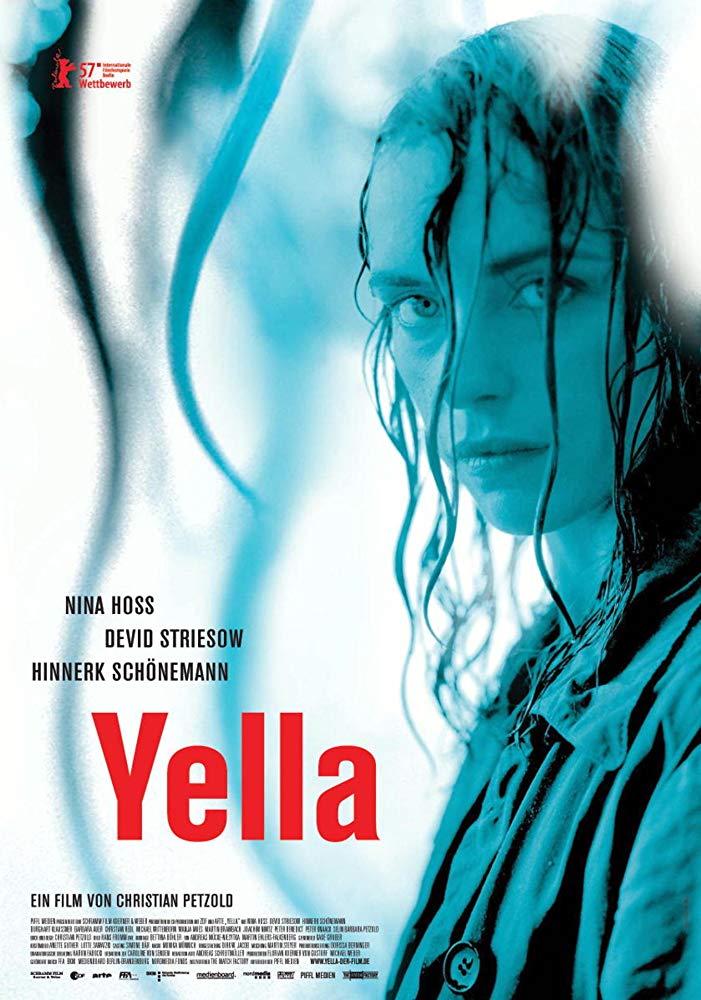

Plot Wittenberge, 2000s. Yella, a young businesswoman, flees her East German hometown in order to secure a job in West Germany. Before she can depart for Hannover, her obsessive ex-husband Ben drives them both off a bridge, but she survives the crash. Once she reaches West Germany, her dreams of a fresh start are broken as she realises that the company for which she works as an accountant is bankrupt and her boss sexually harasses her. Philipp, a young executive Yella meets at her hotel, offers her a job as his assistant. During a series of tense business deals, Yella discovers that she is a capable player in the ruthless world of private equity and develops a strong friendship with Philipp. Yella’s past comes back to haunt her in the form of the violent Ben, as well as through the experience of nightmarish visions. After Philipp loses his job, the most explicitly supernatural vision happens when Yella blackmails one of the business executives her and Philipp had previously dealt with. Yella sees a ghostly image of the executive soaked in water, and later finds out that he drowned himself due to her threats. As the police arrest her, it is revealed that the visions were echoes of her own death, which had in fact occurred the moment Ben drove their car into a river near the beginning of the film.

Film note Yella stands in stark contrast to what Eric Rentschler described as the “German Cinema of Consensus”. In his fervent article on the topic, Rentschler notes that the death of Rainer Werner Fassbinder in 1982 symbolised, in Germany, the dissolution of an individualised auteur cinema in favour of films that have “a much lighter touch and are more user-friendly” (264). In the early 2000s, however, a movement known as the Berlin School returned to personalised filmmaking in a challenge to the Hollywood-oriented German mainstream. Christian Petzold is, indeed, a leading figure in the movement. His feature Yella displays an individual style, challenges mainstream notions of genre and has echoes of the subversive, politicised films of New German Cinema filmmakers such as Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

Insight and sound Against a backdrop of genre films such as The Most Desirable Man (Der Bewegte Mann, 1994) or The Lives of Others (Das Leben Der Anderen, 2006), which are indicative of Rentschler’s concerns about cinema as a “site of mass diversion” (264), the Berlin School is able to provide German cinema with filmmakers capable of “formal and stylistic ambition” (Fisher and Prager 6). This work is similar to that of stands against the standardisation of the commercial cinema. Petzold exhibits a highly reserved, meditative tone, which contrasts the sensationalism of the mainstream. Yella provides a useful example of this tone with its controlled pacing and “acute sensitivity to place and space” (Darke), both of which serve to provide the viewer with room for reflection.

One particular scene involves Philipp (Devid Striesow) lashing out at Yella (Nina Hoss) for diverting their car journey so she could visit her hometown of Wittenberge. After a distressed Yella scurries away from Philipp, a medium long-shot frames her against the muted greenery of the rural environment. Afterwards, the camera cuts to a vast wide-shot of the menacing landscape surrounding the character, symbolising the weight of the past that haunts her solitary existence. Petzold used a similar technique in Ghosts (Gespenster, 2005), where the loneliness of Nina (Julia Hummer) is highlighted by her standing in the middle of a long-shot rigorously framed by two rigid, brown door frames that confine her in an empty, red-lit party room. To Petzold, the use of space and environment is particularly useful to visualise the repressed emotions of his characters.

Another atmospheric element found in Yella is its sterile colour palette, where the protagonist’s red blouse is often the only source of brightness. For instance, when Yella first enters the office of her future boss, she finds herself surrounded by dull blacks and steely silvers, which reflect the insipidity of corporate Germany. Again, Petzold employs a similar use of colour in Ghosts, in a scene where Nina dances in the aforementioned artificially lit, lurid red party room. The shot of her dancing is intercut with a shot of Oliver (Benno Fürmann) standing outside the room surrounded by plain colours, which signify the bleakness of the reality outside.

Petzold often relies on techniques typical to various Berlin School graduates such as “precisely framed shots [and] long takes” (Abel 2010, 263). Although he does not employ long takes as much as other exponents of the movement such as Angela Schanelec, his shots tend to linger to encourage the viewer to engage in contemplation. Petzold manages to capture Yella’s loneliness and frustration through an eighty seconds long take depicting her attempt to call an unresponsive train company’s phone. When the attempt fails, the irritated Yella hangs up and turns her haunted eyes towards the camera. A static and tightly framed shot lingers on her stony expression as she fiddles with her hands and slowly slips on her shoes. Her countenance, bodily gestures and silence are all captured in an uninterrupted take that serves to deepen the emotional understanding of the character’s struggle.

Another one of Petzold’s auteurist traits is his idiosyncratic use of sound design. Unlike the mainstream industry, where sound is mostly used as a tool to heighten the emotional impact of a scene, Petzold refrains from auditory excess. Petzold uses sound similarly to other auteurs directors such as Michael Haneke and Apichatpong Weerasethakul, who highlight diegetic, everyday sounds in order to add weight to them. Indeed, Yella opens with the sharp sound of a train’s wheels, which catches viewers by surprise by cutting off the opening credits’ silence and throwing them into Yella’s monotonous world. Later, after Ben (Hinnerk Schönermann) drives their car off a bridge and Yella emerges from the river’s water, the soundtrack is permeated with loud sounds of trees rustling, water running and crows cawing. By shifting and overlapping one another, these sounds acquire an ominous tone and serve as auditory expressions of the character’s interiority. This approach differs from a mainstream one in that it does not require non-diegetic music to force emotion upon viewers, but rather encourages them to engage independently with the character’s own interiority and surroundings.

Other than sounds, “silence and inscrutability seem to predominate” (Fisher 190) Petzold’s films, particularly within the actors’ performances. In an interview, Petzold described Nina Hoss as an actress who “empties herself” creating emotional distance between character and audience. Allan Casebier describes this distance as forcing viewers to “contemplate the characters’ actions” (111). In Yella’s opening scene, whilst Ben verbally harasses the protagonist, her expression remains stony and her eyes remain cast to the ground, with the exception of occasional glances towards the harasser. Her silence and austerity effectively convey the character’s vexed mood. Here one can find another parallel with Ghosts: after Nina finds herself abandoned by the film’s co-protagonist, Toni (Sabine Timoteo), she embarks on a train ride during which she maintains a plain, unrevealing expression. It is through their knowledge of Toni’s deception that viewers are able to project emotion on Nina’s aloof attitude.

A different kind of horror Despite his non-conformist attitude towards the mainstream, Petzold harbours a deep interest in popular genre cinema reminiscent of Fassbinder’s love for Sirkian melodramas. Petzold blames the German Autorenkino for creating a divide between genre and art-house cinema (Abel 2008), and advocates for a communion between the two. However, he is able to rewrite genre conventions to elevate them beyond their commercial value. Fassbinder held a similar stance, advocating a union between the aesthetics of Hollywood and “a critique of the status quo” (Gemunden 89). Therefore, a comparison between the two auteurs proves particularly useful in analysing how Yella deconstructs genre conventions and imbues them with political gravitas. In particular, Yella presents distinct elements of the horror genre, which can be seen as an allusion to cult horrors such as Hank Harvey’s Carnival of Souls (1962). Similarly, an example of Fassbinder’s interest in melodrama is his feature Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (Angst essen Seele auf, 1974), which is an homage to Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955). As Jaimey Fisher phrases it, both Yella and Ali operate as a “refunctioning” of genre form.

Fassbinder’s “anti-melodramas” are able to create “an aesthetic distance between the film text and the viewer, [leading] the viewer to recognise the film as a specifically cinematic act […] and thus actively to analyse [it]” (Woodward 586). By eschewing extreme feelings of sadness or joy, Ali’s conclusion leaves the viewer “contemplating how political and emotional realities intertwine” (587). Whereas at the end of All That Heaven Allows the two protagonists’ reconciliation ends on an optimistic note, Ali’s (El Hedi ben Salem) reconciliation with Emmi (Brigitte Mira) is hindered by his status as a foreign worker and his contraction of a life-threatening ulcer. Similarly, Yella creates “critical distance [by] inviting self-reflection on the mechanisms of the artwork” (Fisher 197). The film is laced with horror genre tropes, as evidenced by a scene in which, after Yella enters a previously locked hotel room, Ben mysteriously materialises in a darkened corner of said room. Petzold raises awareness in viewers of the impossibility of such moments, thereby highlighting the artificiality of escapist genre films.

Unlike conventional horrors, Yella lacks the presence of a “stabilising […] socially vested figure” (Fisher 197-98) such as the helpful doctor in Carnival of Souls. Although initially, as Fisher notes, Philipp “seems to serve such a function” (198), later in the film he turns hostile. As his character shifts from being reminiscent of Yella’s loving father to mirroring the violent Ben, the film makes it clear that the protagonist’s reality is imperfect and she cannot escape her past. By creating ambiguous, morally complex characters, Petzold is able to deconstruct the feigned morality of conventional genre films, which are characterised by “a clear dichotomy between good and evil” (Woodward 589). The protagonist of Ali is both the innocent victim of xenophobic abuse and a morally flawed individual due to his involvement in an adulterous relationship. Similarly, in Yella, the viewer’s sympathies towards the protagonist are challenged as she becomes gradually corrupted by the German capitalist system and grows thirsty for money. By the end of the film, she attempts to wring money from a former client in order to further her and Philipp’s own interests. By depriving the viewers of conventional genre’s ethical polarity, both Ali and Yella force them to confront humanity’s, and indeed their own, moral complexities.

Ultimately, Petzold’s and Fassbinder’s outlooks on morality allow them to transpose classical genres to an array of contemporary social issues. In Ali, Fassbinder replaces the theme of class in All That Heaven Allows with a focus on race, implying that “National Socialism has become part of lower-middle-class thinking” (Thomsen 140). When Ali meet’s Emmi’s family, a tracking shot captures their shocked, disgusted expressions, signifying the indelible marks left on the country by Nazi racial policies. In Yella, Petzold “seems to deploy a body genre [to show how] contemporary capitalism denatures and recolonizes bodily sensation and desire” (Fisher 194), thus offering a critique of contemporary, capitalist Germany through classical horror genre tropes. Beyond the thematic signifiers and genre tropes that pervade Yella’s locations and mise-en-scène, the choices to film near the site of the Expo 2000 and have the money-driven characters ride in Mercedes taxis highlight Petzold’s socio-political focus.

Don’t tear down this wall Similarly to how New German Cinema directors raised “serious questions about the past and West German reconstruction”, the works of the Berlin School have “cast a critical eye on Germany’s past and present” (Fisher and Prager 11). The political elements of Berlin School films, which stand against the mainstream’s varnished Hollywood aesthetics, often serve to examine how “post-wall Germany has reconnected with the world in the wrong ways” (Moller). Ekkehard Knorer describes Petzold as “the most openly political of the group”, which is perhaps due to the influence of his mentor Harun Farocki, an overtly political filmmaker. A critique of contemporary, neoliberal Germany and the consequences of the country’s past lies at the heart of some of Petzold’s key themes such as the “ghostlike spaces” (Abel 2008) inhabited by characters that want to escape them.

Another one of such themes is mobility. Marco Abel argues that German presidents like Roman Herzog and Horst Kohler encouraged citizens to “embrace neoliberal ideas of mobility” (2008). Petzold’s depiction of mobility is, paradoxically, static: throughout the many scenes where the characters in Yella travel by car or train, the framing is largely stiff and fixed to their faces. During these moments, the confirmation of transformation and change of these characters “occurs from within […] on a haptic level” (Abel 2008). Additionally, despite the protagonists being constantly on the move to achieve their ambitions, all they reach is emotional instability, which shows mobility to be a façade. Petzold uses a similar technique in Ghosts, in a scene where Pierre (Aurélien Recoing) drives with Nina down a motorway. Despite the expensive car he drives and the relaxing musical soundtrack, the camera stays fixed on the back of the character’s head, highlighting his internal struggles, which contrast the luxurious external environment.

Petzold’s oeuvre intertwines concerns surrounding the present state of Germany with meditations on the “lingering consequences of the past” (Abel 2008). Yella works as an allegory of the alienating effects of the post-Wall period. The effects of capitalism on East German citizens, particularly women, created an “increase in loneliness [and] unemployment” (Kaplan 374), as they struggled for economic independence. Yella’s desire to move forward is constantly hindered by her yearning to return to her East German hometown. Philipp, who symbolises her ambitious drive towards economic independence, lashes out on her when she diverts their car journey to visit Wittenberge. Furthermore, other than its effects on individuals, the reunification also affects traditional notions of family. Germany has “fallen victim to capitalist imperatives”, urging its citizens to be “mobile, individual and workaholics” (Abel 2008). The cultural importance of family communion was therefore hindered by capitalism, as German films of the 1990s effectively expressed by portraying Berlin as an “alienating environment” (Clarke 177). Yella’s father, despite being compassionate and supportive, cannot keep her from abandoning him to follow her ambitions. Instead, he attempts to provide her with economic support for her journey. However, Yella refuses his money, stressing the importance that capitalist society places on the individual’s need for absolute independence against the idea of mutual familial support.

In conclusion, Yella’s political tensions represent yet another element through which Petzold, as a Berlin School member, positions himself against the mainstream industry. Rentschler’s longing for the formal intelligence and themes of New German Cinema is perhaps justified by the overwhelming influence of the “cinema of consensus” on the industry. However, Berlin School auteurs are still capable of pursuing unconventional aesthetics, individual outlooks and socio-political commentary. By both echoing Fassbinder and displaying an individual style, Petzold adopts the role of a dissident figure able to enlighten contemporary audiences, an attitude of which Yella is a prime example.

References

Abel, Marco. “The Cinema of Identification Gets On My Nerves: An Interview with Christian Petzold” Cineaste 33.3 (2008). Web. 19 Feb 2019.

Abel, Marco. “Imagining Germany: The (Political) Cinema of Christian Petzold” The Collapse of the Conventional: German Film and Its Politics at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Eds. J. Fisher and B. Prager. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010. 258-284. Print.

Casebier, Allan. Film and Phenomenology: Towards A Realist Theory of Cinematic Representation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. Print.

Clarke, David. “In Search of Home: Filming post-unification Berlin” German Cinema: Since Unification (New Germany In Context), Ed. D. Darke. London: Continuum International, 2006. 151-180. Print.

Darke, Chris. “Review: Yella” Film Society of Lincoln Center. May/Jun. 2008. Web. 19 Feb. 2019.

Fisher, Jaimey and Prager, Brad. “Introduction” The Collapse of the Conventional: German Film and Its Politics at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Eds. J. Fisher. and B. Prager. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010. 1-28. Print.

Fisher, Jaimey. “German Autoren dialogue with Hollywood? Refunctioning the horror genre in Christian Petzold’s Yella (2007)” New Directions in German Cinema, Eds. P. Cooke. and C. Homewood. London: I.B. Tauris, 2011. 186-203. Print.

Gemunden, Gerd. Framed Visions: Popular Culture, Americanisation and the Contemporary German and Austrian Imagination. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998. Print.

Kaplan, Gisela. “Development: Western Europe” Routledge International Encyclopaedia of Women: Global Women’s Issues and Knowledge. Ed. C. Kramarae and D. Spender. London: Routledge, 2000. Print.

Knorer, Ekkehard “Luminous Days: Notes on the New German Cinema” Vertigo Magazine 3.5. Spring 2007. Web. 19 Feb 2019.

Moller, Olaf. “Vanishing Point”. Sight and Sound. October 2007. Web. 19 Feb 2019.

Rentschler, Eric. “From New German Cinema To The Post-Wall Cinema of Consensus” Cinema and Nation. Eds. M. Hjot and S. Mackenzie. London: Routledge, 2000. 260-277. Print.

Thomsen, Christian Braad. Fassbinder: The Life and Work of a Provocative Genius London: Faber & Faber, 1997. Print.

Wood, Jason. “Interview with Christian Petzold: Many Rivers To Cross”. Sight and Sound. October 2007. Web. 19 Feb 2019.

Woodward, Katherine S. “European Anti-Melodrama: Godard, Truffaut and Fassbinder” Imitations of Life: A Reader on Film and Television Melodrama (1991): 586-595. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. Print.

Written by Keifer Nyron Taylor (2013); Edited by Francesco Quario (2019), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © Keifer Nyron Taylor 2013/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post