Plot New York. 1987. Patrick Bateman, a 27 year-old Wall Street stockbroker spends most of his considerable income on clothes, dining out and clubbing. He circulates amongst a group of work colleagues who frequently mis-identify one another. Bateman is notionally engaged to Evelyn Williams and conducts an affair with her best friend Courtney Rawlinson. Courtney, in turn, is addicted to tranquillising drugs and engaged to Bateman’s friend Luis Carruthers. Bateman is undermined by the presence of Paul Allen, a Wall Street rival. In a rage Bateman kills, first, a street bum, then Allen. A private investigator, Donald Kimball, turns up at Bateman’s office enquiring into Allen’s disappearance. In an excessive sex romp Bateman mutilates, but does not kill, two prostitutes. Later, he has a dinner date with his secretary Jean, who is in love with him, but (following a telephone call from Evelyn) asks her to leave before he hurts her. Revisiting one of the prostitutes from his earlier encounter, he instigates another threesome in which he kills both women. He shoots an old woman who intervenes when he taunts a cat, and this leads to a police chase. Killing the cops, and a security guard, he takes refuge in his office where he phones his lawyer, Harold Carnes and confesses everything to Carnes’ answering machine. When he next visits Allen’s apartment (where he has hidden bodies), he finds it up for sale and being redecorated. At a bar he encounters Carnes who first mistakes him for someone else, then dismisses his confession as a joke. As Bateman becomes more insistent, Carnes gets annoyed and tells him that his confession is impossible for he (Carnes) has just got back from London where he had lunch with Allen on two occasions.

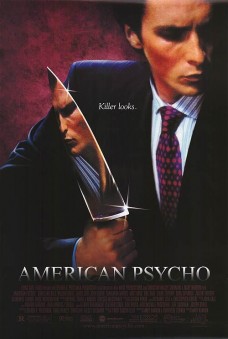

Film note American Psycho marks the end of a decade-long cycle of serial-killer movies that began with the phenomenal success of The Silence Of The Lambs (1991). The notoriety of the source novel by Bret Easton Ellis, a string of well-documented pre-production problems, and a range of conflicting responses to the film make it a useful indicator of trends within the film industry and within American society.

Lions Gate and Generation X Bret Easton Ellis’s source novel has been described as “one of the key works of our age” (Grant 25). It also encapsulates an era, being “a classic of the 1980s. In a sense it is the 1980s” (Young 88). The novel’s success notwithstanding, adapting American Psycho was always going to be a tricky prospect. David Cronenberg, for example, expressed an early interest–“I was amazed at how good the book was. I felt it was an existentialist epic”–but concluded that it was unfilmable (qtd. in Kaufmann 249). A nervous Simon & Schuster dropped the book on the instructions of its parent company, Paramount, which may well have been put off by the controversial subject matter but perhaps also objected to the novel’s scathing critique of the very films, TV shows and CDs being produced by the new media conglomerates (including Paramount) that had grown up as a result of Reagan’s laissez-faire economics.

That the book was eventually optioned, filmed and distributed has much to do with the way Hollywood in the 1990s annexed the zeitgeisty worldview found in Ellis’s novels, a worldview encapsulated in Douglas Coupland’s iconic novel Generation X (1991). The relative success of films such as Slacker (1991), Dazed And Confused (1993), Clerks (1994), Kids (1995) and The Doom Generation (1995), and adaptations of the novels Bright Lights, Big City (1998), Slaves Of New York (1989) and Ellis’s own Less Than Zero (1987), paved the way for the green-lighting of American Psycho, a kindred, though altogether darker piece of work.

The film was financed by Lions Gate Films, which describes itself as an “integrated global entertainment company” aiming to produce “original, cutting edge, quality entertainment in markets world-wide” (“Lions Gate”). Lions Gate is vertically integrated with interests in exhibition, distribution and production, and divisions that encompass motion pictures (including home video), television, animation and digital media. It has a studio in Canada, offices in New York and a 45% equity investment in Mandalay Pictures, which produces more mainstream fare. Lions Gate is modelled on Miramax but with a larger portfolio. Where Miramax promoted Larry Clark’s controversial debut feature kids, Lions Gate have now acquired his equally controversial third feature Bully (2001). In Justin Wyatt’s account of Miramax’s formation as a “major independent” he states that Miramax frequently “maximized the publicity created by challenging the MPAA ratings system” (Wyatt 80). Lions Gate had a similar battle with the MPAA over a scene in American Psycho, in which Bateman has sex with two prostitutes. Eventually agreeing to the cuts, Lions Gate nonetheless invested $100,000 in an official website (now an established movie marketing strategy) which promised those who registered, “emails from Patrick Bateman” containing video of the excised scenes.

But, as John Pierson notes, “the definition ‘independent’ is much more elusive now than a decade ago” (qtd. in Hillier xvi). Lions Gate’s opportunist approach makes this clear: at one point in the film’s troubled pre-production history director Mary Harron was sacked as Lions Gate attempted to entice Leonardo DiCaprio to play Bateman (Harron was fervently against his casting). The temptation of adding to the project the commercial security of an A-list star fresh from leading roles in box office hits Romeo And Juliet (1996) and Titanic (1997) was too much, even for a company with a commitment to “cutting-edge young talent”. DiCaprio eventually turned down the offered $21m salary and Harron was brought back on board to make the movie for a total of $7m.

Much has been was made of Harron’s gender and the perspective this gives her on such potentially volatile material. When Ellis was not being revered as a cultural genius he was being attacked as a vicious pornographer and misogynist and as Reese Witherspoon stated in an on set interview: “[American Psycho] needed a female director” (“Lions Gate”). It would be simplistic to state that a female presence behind the camera would automatically prevent anti-feminist charges from being levelled at the film. Harron’s background as a documentary film-maker for the BBC, and her introduction to feature film-making by the “Queen Of Queer” Christine Vachon, one of the 1990s most successful independent producers (responsible for nurturing Todd Haynes and Todd Solondz), guaranteed the production some protection from feminist critics. Harron employed lesbian icon (and star of the lesbian sleeper hit Go Fish (1994)) Guinevere Turner to both co-script and star. There is little of Harron’s documentary background in evidence in American Psycho, but there is evidence of her work on challenging television dramas like Homicide: Life on the Street (1993-99) and Oz (1999-2003). This crossing of boundaries–from straight to queer, from fact to fiction–may well be part of the reason why American Psycho has been so variously understood and why the film manages to shock its viewers and unsettle interpretation.

It may have been the logistics of semi-independent studio economics that prevented the production from location shooting around any of New York’s famous landmarks, but the aesthetic effect of the film’s more anonymous look is that it can represent any cosmopolitan urban space. As recent events in the UK–Fred and Rose West, Dr Harold Shipman–have shown, the phenomenon of serial killing is a transnational phenomenon, as is a general fascination with the means and motives of such killers. In the global environment in which Hollywood operates this ability to move across and beyond distinct national markets is commercially vital.

Serial killer as symptom American Psycho, and the serial killer genre more widely, have been viewed as allegorical works that “act out the enraged confusion with which Americans have come to regard their post-war economic and social experience” (Newitz 66). Symptoms of this “enraged confusion”, or what has rather vaguely been described as “millennial angst”, include: renewed interest in investigative TV cop shows marking an unhealthy interest in gruesome murder (NYPD Blue (1993-ongoing), Homicide: Life On The Street; acts of random and apparently unmotivated extreme violence (the Uni-Bomber, the Columbine killings); loss of faith in established forms of authority (politics, religion, work, the law); a revival of religious cults (as in Waco, Texas); a period of anti-intellectual “feminism” and a conversant hardening of masculinity (Sex In The City (1998-ongoing), Men’s Lifestyle magazines, “Girl Power”), the body as a site of narcissistic self-regard and commodification (new-age therapies, diet and exercise regimes, the “six-pack phenomena”); the success of “car crash” confessional/reality TV (The Jerry Springer Show (1991-ongoing), Big Brother (2000-ongoing); and the saturation of the public sphere with marketing images in the service of a rampant consumerism. Patrick Bateman is symptomatic of this “enraged confusion”; his individual pathology presented as that of a nation in crisis.

If it is possible to diagnose US culture as displaying a “collective and national psychopathology,” the diagnosis offered by American Pyscho would seem to be one of (near terminal) narcissism (Seltzer 101). The psychologising of experience and the vicarious consumption of this psychologising are both marked features of US popular culture. Mark Seltzer notes, for instance, that, “there appears an insatiable public demand – in print media, drama, films, and television – for accessible, entertaining information on psychological disturbances and psychiatric experts” (101). Seltzer argues that this “reflects both the ‘culture of narcissism’ and the ‘narcissism of culture’” (101). By allowing its protagonist, Patrick Bateman, to endlessly reflect upon his place in society (“I just want to fit in”), and upon his image in mirrors (Nick James called the film “a fetishised hall of mirrors for mirror men” (23)), American Psycho makes narcissism a central theme. Formally speaking, the film–through its parody and aesthetic mimicking of the advert, the TV cop show, the slasher movie and the lifestyle magazine feature–also comments self-reflexively on the “narcissism of culture”.

The title sequence of American Psycho demonstrates this well. The movie opens with a visual joke on blood and nouvelle cuisine, and then moves to a nightclub where Bateman reveals his psychotic imaginings. Later, the camera tracks majestically through a “perfect” Upper West Side apartment, with John Cales’ non-diegetic, elegiac music emphasising the movement of the camera. We catch glimpses of Bateman in long shot as he passes through the space, then watch as he administers his obsessive daily ablutions and conducts the ritual of his exercise regime. The sequence is a cinematic re-enactment of a life-style magazine feature article in which everything is a commodity; from haute cuisine food to the perfect body, each item presented as desirable and attainable. Within this realm the individual is shown to be dissolute and isolated, formed from the very things that surround them. As Bateman peels off his herb-mint facial-mask he introduces himself in voiceover as an “abstract”, a gestalt of the time and place he inhabits.

American Psycho depicts a “culture of narcissism” at large in the 1980s (the time in which the novel was written) and still at the heart of US society in the 1990s and 2000s. The film is distinctive in this regard, avoiding other diagnoses such as “Prozac nation” and “trauma culture” that have been used for the contemporary period (Seltzer 101-104). It offers little by way of relief from this perspective, even narrativizing the concept that this narcissism is a common characteristic of all who inhabit the world depicted, as Bateman is confused in the final scene for other Wall Street brokers, some of whom he may or may not have killed. The consistent sameness of the form of self-identification depicted (that is, the purchase and clever deployment of consumer products and pop culture trivia) leads to identity slippage among an entire social group. The comparable clothing, acting mannerisms and hairstyles of the actors playing brokers in the film asserts this similarity throughout.

Violence begets violence A key issue that has split reviewers is whether the film glorifies or critiques screen violence. In the 1996 presidential election campaign both Bob Dole and Bill Clinton made impassioned remarks about the perceived immorality of violence within the media. In 1999, when two young men in Littleton, Colorado entered their high school and shot dead fifteen of their fellow pupils, a US Senate Committee hearing was convened to hear testimony from media experts about the possibility that screen violence had been a contributory factor. The results of the hearing were inconclusive but American Psycho seems willing to suggest that the representation of violence does beget actual violence (Slocum 23). In the novel Bateman watches Brian De Palma’s Body Double (1984) thirty-six times. In the movie he is seen watching The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), which he then mimics in one of his bloody murders. Here the film’s mise-en-scene clearly makes the connection between violence and the consumption of violent cultural material. Furthermore, the film also suggests that all forms of consumption breed a narcissism and alienation, the end point of which is psychopathy and murder. Alongside films like Memento (2000), The Usual Suspects (1995), Fight Club (1999) and Mulholland Drive (2001), American Psycho investigates the complex tensions between fantasy and fact – the lack of any clear distinction between living our lives “like the movies” and living our lives within the reality of domestic violence, poverty and banal ”McJobs”.

However, a conceit of the novel occasionally overshadowed by the brutal slayings and unwavering references to luxury brands is the unreliability of Bateman as narrator of his life and crimes. Tony Rayns suggests that the film “presents its psychotic episodes as fantasies from the get-go”, but such a claim indicates a stylistic shift between these sequences and those on Wall Street which is not present” (Rayns 42). American Psycho operates at a high level of absurdity throughout (a brief hand-holding at traffic lights perhaps notwithstanding) and in doing so stresses the superficiality of both 1980s existence and the perception of it by Bateman himself. Nicole Rafter has noted “a new type of crime film that, because it goes so far in the burlesque of traditions, might best be labelled absurdist… Recent absurdist films share [a] taste for fantastical, semi-comical violence… They reach out to a younger audience more tolerant of screen violence and its comedic potential and more likely to have been bred on the rapid-fire editing of MTV and on commercials’ disjunctive style” (40). Rafter cites serial killer movie Natural Born Killers (1994) as one example; American Psycho is certainly another. The conclusion of the film offers the clearest example of this tendency: if the murders are just a figment of Bateman’s fevered imagination then he is no more a danger to society than those who relentlessly consume violent movies. When Bateman states in voiceover “there is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction. But there is no real me; only an entity, something illusory” he is speaking the truth, for he is a construction, a character in fiction. Further blurring this line, the script has Bateman, when he phones his lawyer, confess to crimes perpetrated within the novel but not shown by the film, as though he himself has read Ellis’s work and become psychotically unhinged by it, unable to tell reality from fantasy–precisely the dangerous consequence those who would ban the book warn against.

On the face of it American Psycho’s very title would suggest that this is a quintessentially American film. It depicts a moment in the Reagan administration (even featuring that President on a television in the background of the final scene) but is responsive to its own time as well. Sight and Sound’s cover feature was blazoned with the caption “American Retro” but the film also comments on Clinton’s presidency–in its final year when the film was released–which was marked not just by domestic policies of social inclusion but by the lack of a clearly defined foreign enemy, which re-focused attention towards domestic concerns. His inaugural address in 1993 called for a “season of renewal […] to define what it means to be an American” (Campbell and Keen 28). But in his second term Clinton’s own domestic scandals–along with “media events” like the OJ Simpson trial, Waco, the Columbine high-school shootings and the brutal murder of gay teenager Matthew Shephard–revealed an America far from “renewed”. The Oklahoma City bomb, initially blamed on Islamic terrorists, was found to be the work of a disenchanted American, a sudden act of violence from within. The serial killer movie is perhaps the flipside of the disaster genre: whereas disaster enacts fears of apocalypse in the public, global domain, serial killer movies enact the fear of apocalypse in the private, domestic space, in the mind of the individual. What makes American Psycho so difficult is its positioning of the killer not as a drifter or a loner, but as a man who “needs no introduction” (as one of the movie’s taglines put it), because he is our neighbour, or brother-in-law, or sitting next to us on the subway.

References

Campbell, Noel and Alasdair Keen. American Cultural Studies: An Introduction to American Culture. Routledge: London, 1997. Print.

Coupland, Douglas. Generation X. New York: St Martin’s Press, 1991. Print.

Ellis, Bret Easton. American Psycho. London: Picador, 1991. Print.

Grant, Barry Keith. “American Psycho/sis: The Pure Products of America Go Crazy.” Mythologies Of Violence in Postmodern Media. ed. Christopher Sharrett. Detriot: Wayne State University Press, 1999. Print.

Hillier, Jim, American Independent Cinema. London: BFI Publishing, 2001. Print.

James, Nick, “Sick City Boy.” Sight And Sound, 10.5 (2000): 22-24. Print.

Kauffman, Linda. Bad Girls And Sick Boys. California: University Of California Press, 1998. Print.

“Lions Gate”. Lionsgatefilms.com. Web. 19 Mar. 2002.

Newitz, Annalee. “Serial Killers, True Crime and Economic Performance Anxiety.” Mythologies Of Violence in Postmodern Media. ed. Christopher Sharrett. Detriot: Wayne State University Press, 1999. Print.

Rafter, Nicole. Shots In The Mirror: Crime Films And Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. Print.

Rayns, Tony. “Review: American Psycho.” Sight And Sound, 10.5 (2000): 42. Print.

Seltzer, Mark. “The Serial Killer As A Type Of Person.” The Horror Reader. ed. Ken Gelder. London: Routledge, 2000. Print.

Slocum, J. David. “Violence and American Cinema: Notes For An Investigation.’ Violence And American Cinema. ed. David. J. Slocum. London: Routledge, 2001. Print.

Vachon, Christine. Shooting To Kill. London: Bloomsbury, 1998. Print.

Vincendeau, Ginette. Film/Literature/Heritage. London: BFI Publishing, 2001. Print.

Wyatt, Justin. “The Formation of the ‘Major Independent’: Miramax, New Line and the New Hollywood.” Contemporary Hollywood Cinema. ed. Steve Neale and Murray Smith. London: Routledge, 2000. Print.

Young, Elizabeth “The Beast in the Jungle, The Figure in the Carpet.” Shopping In Space. ed. Graham Caveney. London: Serpents Tail, 1992. Print.

Written by Andrew Copestake (2003), London Metropolitan University; edited by Guy Westwell (2011), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2011 Andrew Copestake/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post