Plot Los Angeles, present day. Tom, a greeting-card copywriter and incurable romantic, has been dumped by the beautiful Summer, his ideal girl. He sifts through their 500 days together looking for what went wrong. The movie flashes back to their workplace courtship and his growing infatuation. A karaoke evening brings them together and they start dating “casually” at Summer’s suggestion. She refuses to believe in love. Tom is entranced by her wacky bohemianism in their blissful early days together. She encourages him to go back to architecture, the career he abandoned. Tom’s romantic streak and Summer’s insistence on a “no label” relationship puts them under stress. They break up, are reconciled, but finally she leaves him and the company. Some months later at a workmate’s out-of-town wedding, they share a romantic interlude. Summer invites him to a party, where his romantic expectations come up against the problematic reality: Summer has become engaged to someone else. Crushed, Tom denounces the cruel mythmaking of greetings cards, quits his job and seeks work as a trainee architect. Later he meets Summer by chance, and she confesses to him that now she believes in fate, after finding her husband. At a job interview, Tom falls for Autumn, a cute fellow-applicant (adapted from Stables 64).

Film Note (500) Days of Summer (2009), the directorial debut of Marc Webb, can be located amongst an array of semi-independent films that have been released in recent years by Fox Searchlight Pictures, most notably Napoleon Dynamite (2004), Little Miss Sunshine (2006) and Juno (2007). Such films illustrate the changing production trends within contemporary US cinema, whereby the boundaries between major studio and independent filmmaking are beginning to blur. Between the Hollywood blockbuster and the low–budget indie feature there now lies a zone some critics have labelled “Indiewood”, an “area in which Hollywood and the independent sector merge and overlap” (King 1). Hollywood’s reliance on “semi-independent” filmmaking can be traced back to the 1980s, when major studios began to set up or acquire smaller production divisions to produce specialist or obscure films on a low budget. These included studio-created subsidiaries such as Sony Pictures Classics and Fox Searchlight Pictures as well as “formerly independent operations taken over by the studios,” a prime example of which was Disney’s acquisition of Miramax in 1993 (King 4).

Two events paved the way for the major studios’ move into the independent sector: first, sex, lies and videotape (1989) won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival; second, Pulp Fiction (1994) received phenomenal commercial and critical success, leading Xan Brooks to suggest that Quentin Tarantino’s film “repositioned the goalposts of American cinema, blurring the boundary between mainstream Hollywood product and the independent fringe” (11). Pulp Fiction–estimated budget $8m, total domestic gross over $100m–can therefore be viewed as being “part of a wider story of the dismantling, or transformation, of the structures of independent production and distribution which characterised the 1980s”, leading to the search for suitable hybrid terms–“off-Hollywood”, the “major-independent”, “Indiewood”–to describe the new economic reality (Hillier 255).

The rise of the semi-independent film is evident in the sheer volume of independent/semi-independent films being screened at the Sundance Film Festival, with numbers exceeding 5,000 in 2007 compared with only 500 in the previous decade. As John Patterson notes, “mainstream Hollywood has […] not simply co-opted indiedom, but also been taken over by its sensibility” (2). In this light, the term “independent” can be viewed as being “more of a marketing label than a definition rooted in a film’s conditions of production and distribution” (Hillier 258). That is not to say that the quality or independent spirit of films within the Indiewood sector is attenuated, as these subsidiary studios “are usually given a significant degree of autonomy from their corporate parents, often including the power to green-light production or make acquisitions up to a particular financial ceiling” (King 6). This is the case with Fox Searchlight Pictures, founded in 1994 as the independent arm of parent company 20th Century Fox, and home to (500) Days of Summer. Company president, Peter Rice explains that “[Fox Searchlight] is integrated with the mothership” and as a result receives “all the benefits of a big corporate parent” (most notably international distribution) but that the company is also “able to do things in different ways from the main studio”. The deal pivots on one core mandate: every movie that Fox Searchlight produces must be profitable before entering the home video market, something that was achieved with (500) Days of Summer (Thompson).

The film’s script, written by Scott Neustadter and Michael H. Weber, had a rather typical Hollywood backstory–it was rejected by all the major studios before finally being optioned by Fox Searchlight after music video director Marc Webb spent three months working up countless storyboards and concept art. The film was then made for an estimated production budget of $7.5m (some of which, it is claimed, came out of Webb’s own pocket). A standing ovation at the film’s January 2009 premiere at the Sundance Film Festival (a reception comparable to that of Little Miss Sunshine at Sundance or Juno at the Toronto Film Festival), suggested that the film was going to do well.

The marketing team modelled their strategy on that of Juno (another Fox Searchlight film) which opened on only seven screens in December 2007 with a box office take of just $500,000 and then, after picking up rave reviews, was given a large-scale release, quickly becoming the first Fox Searchlight picture to surpass $100m. Positioned for release from July 19, a date set to mirror the seasonal title, (500) Days of Summer had a similar “platform release” on only twenty seven screens, with an increase to 1048 by August 7. At the end of its theatrical run, the film had made over $60m worldwide, clearing nearly five times its budget domestically. In proportion to its budget, (500) Days of Summer was more profitable than both the 2009 installments of the Harry Potter and Transformers franchises, demonstrating an exceptional return on investment.

Akin to the style of both Juno and Little Miss Sunshine (two of Fox Searchlight’s biggest success stories), (500) Days of Summer combines an alternative soundtrack (Regina Spektor and Belle & Sebastian), a somewhat unusual cast (Joseph Gordon-Levitt had until this point been cast in dark emotional dramas such as Mysterious Skin (2004) and Brick (2005)) and an offbeat aesthetic style, including the use of animation and pencil shading. As the box office figures suggest, this mixing of arty and kooky elements with a broader commercial appeal ensured that the film played well in niche as well as mass markets, allowing Fox Searchlight, and especially its parent corporation, to “share in the windfalls that accrue to occasional large scale independent hits” (King 6). The Indiewood approach has further advantages for the major studios. It provides a way of bringing “new filmmaking talent into their orbit” who might then go on “to serve mainstream duty”: Marc Webb for instance has been chosen to direct the upcoming Spiderman reboot, while a successful film such as (500) Days of Summer can also launch an actor’s career, as proved by Gordon-Levitt’s subsequent roles in blockbusters such as G.I Joe: The Rise of Cobra (2009) and Inception (2010) (King 6).

Too-cool-for-school As previously mentioned, (500) Days of Summer has much in common not only with Juno (both films share producer Mason Novick and director of photography Eric Steelberg), but also with Sony Pictures’ Nick & Norah’s Infinite Playlist (2008); the clear affinity between these films is the dominant use of pop-culture and mass-media references, displayed through both product placement and more importantly intertextuality. The film is laden with allusions to film, music, art and consumer culture in general, including references to The Seventh Seal (1957), The Graduate (1967), Star Wars (1977), Knight Rider (1982-6), The Smiths, Magritte, Goethe, Nintendo and IKEA, to name but a few. Clearly, (500) Days of Summer has tapped into a tendency of the contemporary cinema to recycle and reuse culture to heighten or exemplify the core themes of the narrative (the use of IKEA in Fight Club (1999) and Wanted (2008) work in similar ways, for example). This tendency, whether explored through the film’s soundtrack, or through more overt cases of intertextual referencing (e.g. scenes copied from Fellini or the French New Wave), marks (500) Days of Summer as an exemplar of postmodern filmmaking. Perhaps aware of the fine balancing act between gathering in knowing fans who like this kind of “play” and alienating those who are unaware of the references, the film’s intertextuality is not a feature of the promotional trailer.

This reusing of culture within film remains at the heart of debates within the field of postmodern theory. As Robert Stam declares, “we dwell in the realm of the already said, the already read, the already seen” (304). Following Fredric Jameson, Stam goes on to note that that “most typical aesthetic expression of postmodernism is not parody but pastiche, a blank, neutral practice of mimicry” (305). Reviewing for Sight & Sound, Kate Stables picks up on both the pleasures and perils of postmodern aesthetics, praising the film as being “fascinating to the cinephile”, for it is “obviously a fond Generation-Y retread of Annie Hall (1977)” before stating that these “too-cool-for-school” references are “getting stale fast” (64).

Boggs and Pollard argue that many of the intertextual references in the film are “largely detached from [any sort] of historical context and meaning”, or, as in the case of the Nintendo and IKEA placements, function merely as a way for Fox Searchlight to gain funds to put the film into production (172-4). On first viewing, the scene in which Tom and Summer go to IKEA on day (34) of their (500) days together does seem to function in this way but rather than being an instance of empty “brand placement” this sequence does in fact amplify the film’s central themes–the fragility of love, the passing of time, the faultiness of memory–whilst also situating the action at the heart of consumer society.

The scene begins with a medium shot of Tom and Summer wandering through IKEA searching for trivets, Tom meanwhile mocking the Swedish store by asking Summer if she fancies buying a “Flug”. The depth of field not only allows us to see the vast amount of shoppers scrambling for their next buy, but also to the right of the frame the IKEA logo dominates our attention, the use of brand placement evidently being showcased for the audience to see. The pair then move into the home furnishing section, Tom sitting down on the sofa soon to be joined by Summer who asks, “Our place really is lovely isn’t it?”. She then begins to stare at the blank TV, presented through a shot/reverse shot, and pretends to be thrilled that American Idol is on. This is clearly a parody of the nuclear family, and this point is emphasised further when we see Tom sitting on an IKEA dining table pretending to eat a dinner that Summer, doing her best Donna Reed impression, has prepared for him. The couple then race to the bedroom, running through the IKEA store as if it was their own home. The sequence is intended to trigger pathos, as we know this is a future Tom and Summer will never share, and although this remains one of the happiest scenes within their relationship and a favourite amongst fans, the viewer can’t help but feel a sense of dread that their romance–especially when founded on such a saccharine image of domesticity–is fated to end. The careful use of mise-en-scène also makes an ironic reading possible: in the same vein that products from IKEA are relatively cheap and to a degree temporary, Tom and Summer’s relationship is equally fragile and transient; IKEA in this case could be seen as being a metaphor for their disposable love (as, more overtly, could Tom’s employment as a writer of greeting cards).

Once the couple reach the bedroom, aside from being interrupted by a Chinese family staring at them lying on the bed (another example of the globalisation in our current age), Summer tells Tom that she “isn’t looking for anything serious”. The scene ends with a slow tracking shot displaying the couple leaving the store with the camera lingering on the IKEA logo and the slogan: “We don’t make fancy quality, we make TRUE everyday quality”. As well as being superb advertising for IKEA, with the eighteen to forty-year old target demographic of the film perfectly matching that of the stores’ customers, the slogan may also refer to how relationships like Tom and Summer’s are part of the everyday, that like the vast reach of IKEA’s global empire, the film’s themes of love and heartbreak are universal. Thus, although the placement of IKEA is likely driven by commercial and opportunist motives on the part of Fox Searchlight, the film takes this brand placement and turns it into something that has depth and meaning, far from the blank “mimicry” theorists of postmodern cinema, like Stam, and Boggs and Pollard, have claimed.

The film’s co-writer Weber notes, “we were constantly exploring how people’s emotions and relationships are tied up in the culture all around us–in the songs, movies, books, television and art by which we define our identities” (Neustadter & Weber 114). This culture that moulds Tom, from The Smiths song “there is a light that never goes out”–which acts as the catalyst for his love for Summer–to his misunderstanding of The Graduate, was entirely present in the very first draft of the script. So whilst (500) Days of Summer is part of a trend in contemporary cinema, one which is typically informed by a postmodern culture of recycling and reusing, the references are not merely an afterthought but a central part of the film’s appeal. As film critic Roger Ebert puts it: “director Marc Webb seems to be casting about for templates from other movies [and songs] to help him tell this story; that’s not desperation, but playfulness”.

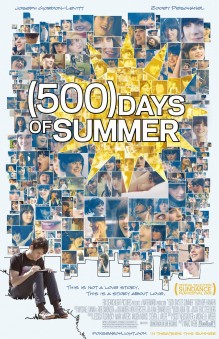

This is not a love story For all its intertextuality and postmodern play with film form, (500) Days of Summer displays an earnest desire to challenge the codes and conventions of the romantic comedy genre in order to tell a more truthful story about romance (Wiseman 11). As the tagline on the film’s poster states: “This is not a love story. This is a story about love.” This commitment to deconstructing the romantic comedy genre did not go unobserved, with The Guardian reviewer Eva Wiseman suggesting that the film sets out to instruct us that “everything we’ve learnt from Sandra Bullock and Kate Hudson, from the last 15 minutes of every ‘girls’ night in’, is all wrong” (Wiseman 11). Such words chime with Tom’s own diagnosis that the greeting cards he writes, the films he sees and the pop songs he listens to “are to blame for all the heartache”.

Two key elements mark out (500) Days of Summer from the wider genre. First, the film’s disjointed and unusual narrative structure (Ian Freer calls the film “a warm ‘n’ fuzzy Memento” (64)). Like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), which also tells a story of doomed romantic love through a non-linear narrative, (500) Days of Summer foregrounds the faulty processes of memory: depending on his mood, Tom can cite the exact same features of Summer’s character as attributes he finds affecting and that make him hate her, something the non-linear construction of the film highlights. This clever play with narrative structure serves as a “key marker of distinction” from mainstream romantic comedies (King 71).

Second, the film’s use of a masculine point of view places it in marked contrast to the other romantic comedies that came out in 2009, such as The Ugly Truth, The Proposal and She’s Just Not That Into You (Freer 62). Whereas the “post classical romantic comedy is usually associated with women, female concerns, female stars and female audiences”, (500) Days of Summer exploits the recent “re-gendering of the genre’s narrative” towards male experience, and even relies upon highlighting the presence of this subjectivity for much of its dramatic impact (Jeffers McDonald 146, 148). This is not a neutral exploration of romance; it is the (500) days as Tom remembers them, or rather how he wants to remember them. Michael Ordona, writing for the LA Times, comments on how the script’s “larger gestures, such as split screens juxtaposing reality and fantasy, as well as animated sequences, express Tom’s subjective view without mashing wrong notes”. This predominant change in gender roles places the film alongside recent texts such as I Love You, Man (2009) and Knocked Up (2007), and locates Hollywood’s move into the production of more masculine orientated “rom-coms”, or as Jeffers McDonald calls them, “homme-coms” (146). This masculine shift in the romantic comedy genre can be traced back to Swingers (1996), a film which “explores and tests the contours of the genre by repositioning the centre, rehearsing all the generic basics […] but mak[es] them new by considering them from a male point of view” (Jeffers McDonald 147).

This use of Tom’s point of view does have its limitations–as Kate Stables points out, “Summer in particular, viewed through the rosy prism of Tom’s obsession, is sometimes reduced to a cute, kooky enigma”–yet, this is in part extenuated through the careful thought given to the way the viewer is placed (64). As director Marc Webb explains, “Summer isn’t just a girl. She’s an event we have all experienced, and the attendant point of view shots that the film employs not only makes Tom’s depiction of her more real, but moreover, relatable” (Neustadter & Weber vii). A scene that perfectly captures Tom’s subjective and masculine point of view is the impromptu dance number to the Hall and Oates song “You Make My Dreams Come True” that follows his first night of passion with Summer. After coming out of his apartment block, the camera zooms in to an enormous grin on Tom’s face. As he struts down the street, we are shown Tom’s point of view as people nod, wave and clap at his success. Tom then stops to look at his reflection in a car window, only to see Harrison Ford as Han Solo wink back at him. We then cut to a long shot of Tom walking in the park, the fountains gushing as he walks past. A dance sequence then takes place, with Tom accompanied by marching band, animated bird and members of the public dressed in blue, a staple of the film’s colour palette used to match the colour of Summer’s eyes. An exposition of Tom’s inner euphoria, this scene indicates the extent to which the film is concerned with showing ostensibly accurate memories as simplified and over-inflated constructions of distilled emotion. By bordering on parody, this scene knowingly places Tom’s reverie into the universal sphere of masculine cliché whereby we as an audience relate to Tom’s happiness in a humorous manner, enforcing a reading centred on Tom’s success rather than his sex. The scene therefore functions in a similar manner to the scene in which Tom’s expectations and the reality of his situation are juxtaposed, only–coming earlier in the film than the later split-screen party arrival scene–this musical sequence is more open in its revelry and less tempered by the mundane.

As a “homme-com”, (500) Days of Summer does not simply attempt to depict a romance from a male point of view. During their break-up, Summer compares her and Tom to Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen. Yet Summer states that is she who is Sid, who stabbed Nancy to death. This reversal (Tom: “I’m Nancy?”) indicates the gender-slippage in wider contemporary culture and suggests the film is more interested in emotional realism than gendered pleasures (a claim backed up by the absence of overt sexualisation and eroticism). In this way the film moves away from the wider feminised genre of the romantic comedy and into a more realistic (the affair does not end well) and largely postmodern portrayal of love (tongue-in-cheek, knowing, philosophical). In the same way that typically postmodern cinema “gives rise to a popular mood of anxiety, fear, and pessimism”, (500) Days of Summer questions these anxieties by asking what truly happens when you fall in love, and more importantly how, as individuals, we react when the person we love breaks our heart (Boggs & Pollard 161). The answers inevitably involve the generic conventions of romantic comedy, just as the film shows needs and desires as inevitably influenced by popular culture and consumerism, but these conventions are revealed to be just as emotionally valid as they are inaccurate and open to interpretation. The film erases the sharp categorical boundaries between fact and fiction, subjectivity and objectivity, male and female. The result is an original romantic comedy (something seldom seen in contemporary Hollywood cinema) that reveals the potential strengths and challenges of the genre.

References

Boggs, Carl and Tom Pollard. “Postmodern Cinema and Hollywood Culture in an Age of Corporate Colonization.” Democracy & Nature, 7:1 (2001): 159-181. Print.

Brooks, Xan. “Special relationship: why is Miramax so willing to give Tarantino $55m and carte blanche for his new movie?” in The Guardian. July 18 (2003): 11. Print.

Ebert, Roger. “Review: 500 Days of Summer.” Chicago Sun Times. Rogerebert.suntimes.com, July 15, 2009. Web. 4 November 2010.

Freer, Ian. “(500) Days of Summer.” Empire, n.244 (2009): 62. Print.

Hillier, Jim. “US Independent Cinema Since the 1980s.” in Contemporary American Cinema. ed. Linda Williams and Michael Hammond. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006: 247-264. Print.

Jeffers McDonald, Tamar. “Homme-Com.” in Falling in Love Again: Romantic Comedy in Contemporary Cinema. ed. Stacey Abbott and Deborah Jermyn. London: I.B. Tauris, 2009: 146-159. Print.

King, Geoff. Indiewood, USA – Where Hollywood Meets Independent Cinema. New York: IB Tauris, 2009. Print.

Neustadter, Scott & Michael H. Weber. (500) Days Of Summer: The Shooting Script, intro by Marc Webb. New York: Newmarket Press, 2009. Print.

Ordona, Michael. “Review: (500) Days of Summer.” Los Angeles Times. Latimes.com, July 17. 2009. Web. 4 November 2010.

Patterson, John. “End of the indie?” in The Guardian. July 18 (2008): 2. Print.

Stables, Kate. “Review: (500) Days of Summer.” Sight and Sound, 19.9 (2009): 64. Print.

Stam, Robert. Film Theory: An Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000. Print.

Thompson, Anne. “Sly Fox.” New York Magazine. Nymag.com, June 21. 2003. Web. 4 November 2010.

Wiseman, Eva. “Is there such a thing as ‘the one’–and what happens if you lose her?” in The Observer. August 16 (2009): 11. Print.

Written by Harry Ryan (2010); edited by Guy Westwell (2011), Queen Mary, University of London.

This article may be used free of charge. Selling without prior written consent prohibited. Please obtain permission before redistributing. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2011 Harry Ryan/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post