew. The Silver Linings Playbook. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008. Print.

Written by Elisabeth Kate Marks (2013), edited by Christian Dymond (2019), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2013 Elisabeth Kate Marks/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post