Plot Markos Dance Academy, Berlin, 1977. American dancer Susie travels to Berlin to audition for the Markos Dance Academy. Meanwhile, academy student Patricia disappears after revealing to her therapist Dr. Klemperer her suspicions that the academy’s matrons practice witchcraft. Upon her arrival Susie is noticed by Madame Blanc, the academy’s artistic director, and when Olga, the academy’s lead dancer, confronts Blanc about Patricia’s disappearance, Susie offers to perform Patricia’s part, under a spell casted by Blanc, that turns her movements into violent strikes against trapped Patricia. Her powerful performance attracts the attention of Helena Markos, the academy’s diseased leader (claiming to be mother Suspiriorum), who is in search of a new body vessel. Markos commands Blanc to prepare Susie for the body-offering ritual, and Susie becomes the lead dancer of the academy’s Volk performance. Meanwhile Klemperer asks dance student Sara to help him learn more about the academy. Sara discovers a secret corridor to the academy’s catacombs where rituals take place. The night of the Volk Sara goes back, only to find a semi-alive Patricia, before she is discovered by the matrons. Hypnotized she is dragged on the stage where she finally collapses before the eyes of Klemperer. The Volk ends, and the troupe go out to celebrate. Klemperer is walking home, when he encounters his lost wife Anke. The two are strangely led back to the academy, where Anke vanishes. The matrons are there, and captivate Klemperer. Susie is led to the academy’s catacombs. The matrons, Markos, Klemperer, and the academy’s hypnotized dancers are there for the ritual. Susie announces that she is ready, and Markos asks her to renounce any ‘other mother’ before offering her body. Susie summons Death, and upon revealing she is the true Mother Suspiriorum, she commands Death to kill Markos and her followers. The following day nobody recalls the events but Susie, the matrons and Klemperer. Susie visits Klemperer to apologize for the torment he underwent, and erases his memory. In a post-credit scene Susie is staring at something off-screen, and then walks away.

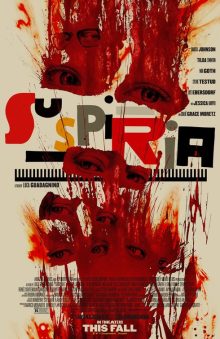

Film Note: Directed by acclaimed director Luca Guadagnino, Suspiria (2018) is a contemporary remake of Dario Argento’s cult thriller Suspiria (1977). The film was funded by Amazon Studios, marking the Studio’s first attempt to enter the realm of horror. Suspiria (2018) reimagines the original’s geopolitical context, situating its narrative present in the year of the original’s release, namely 1977. In the essay that follows, Suspiria (2018) will be examined in relation to its industrial context, feminist psychoanalysis and the subversion of the witch archetype, and Suspiria’s political implications about division in the US society.

Remaking Suspiria Discussions around the possibility of a Suspiria remake began in 2008, after director David Gordon Green announced that he would undertake the project, having co-written an ‘operatic’ script with sound designer, Chris Gebert. However, after ‘running into legal trouble’ (Jagernauth) Green’s remake of Suspiria was called off, with the director expressing his hope that it would still be made ‘with a great Italian director’, whose name would be revealed during the 72nd Venice Film Festival. Alongside the premiere of his film A Bigger Splash (2015), director Luca Guadagnino announced his plan to remake Suspiria, not as a faithful recreation of Dario Argento’s 1977 original, but as an ‘homage to the incredible, powerful emotion’ that he felt when he first watched the film (Guadagnino in Mumford).

Guadagnino’s Suspiria, co-written with scriptwriter David Kajganich,was produced by US independent production companies K Period Media and Mythology Entertainment, Guadagnino’s Italian production company Frenesy Film, as well as Amazon Studios, thus providing an opportunity for Amazon to take their first step into the realm of the horror genre, while profiting from the commercial safety of a remake. As Verevis discusses in his book Film Remakes, remakes of original pre-loved films function as ‘commercial products that repeat successful formulas in order to minimize risk’ thereby offering studios the ability to ‘secure profits in the marketplace (37). Additionally, the current tendency in US horror film production to remake domestic and foreign films from the 1930s to the 2000s, with producers often strategically avoiding allusions to the films’ remake nature in titles or trailers, ‘enables studios to package them as completely new releases’ while capitalizing on their prior success (Francis, 3). James Francis explains that the horror remake’s commercial promise relies on its ability to ‘present fear anew with star power, directorial style, and memory of what scared audiences in the past’ (5). This design can be seen in the bringing together of Guadagnino’s innovative directorial style, Tilda Swinton and Dakota Johnson’s acclaimed talent, and the original Suspiria’s ‘classic or cult’ status. This offered a unique opportunity for Amazon Studios not only to respond to an increasing demand for cult horror remakes, but also to join its rival, Netflix, in the competition for Academy Awards, as part of the company’s strategy to attract top filmmakers and ‘projects that, in turn, will lure subscribers’ (Kilday).

While Suspiria (2018) retained a European ‘air’, with most of its footage being produced in Italy, as well as by using the 77’ German Autumn’ as its reimagined socio-political background, it would be hard to call it a ‘foreign’ or European film. Suspiria’s (2018) main talents are either American (Johnson, Moretz, Harper) or British (Swinton, Goth), its soundtrack is composed by British musician, and Radiohead’s main vocalist Thom Yorke, and its production was chiefly financed by Amazon, making the film primarily directed towards American audiences. While the film utilised elements of a European context, its effort to appeal to English-speaking culture, makes it appear closer to what Verevis describes as an ‘American remake of foreign film’ (11), ‘aiming to exploit new English-language markets’ (3).

In April 2018 one of the film’s most violent and gruesome sequences was chosen by Amazon and Guadagnino to debut in the Las Vegas CinemaCon, in a room filled with awed and horrified ‘cinema owners and studio executives’ (Lang). The scene featured Susie (Johnson) performing a choreography, affecting with every one of her movements the body of another dancer, ultimately disassembling her limbs and killing her. The sequence’s projection sparked controversial reactions on Twitter, with users describing it as traumatizing and unnecessarily violent, discouraging viewers from watching the film, while others were intrigued by the scene’s extreme gore, expressing their ‘need to see more’ (Weintraub, Twitter). In June 2018, the MPAA (Motion Picture Association of America) gave the film an R rating, for ‘ritualistic violence, bloody images, graphic nudity, and for some language including sexual references’, a rating that was anticipated by Amazon Studios, as it reinforced the status of the studio’s first horror film. In a humorous tweet showing the MPAA’s R rated template, Amazon Studios added ‘This is accurate’, proudly drawing attention to the film’s promise of blood and violence.

Suspiria debuted at the 75th Venice Film Festival, and became available for limited release in Los Angeles and New York on the 26th of October, where it led the highest screen-average box office launch of the year earning ‘just over $180,000 in two theaters for an average of $92,019 per screen’ (Strowbridge). Upon wider, yet still relatively limited, release in the US and internationally, the film did not receive the same success, earning a worldwide total of $7m with a production budget of $20m. While Guadagnino’s initial vision included a sequel to Suspiria, exploring the life of Helena Markos ‘being a charlatan woman in the year 1200 in Scotland’ (Guadagnino in Encinias) such a possibility was rendered impossible, as the film did not perform well enough at the box office.

The film’s commercial performance could be partially attributed to the legal dispute Suspiria was involved in, as Amazon Studios were sued by the Estate of Ana Mendieta after ‘images that were derived from Mendieta’s work’ (Maddaus) were found in the film’s trailer without the authorization of the estate. Amazon had to remove the film’s first official trailer, as well as further images from the film featured in Susie’s dream sequences, as they bore suspicious similarity to the Cuban-American artist’s work. The film’s accusations of appropriation, and entanglement in a legal dispute, may have disrupted its marketing strategy, ultimately reducing its commercial potential.

Despite the weak performance of the film at the box office, Suspiria is still available for viewers through Amazon’s streaming platform, Prime Video, together with Argento’s original. However, it is not one of the first options suggested by the service when one searches for horror, or thriller films. While the film was not a commercial success, and has only received 408 global reviews on Prime Video, in contrast to Suspiria’s (1977)1852, or Call Me By Your Name’s (2017) 7386 reviews, implying a rather low performance on the platform, one could support that it paved the way for Amazon Studios in their exploration of the horror genre, as they proceeded to produce seven original horror films during 2020 and 2021, making up 15% of Amazon Studio’s total of 53 film productions for those two years.

Reinventing the Witch In her essay Power of Horror (1982) Julia Kristeva elaborates on a term she uses to discuss a particular existential anguish one experiences when confronting ‘the border of [one’s] condition as a living being’ (3). Through her use of the term ‘abject’, Kristeva refers to literary depictions of bodily fluids such as blood, pus, and sweat, as well as visual signifiers of death and decay, such as corpses and bodily parts, explaining that such images cause abjection as they reveal the permeable physicality of the human body, thus alluding to its mortality. Kristeva’s essay on the abject in horror literature, was later used by Barbara Creed, as a starting point to explore cinematic horror through the same lens. In her book The Monstrous Feminine (1993), Creed utilizes Kristeva’s descriptions of the ‘abject’, as well as Freudian psychoanalytic theory, in order to demonstrate the tropes used in the horror genre to depict woman as monstrous, ascribing the monstrous female’s abject nature to her ability to castrate either literally or metaphorically. In her exploration of female monstrosity, Creed explicitly refers to the witch archetype, explaining that one of the prominent features of the witch ‘in earlier centuries was her role as healer’ (74), a positive role which was however removed from contemporary portrayals, after the prevalence of the witch figure in ‘the 1960s [when she] joined the ranks of popular horror film monsters’ (73). In Creed’s words the witch figure was usually depicted as an ‘old, ugly crone’ (72) ‘represented within patriarchal discourses as an implacable enemy of the symbolic order’ (76), who needed to be expelled as part of films’ moral restoration. Discussing Suspiria (1977) Creed elaborates on the film’s stereotypical representation of Mother Suspiriorum, as ‘a grotesque, monstrous, completely hideous figure’ (76), and critiques the film’s lack of exploration of the witches’ purpose, making them appear as existing with the ‘sole purpose […] to wreak havoc and destruction in the world’ (76). Despite Guadagnino’s adoption of a similar narrative spine to Suspiria (1977), Suspiria (2018) actively subverts expectations associated with female monstrosity, by creating two different dynamics amongst the witch characters, consequently commenting on their moral integrity, rather than their female nature or innate ‘abjectness’.

While one could argue that Suspiria (2018) ultimately offers a feminist re-evaluation of the witch figure, it would be rather naive to completely deny the film’s reliance on stereotypical tropes. A sequence that demonstrates the prevalence of these tropes, is the one when Miss Tanner, Miss Vendegast and Miss Huller have hypnotized two police officers, and are laughing at them while the latter are unable to react. Having removed one of the officers’ trousers and underwear, the three witches are seen playing with his naked body, placing a pen, a meat-hook, and a gun next to his genitals, as if ready to castrate him. The women’s deafening laugh, their use of long phallic props, as well as their derisive and aggressive preoccupation with the man’s genitals, reinforce stereotypical representations of the witch as a phallic woman whose main purpose is to cause ‘male impotence’ (Creed, 75). Furthermore, Helena Markos, as the embodiment of the film’s evil, is given the most stereotypical representation. The first time she is present in the film, we are only allowed to see her hand touching the ceiling, above which Susie is dancing. Her hand, wrinkled and full of blisters, together with her long, neglected nails, and the sound of her coarse breathing, convey a repulsive image of a living corpse. The shot showing Markos’ hand reaching up with her long fingers, juxtaposed against the shot of Susie dancing, as if the former is attempting to grab the latter, perpetuates the archetype of the monstrous archaic mother seen ‘as the abyss, the all-incorporating black hole’ (Creed, 27) which threatens to absorb life instead of generating it. The abjectness of Helena Markos is further highlighted in the climactic sequence of the film during the Mutterhaus ritual. In this sequence, the entirety of Markos’ body is visible, revealing a figure that looks less like a human body, and more like a decaying mass of flesh. During the sequence her speech is slow and overly-simplistic, as if underdeveloped, and often instead of expressing meaning through human speech, she produces sounds, shrieking, hissing and whimpering. Helena Markos’ underdeveloped speech, and reliance on physical meaningless sounds, further enhance her abjectness, signifying, as per Creed, ‘a collapse of the boundaries between human and animal’ (10).

In contrast to Suspiria (1977), Suspiria (2018) subverts the original narrative by revealing that Susie, previously a final-girl, is now Mother Suspiriorum, able to dethrone Helena Markos, and assert her dominance over the coven. Presented as a witch herself, Susie evidently demonstrates elements of the abject throughout the film. Her abjectness is vividly demonstrated in the sequence when she auditions for Olga’s part, while Olga is trapped in the academy’s basement. After Madam Blanc casts a spell on Susie, the latter becomes able to control Olga’s body, breaking her bones and tendons with every movement she makes. After the end of the dance Olga’s body is folded in two, as she is covered in blood, saliva and urine. Susie’s abject effect on Olga’s body might not be consciously induced, but it reveals her violent power and ability to cause lethal harm. Furthermore, in the climactic scene of the Mutterhaus ritual, Susie summons death and kills Markos and her supporters. During the scene Susie’s abjectness becomes evident, as her command ‘Death to any other mother’ causes Markos to vomit blood, before slowly dying, and Markos followers’ bodies to violently explode. While the scene’s violence is undeniable, it would be hard to read Susie’s action as a ‘destruction of the symbolic order’ (Creed, 76), as the impact of Markos throughout the film was associated with division within the academy. Thus, one could argue that through the extermination of Markos and her followers, Susie rather restores social order, and expels elements of deception and manipulation from the academy. Furthermore, the film’s climactic sequence reveals another trait of Susie, namely her ability to redeem, opposing the trope that the witch ‘is an inversion of the good woman’ (Young, 154). After killing Markos and her followers, Susie approaches Olga, Patricia, and Sara asking them one by one what they wish. The girls all wish death, and Susie kisses them with tenderness causing them to die peacefully, in contrast to Markos and her follower’s cruel death. In a later scene, Susie visits Klemperer and after revealing to him what truly happened to his wife, she erases his memory, as a way to relieve him from his guilt. Susie’s simultaneous ability to provoke violence and death, associating her with the abject, as well as restore balance and relieve pain, which could be read as a form of maternal healing, subvert the stereotypical tropes of witch representation, ultimately suggesting that ‘it is possible to have a relation to abjection while at the same time being a […] unifying force’ (Davies, 52).

Suspiria’s (2018) reliance on established tropes of witch representation for the characterization of figures such as Markos and the academy’s professors, who abuse their power for their amusement, associates them with the abject, while at the same time, marking them out as morally indictable. Furthermore, most of these figures die, ‘in order finally to eject the abject’ (Creed, 14) and restore the symbolic order. Interestingly however, this does not happen with Susie despite her abject nature. Not only is she not ejected as an immoral, abject element, but she is herself the character whose judgement determines who will be ejected. The film refrains to juxtapose the abject ‘Markocite’ —as used by Klemperer to describe Markos and her followers— figures against their polar opposite, namely an entirely virtuous witch figure. Instead, it allows for the exploration of a similarly abject figure, Susie, who is nonetheless able to restore balance, and occasionally behave as an ‘upholder of morality’ (Young, 154). The film’s ability to renounce the archetypal binary of ‘bad’ castrating witch, and ‘good’ nurturing witch, allows for a rare exploration of monstrous femininity as a multi-dimensional condition, able to define itself reflectively and dynamically.

Suspiria’s (2018) warning Alongside the inversion of Susie Bannion’s role in Guadagnino’s Suspiria (2018), another major difference of the remake is the socio-political timeframe in which Guadagnino and Kajganich choose to situate the world of the film. In contrast to Argento’s Suspiria (1977) which was situated in Freiburg, and was ‘devoid of historical, and maybe even cultural, specificity’ (Corcoran), Suspiria (2018) takes place in divided Berlin during the German Autumn of Terror in 1977. The film begins with a long shot of Patricia looking around bewildered and scared, while a crowd is heard chanting in the background, before a man shouts ‘Free Baader’. As Patricia starts walking and the camera follows her, a violent demonstration is revealed, with protestors demonstrating the arrest of Meinhoff and Baader, founding members of the far-left militant organization RAF (Red Army Faction), before an armed array of police-officers. Patricia, walks through the protest, looking evidently lost, and heads to Klemperer’s office. Upon her arrival, she starts exhibiting signs of mental instability: singing, obsessing over inanimate objects, and suffering abrupt changes in emotion. As Patricia reveals her theory that the academy is run by witches, the sounds of a bomb is heard from the room’s window, followed by the sound of people shouting. Some seconds later, a shot featuring Klemperer’s notebook reveals his conclusion that Patricia’s ‘delusion has deepened into panic’. In the next shot Klemperer is seen quickly closing the curtains of the room’s larger window, as if trying to reduce the presence of the outside world inside the room, ultimately drawing a parallel between Patricia’s mental turbulence, and the political upheaval of divided Berlin. Guadagnino’s choice to begin the film with a shot amidst a political clash, as well as present a mentally unstable character whose tumult appears to be associated with the violent political crisis, highlights the importance of the socio-political context in the film, and invites the audience to explore its significance in relation to the film’s characters.

Furthermore, the first time we see Susie in Berlin, on a gloomy rainy day, she is walking by the Berlin Wall. On the wall are written some faded phrases including the phrase ‘Freiheit fur alle’, which translates to ‘Freedom for all’, with the word ‘alle’ looking as if having been erased. Soon Susie finds the Tanz academy, which is situated right beside the Berlin Wall, and enters the building. The scene’s grey colours and heavy atmosphere, together with Guadagnino and Kajganich’s choice to situate the academy right beside the Berlin Wall -Berlin’s literal point of separation- highlights the film’s overarching theme of social division. As Susie walks further into the academy she notices a showcase with the pictures of the academy’s teachers. The showcase has two doors, making the pictures inside it appear as two separate columns. As Susie walks closer to the showcase, the camera pans upwards, revealing the top of the showcase, where the pictures of Helena Markos and Madam Blanc are placed, as if visually representing the academy’s opposing rivals, and thus its internal division. A sequence that further highlights the academy’s division is the voting sequence, when the teachers decide who will be the academy’s new leader. The sequence begins with Miss Vendegast humming peacefully, before she is interrupted by an abrupt voice initiating the elections. Without ever seeing the face of the person talking or the face of the people voting, each of the teachers are asked to name their preferred candidate, as the names Markos and Blanc are heard interchangeably. The fact that we never see the face of the teachers voting, which would allow us to associate particular individuals with their chosen belief systems, creates a diffused sentiment of suspicion, and social turmoil. When the voting ends, and Helena Markos is proclaimed as the academy’s leader, Miss Huller turns on the radio. As the scene progresses the broadcaster is heard discussing the October hijacking of a Lufthansa airliner by which the RAF demanded the release of imprisoned RAF members, threatening the Schmidt government that if the request was not met by ‘8:00 a.m. on Sunday, October 16, the hostages would die’ (Hanshew, 225). The invasion of the film’s socio-political context in this scene, highlights the prevalence of polarisation and division within German society during the autumn of 1977, as well as foreshadows the potential consequences of a corrupt leader’s abuse of power.

Guadagnino and Kajganich’s choice to situate their remake of Suspiria in a new context, and explore through it issues of polarisation and leadership crisis, as well as make references to Germany’s Nazi past, most notably through Klemperer’s character ‘who is still dealing with the trauma of losing contact with his wife during the Second World War’ (Davies, 51), could allude to the creator’s intention to produce a wider commentary on contemporary issues of political polarization and social division. It would be important to mention that the production of Suspiria took place during 2016, with the filming specifically commencing on December 2016, a month after the 2016 US presidential election, won by Donald Trump, a period which played a major role in the contextualization of the characters and their attitudes in Suspiria. In an interview with Eninias, Guadagnino discusses the importance of 2016, explaining that it was ‘the year whenthe actual unravelling of this very severe division in American society began to explode’ particularly referring to the ‘brutal awakening that was the Trump election’ (Guadagnino in Encinias). Further elaborating on Trump as a figure, Guadagnino did not hesitate to describe the former president as a ‘plutocrat and showman […] who narcissistically wants to be loved and adored’ (Guadagnino in Encinias). One could argue that Guadagnino’s views on Trump, are reflected in Suspiria (2018) through the figure of Helena Markos, her attachment to power, and her use of misinformation in order to remain the leader of the coven. Her followers’ naive loyalty to her constructed narrative that she is Mother Suspiriorum is most notably presented through Miss Tanner and Madam Blanc’s discourse during which the former refers to Markos as ‘Mother’. Instantly, Blanc corrects her, explaining that ‘If Markos really were one of the Three Mothers [they] wouldn’t be in this situation’. After a short altercation Miss Tanner concludes that Blanc is ‘not the light [they]chose to follow’ implying that despite the fact that Markos’ story is not sufficient enough to be credible, they have decided to follow her regardless, essentially suggesting a blind faith in her constructed narrative. Nonetheless, the film’s climactic sequence condemns Helena Markos. When Susie asks Markos ‘for whom [she was]anointed’, the latter hesitates to respond, and when she finally answers ‘Mother Suspiriorum’, evidently lying, she is met with death. Suspiria’s (2018) occupation with issues of political turmoil and social division, could be seen as reflecting the polarization of the US society amidst the 2016 presidential election, and could simultaneously function as a ‘plea for engagement with the emerging threat of right-wing ideology’ (Davies, 52) across Europe and America.

References

Corconan, Miranda. “Suspiria (2018): Six Responses and an Epilogue.” amiddleagedwitch.wordpress.com.18 Mar. 2019. Web. 10 Jan. 2022.

Creed, Barbara. The Monstrous-Feminine, Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. Oxford: Routledge, 1993. Print.

Davies, Luke. “Appropriating the Abject: Witchcraft in Dario Argento and Daria Nicolodi’s Suspiria (1977) and David Kajganich and Luca Guadagnino’s 2018 Remake.” New Cinemas, 18 (2020): 43-59. Print.

Encinias, Joshua. “Luca Guadagnino Talks We Are Who We Are, Loving Your Actors, and the Suspiria Sequel That Won’t Happen.” thefilmstage.com. 12 Nov. 2020. Web. 10 Jan. 2022.

Francis, James. Remaking Horror: Hollywood’s New Reliance on Scares of Old. North Carolina: McFarland Books, 2013. Print.

Hanshew, Karrin. Terror and Democracy in West Germany.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. Print.

Jagernauth, Kevin. “David Gordon Green Says ‘Suspiria’ Would’ve Been “Operatic,” Remake Still Happening But He Won’t Direct” indiewire.com. 24 Jun. 2015. Web. 10 Jan. 2022.

Kilday, Gregg. “Amazon vs. Netflix: An Epic Oscar Battle Begins“ hollywoodreporter.com. 2 Nov. 2016. Web. 10 Jan. 2022.

Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror, An Essay on Abjection. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982. Print.

Lang, Brent. “‘Suspiria’ Dares CinemaCon Crowd Not to Vomit With Gruesome Footage” variety.com. 26 Apr. 2018. Web. 10 Jan. 2022.

Maddaus, Gene. “Amazon Sued Over Use of Artist’s Work in ‘Suspiria’” variety.com. 27 Sep. 2018. Web. 10 Jan. 2022.

Mumford, Gwilym. “Luca Guadagnino on Call Me By Your Name: ‘It’s a step inside my teenage dreams’” theguardian.com. 22 Dec. 2017. Web. 10 Jan. 2022.

Now Screaming on Prime. “This is accurate” twitter.com 18 Jun. 2018. Web.10 Jan. 2022.

Strowbridge, C. “Theater Averages: Suspiria Surprises with Yearly Best Average” the-numbers.com. 31 Oct. 2018. Web. 10 Jan. 2022.

Verevis, Constantine. Film Remakes. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006. Print.

Weintraub, Steven. “Amazon just world premiered a scene from Luca Guadagnino’s ‘Suspiria’ remake and it’s one of the most fucked up things I’ve ever seen at #CinemaCon. People at my table turned away from the screen. All I can say is it’s beyond extreme and gross and I need to see more.” twitter.com. 26 Apr. 2018. Web. 10 Jan. 2022.

Young, Serinity. Women Who Fly: Goddesses, Witches, Mystics, and other Airborne Females. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018. Print.

Written by Maria Nephele Navrozidi (2022); Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright ©2022 Maria Nephele Navrozidi/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post