Plot Louisiana, the present. While defending his pregnant wife from attack US Army Ranger Cameron Poe accidentally kills a man. Imprisoned for seven years, he learns Spanish and origami, not allowing his wife or daughter to visit him during his incarceration. He hitches a ride on a prison transport plane at the time of his release, but the plane is taken over by well-prepared life criminals led by Cyrus “the virus” Grissom. Poe chooses to stay on board when he has a chance to leave in order to protect a female prison guard and his sick friend. The plane is tracked from the ground by US Marshall Vince Larkin, who believes Poe to be an ally, although his superiors are sceptical. Poe continues to ingratiate himself with the ring-leaders of the takeover and manages to get a message to Larkin. The plane lands at Lerner Air Field and a confrontation between the military and the convicts takes place. The prisoners escape in their plane, and Larkin convinces others not to shoot it down. Damaged, the plane proceeds to crash land on the Las Vegas Strip. Poe and Larkin join forces to chase down Cyrus and others who have escaped. Poe is finally reunited with his wife and meets his daughter.

Film note The action genre is one of the most consistently successful forms of Hollywood film, and has in Jose Arroyo’s words “become such a popular type of cinema as to be almost synonymous with it” (viii). However, the critical attention paid to such films does not match their ubiquity. For Eric Lichtenfeld studies of the action genre are imprecise at best, thanks to the films being “taken for granted” (6). Con Air is a superlative example of a particular type of action film prevalent in the 1990s, like many of its ilk it was widely seen and popular with audiences, but also “taken for granted” and dismissed as spectacular nonsense. Yet the tone of the film, its treatment of masculinity and its depiction of the US are all intriguing, nuanced and deserving of analysis.

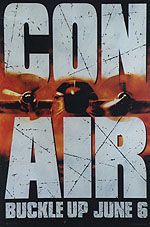

Released in 1997, Con Air is positioned by Manohla Dargis as the debased alternative to Face/Off (1997), a film she deems problematic but superior, accusing certain injudicious critics and audiences of being unable to tell the difference between the two (69–70). The basis for comparison is certainly strong: both Con Air and Face/Off were released in June 1997, had similar production budgets of $75m and $80m, and similar worldwide box office returns of $224m and $245.6m respectively. They also both star Nicolas Cage in a lead role and were R-rated in the US market. It seems the presence behind the camera on Face/Off of Hong Kong auteur John Woo marked that film out for Dargis as distinct from the generic American product represented by Con Air, directed by Simon West and produced by Jerry Bruckheimer. However, while offering an explicitly “blue-collar” alternative to Face/Off’s well-to-do cops and criminals, Con Air demonstrates a shrewd intelligence that belies its commercial aesthetic, in doing so presenting a more complex portrait of both the action genre and the US than offered by Woo’s balletic gunplay.

West, making his first feature film after well-received commercials for Pepsi and Budweiser, was one of a long line of directors shepherded by Bruckheimer from television advertising to mainstream film-making (notable others being Tony Scott and Michael Bay). Bruckheimer, along with Don Simpson (who died in 1996), had defined the action film landscape of the late-1980s with flashy visuals and fast-paced editing, and there was much in common with the style of their films and the music videos on popular new channel MTV (which first aired in 1981). Philip Drake calls Simpson and Bruckheimer “exemplary exponents of the high concept philosophy”, the “high concept” being a film pitch that could be sold to viewers with a single short sentence, such as Con Air‘s “Die Hard on a plane, with convicts” (69). Janet Maslin, in her review for The New York Times, notes the strengths and weaknesses of such a philosophy: “Thrill rides don’t often make more sense than beer commercials, which they stylistically resemble by insisting that every frame look slick and pack a visual wallop … [Con Air has] the prettiness and polish of advertising art”.

“Make a move and the bunny gets it” In the 90s, high concept was usually coexistent with muscular white male heroes, explicit but often comic violence and frequent profanity. This was an avowedly commercial recipe, which Bruckheimer cannily adapted for family audiences in the 2000s by jettisoning the more violence and toning down the ripe language. Indeed, the genre as it stood was showing signs of exhaustion in the early 1990s. Jonathan Romney sees in Last Action Hero (1993) (in which Arnold Schwarzenegger plays himself as a preening self-promoter), the “drastic exhaustion” of a form that has “run through all its possibilities” and so can offer no further surprises (38). Con Air, no less self-aware than Last Action Hero offers the same parodying of action film conventions that had become standard expectations of the genre, but does so at a higher pitch. When the hijacked plane picks up a classic car during take-off, the 1967 Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray soaring through the sky, the protagonist Cameron Poe surveys the scene and comments, “On any other day that might seem strange”. Whereas the overblown and melodramatic excess of Dargis’s preferred Face/Off can be critically linked to the operatic style of Hong Kong action films, the hyperbolic stylistics of Con Air indicate its debt to, critical stance upon, and renewal of, the ironic and self-referential tendency of its own genre.

According to Dan Harries, parodies and film spoofs work to “simultaneously critiqu[e] established genre codes while also serving to sustain and reconstitute these codes”, making spoofs “the most condensed and crystallized instances of a given film genre today” (281). Con Air, then, functions in a similar manner to a spoof: generic trademarks like hostage-taking are mocked when the villain brandishes a gun against the head of a children’s toy bunny rabbit and threatens “make a move and the bunny gets it”. But this mockery reasserts the validity of the conventions: the bunny has been stressed as a signifier of Poe’s waiting family and his return to a normal life. The image of a gun against the head of a stuffed toy is incongruous and played for laughs, but the importance of the bunny to the narrative means this scene also functions dramatically. The parodic exaggeration of spoof films is a mechanism for “generating difference that inevitably leads to reaffirmation” of generic codes (Harries 284). Con Air reaffirms generic codes by simultaneously undermining them: Poe learning origami during a seven-years-in-prison montage; the overwrought death of villain Cyrus Grissom, involving laceration, execution, and beheading; and son on. Anthony Lane’s labelling of the aforementioned bunny as a “Wagnerian leitmotiv” indicates the extent to which these parodic elements are integrated into the narrative and treated with an earnestness that revitalizes them as viable dramatic units (rather than comic set-pieces) (188).

Man-on-man action A consequence of this knowing take on genre conventions is that Con Air provides a more challenging presentation of masculinity than found within what is an often conservative film form. In comparison to films such as 25th Hour (2002), in which the primary threat of the story is that of (seemingly inevitable) sexual assault during imprisonment in the American penal system, or even casual references to jail-based anal rape in more light-hearted films like The Rock (1996) and Deja Vu (2006), Con Air avoids representing maximum security incarceration as an environment infused with sexual perversion and constant homoerotic threat. As Pamela Church Gibson notes somewhat slyly with respect to Face/Off, it is common for action films to feature “men who are seen through their ‘desire’ for another man, whatever form that desire may take” (186). The genre presents male mastery, but in doing so inevitably offers up the male body, usually in direct comparison and engagement with other male bodies, for spectacular contemplation. To cope with this, action films normally show overt suspicion and disrespect towards alternative sexualities, from the crass stereotyping of a gay hairdresser in The Rock to the clear sexual perversion of villain Commodus in Gladiator (2000). This serves as a tactic for the affirmation of the masculine (read: heterosexual) primacy of the protagonist(s) of such films.

In Con Air transsexual convict Sally-Can’t-Dance is treated with respect and allowed to express feminine traits within the group without being threatened. When she attempts to attack Poe he clearly considers a violent punch (as he has just delivered to another male prisoner), but slaps her instead, engaging with her on her own terms. There are many other examples in which appreciation of masculinity between men is accepted, and even permitted to exist on a potentially sexual basis. An undercover DEA agent describes a prisoner as a “good-looking brother” and Alpha-male Cyrus is openly fawned over by other convicts, and they become jealous when Poe begins to be the magnet for Cyrus’s appreciative comments and gazes. More overtly, Poe makes his closest friend during incarceration by offering him pink ball-shaped coconut sweets (an explicit marker of homosexuality in the eighth season episode of The Simpsons (1989–ongoing) titled “Homer’s Phobia”). These examples all indicate the manner in which the film overtly presents a homosocial masculine culture that is comfortable with the expression of what might be termed “gay-coded” traits, traits which are usually pilloried in other films of the genre.

Such characters and moments should be seen in relation to the hyper-masculine arena of law enforcement. DEA Agent Duncan Malloy is loud, brash and wrong-headed: his rage prevents him from approaching the situation logically and so allows him to fall for Cyrus’s diversion of a false transponder (this anger notably stemming from the murder of a man he cared about). Malloy surrenders his love for his phallic, and destroyed, automobile in an act of friendship with another male character, Vince Larkin, and states he was “bored of that car, anyway”. Larkin’s co-worker Ginny, a potential love-interest, is shown at the start of the scene in a twinned shot with Poe’s wife, stressing the omission of a scene in which her and Larkin pair-off. While Poe is reunited in the closing scene with his family in a gaudy and uncomplicated tableau of affection, Malloy and Larkin bond as the former’s volatile assertion of masculinity is tempered and softened.

This said, protagonist Poe is aligned throughout with standard conceptions of family through the existence and beauty of his waiting wife and their angelic daughter, his flirting with Cyrus and the others shown to be a façade. When psychopath Billy Bedlam discovers Poe has been disingenuous about the length of his sentence, the scene conflates the discovery of the lie with the revelation of Poe’s explicit heterosexuality: a letter from Poe’s daughter. In pretending to be a life-criminal, Poe must cover up his normative sexuality, and the aforementioned final embrace of Poe’s family asserts the correctness of Poe’s nuclear family unit. Furthermore, the elements cited above could be interpreted as strategies to stress the “otherness” of the criminals, and as ultimately proved “incorrect” within the value schema of the film, or played primarily for laughs. Nonetheless, the sustained depiction of such a homosocial group works to narrativize and emphasize the possibility of the action film to offer “homosexual and heterosexual economies of consumption of the male form”, as identified by Lisa Purse (101). The action genre is historically a “men only” zone, but the consistent displaying of athletic male bodies and intense (and often physical) male-on-male interaction makes a purely “straight” reading or audience position problematic, a consequence Con Air cannily works with and subverts. Such playfulness is bound up in the tone of the film, which as we have seen works hard to operate on the twin levels of the self-referential and the dramatically earnest.

The Postmodern United States of America This subversive intent can also be seen in the film’s depiction of America, and the American landscape. Taking place entirely in the South-Western US states of Nevada, California and Arizona, the film occupies the same environment as Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970), a movie of “stunning superficiality” according to Vincent Canby of The New York Times (words that could equally be applied to Con Air).

The protagonist of Zabriskie Point, Daria, having fled the over-stimulation of Los Angeles by driving into the desert, finds a quintessentially modernist architectural house in which corporate conglomerates are planning further encroachments into the desert in the form of tacky suburban neighbourhoods linked by freeways. Existentially enraged, Daria destroys this structure through force of will, the explosion shown dozens of times, its consequences lavishly exhibited in slow motion, her “baleful gaze” wanting to “destroy not only the things that so obsess America but all the scraps of its ideology” (Chatman 160). So too the ending of Con Air revels in borderline incomprehensible destruction, as the plane crash lands on the Las Vegas strip, finally coming to a halt in the lobby of the Las Vegas Sands Hotel. A subsequent chase concludes with the destruction of an armoured car full of hundred-dollar bills, which subsequently rain down upon the detritus of the vehicular carnage. These set-pieces indicate a nihilistic abandon that can be understood as an evolution, and exhaustion, of the revolutionary impulses at the heart of Zabriskie Point. The quintessentially US ideology of consumerism is damned equally in both, if via different strategies.

References to celebrity culture in Con Air (“I see among us eleven Current Affairs, two Hard Copies and a genuine Geraldo interviewee” says a guard of his charges) and confusion between the real world and that of television (“he makes the Manson family look like the Partridge family” one convict says of another) suggest that fame and violent sociopathy are analogous. In contrast to these gleeful, epithet-laden villains, Poe has a wife who works in a seedy bar and hopes his unborn daughter will grow up to be Miss Alabama. Blue-collar heroes are common in the action genre, but these facts make later labelling by other characters of Poe a “hill-billy” and “trailer-trash” somewhat accurate.

Las Vegas, a paradigmatic postmodern symbol, is where these “shitty white trash” prisoners end up. In The Cultural Turn, cultural theorist Fredric Jameson identifies the clash of high and low culture that predominates in “newer postmodernisms”, which are “fascinated precisely by that whole landscape of advertising and motels, of the Las Vegas strip, of the Late Show and B-grade Hollywood film” (2). Las Vegas, for Jameson as for other critics, is a symptom of the false and vacuous pleasures of consumerism. The city does not contain any viable historical memory, instead quoting global historical landmarks (the Eiffel Tower, the Pyramids), and in doing so acknowledging a wider world but denying its importance. Las Vegas creates a world of spectacle and bedazzlement in otherwise inhospitable territory, and suggests no alternative to knowing gaudiness–strategies echoed by Con Air. Earlier in the film, when asked where he is taking the captured plane, Cyrus states “we’re going to Disneyland” – a place French postmodernist Jean Baudrillard considers to be “the perfect model of all the entangled orders of simulacra”, a site of unconcealed artificiality which openly exists to “make us believe that the rest is real” (12). As with Disneyland, as with Vegas; Cyrus is more accurate than he knows about their destination.

In contrast to other action films in the 1990s like The Peacemaker (1997), Enemy of the State (1998) and The Matrix (1999), which all revel in the surveillance culture of the time (control rooms, cameras and screens dominating the mise-en-scène) Con Air presents a low-tech and high-junk version of the US. But this depiction is just as contemporary as the one shown in these other films. Zygmunt Bauman suggests that, in a globalised world, the “technological annulment of temporal/spatial distances” tends to polarize humanity into the mobile and immobile (18, italics his). Fittingly, he sees prisons such as Pelican Bay in California as quintessential sites of immobility and disenfranchisement, prisoners disconnected from each other and prevented from any productivity. So too the prisoners in Con Air attempt to escape confinement, but as a result are forced to exist within the empty space of the desert which, while “forty-nine minutes from anything resembling authority” according to Cyrus, is also an isolated and unproductive space. When they truly escape from incarceration it is by crashing into the vacuous postmodern space of Las Vegas.

In this way the film consolidates its bleak portrayal of the US in the 1990s, a parodic tone and incisive references to contemporary culture revealing the stark environment of the immobile residents of a globalized world. While more recent action blockbusters like the Bourne franchise (2002–2007) seek verisimilitude as a badge of relevance, Con Air jettisons verisimilitude for the purposes of more fully integrating its content of a critical stance upon the US with the highly particularized form of the action blockbuster film.

References

Arroyo, Jose. “Introduction.” Action/Spectacle Cinema. ed. Jose Arroyo. London: BFI, 2000. vii–xiv. Print.

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1994. Print.

Bauman, Zygmunt. Globalization: The Human Consequences. Cambridge: Polity, 1998. Print.

Canby, Vincent. “Review: Zabriskie Point”. The New York Times, 10 Feb. 1970. Web. 13 June 2011.

Chatman, Seymour. Antonioni: Or, The Surface of the World. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1985. Print.

Dargis, Manohla. “Do You Like John Woo?” in Action/Spectacle Cinema. ed. Jose Arroyo. London: BFI, 2000. 67–71. Print.

Drake, Philip. “Distribution and Marketing in Contemporary Hollywood” in The Contemporary Hollywood Film Industry. ed. Paul McDonald and Janet Wasko. Oxford: Blackwell, 2008. 63–82. Print.

Gibson, Pamela Church. “Queer Looks, Male Gazes, Taut Torsos and Designer Labels: Contemporary Cinema, Consumption and Masculinity” in The Trouble With Men: Masculinities in European and Hollywood Cinema. ed. Phil Powrie, Ann Davies and Bruce Babington. London: Wallflower, 2004. 176–186. Print.

Harries, Dan. “Film Parody and the Resuscitation of Genre” in Genre and Contemporary Hollywood. ed. Steve Neale. London: BFI, 2002. 281–293. Print.

Jameson, Fredric. “Postmodernism and Consumer Society” in The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings on the Postmodern, 1983–1998. London: Verso, 1998. 1–20. Print.

Lichtenfeld, Eric. Action Speaks Louder: Violence, Spectacle, and the American Action Movie. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2007. Print.

Lane, Anthony. Nobody’s Perfect. London: Picador, 2002. Print.

Maslin, Janet. “Signs and Symbols on a Thrill Ride”. The New York Times, 6 June 1997. Web. 14 June 2011.

Purse, Lisa. Contemporary Action Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011. Print.

Romney, Jonathan. “Arnold Through The Looking Glass.” Action/Spectacle Cinema. ed. Jose Arroyo. London: BFI, 2000. 34–39. Print

Written by Nick Jones (2011); edited by Guy Westwell (2011), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2011 Nick Jones/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post