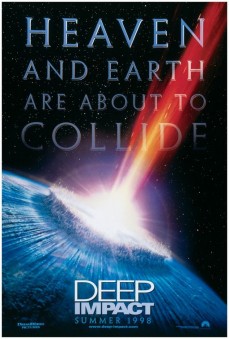

Plot Leo Biederman, a 14 year-old amateur astronomer, photographs an unknown object among the stars. His photo is checked by astronomer Marcus Wolf, who is killed in a car crash just after he realises the object is a comet headed for earth. A year later, television reporter Jenny Lerner scents a government scandal but discovers that an Extinction Level Event (ELE) is pending: President Tom Beck announces that the Wolf-Biederman comet is heading towards earth. An experimental spacecraft, the Messiah, is sent with veteran astronaut Spurgeon Tanner aboard to land on the comet and shatter it with nuclear bombs. Jenny, having become the leading newscaster, covers the mission on television. Tanner succeeds only in splitting the comet. With two comets now threatening the planet, the president announces that underground ‘arks’ will shelter a limited number of selected people. Leo marries his sweetheart Sarah to ensure she survives with him in an ark, but she won’t abandon her parents. Leo hunts for his young wife amid the crowds desperately fleeing the expected tidal wave, and Jenny gives up her own place in the ark to a colleague to await the end with her father. The smaller comet hits the Atlantic and the wave destroys New York. Reunited, Leo and Sarah manage to stay just ahead of the devastation by fleeing inland on a motorbike. In space, Tanner steers the Messiah into the remaining comet and blows it into harmless fragments (adapted from Strick 39).

Film note Hollywood is located in and around Los Angeles, a geological weak-spot prone to catastrophic earthquakes. Perhaps, then, it is no surprise that, “…from early biblical epics and 1950s science-fiction B-movies through to recent action/disaster/science fiction hybrids, scenes of mass destruction have proven a long standing and pervasive feature of [Hollywood’s] cinema of spectacle” (Keane 1). Susan Sontag writes that “from a psychological point of view, the imagination of disaster does not greatly differ from one period in history to another. But from a political and moral point of view, it does” (224). It is important, then, to find ways of locating the “imagination of disaster” within specific historical and social contexts in order to better understand its political and cultural significance. Hollywood movies like Deep Impact are one such way of doing this.

The imagination of disaster Ryan and Kellner note that “[t]he metaphor of catastrophe in such films permits anxieties to be avoided in their real form, but metaphor is itself a kind of aesthetic/psychological defence against threats to social ideals, a therapeutic turning away. It is through a deciphering of the metaphors by asking what they turn away from, therefore, that those symptomatically absent sources of anxiety can be deduced” (51). So, why is disaster such a significant metaphor in the late 1990s? And from what does disaster as metaphor allow Americans to turn away? There are a range of possible answers to these questions: first, in the post Cold War political universe the US has run out of formidable enemies against which to define their national purpose and sense of identity. As such, disasters offer a version of “clear and present danger”. Second, in the 1990s the US government proposed the building of a Strategic Defence Initiative (initially called “Star Wars” by Reagan in the 1980s) to protect against nuclear missile strikes. This desire to find hard and fast solutions (such as SDI) to simplistically defined foreign policy situations (nuclear attack by a nation state) is representative of America’s turning away from the ever more complex and compounded foreign policy situations around the world that are non-state based and rely on terrorism as their primary tactic. Disasters offer a “hard” problem (like nuclear weapons) that can be tackled rather than a “soft” problem (like dispersed terrorism) that is very difficult to tackle. Third, there are considerable environmental fears and general anxiety that finite resources (oil, clean air, rare species) are quickly disappearing. Disasters offer an extreme version of the nature bites back fantasy. Fourth, in the 1990s the US suffers a loss of political direction. In the recent 2000 election those Americans who could be bothered to vote (less than 50%) couldn’t decide who to vote for (resulting in a hung decision between the Republican George Bush Jnr. and Democrat Al Gore). The election indicates that it is becoming increasingly difficult to identify any kind of coherent, democratic support for the conventional political process. Disasters provide a galvanising event in the face of which consensus is renewed and democratic politics redeemed. No doubt all these factors have a bearing, the first two (America’s uni-polar global position and its desire for simple solutions to blunt threats) have now been brought to the fore by the 9/11 terrorist attacks. However, I wish to argue that it is a more general political anxiety which pervades the narrative of Deep Impact and which posits the meteor as a catalyst that will precipitate a renewal of faith in the system.

Although religious metaphor is rife in the film (the federal government build an “Ark” to ensure the preservation of the American way of life; the craft sent to destroy the threat is titled “Messiah”) there is little indication that the tidal wave/flood is the judgment of a God grown weary of corrupt humankind. The society that pre-exists the arrival of the comet is portrayed as fundamentally decent, stable and desirable. Deep Impact requires us to believe that the Extinction Level Event threatening humankind is simply an accident. The aim is survival and the protection of the system as it stands all costs. This requires members of society, as presented by the film’s narrative, to “pull together”. At the beginning of the movie the media industry is shown to be cynical and hard-bitten (“I know you are a reporter, but you used to be a person”) but ultimately the media professionals redeem themselves through their careful handling of the crisis. Politics is shown as a difficult and lonely but ultimately honest job and American high-school students (who would become a problematic social group to present following the Columbine shootings in 1999) play a central role in spotting the meteor and ensuring the survival of humankind. Whereas the narrative of 1974’s paradigmatic disaster film The Towering Inferno is governed by conflict and chaos resulting from a corrupt building contractor (read by many commentators as a microcosm of a corrupt American society), the narrative of Deep Impact is governed by reconciliation, propriety and renewal in the face of a natural disaster that brings (a select group of) people together.

An understanding of two cycles of disaster movies is required in order to properly contextualise Deep Impact. The first cycle consists of 53 movies made throughout the 1970s including Airport (1970), The Poseidon Adventure (1972), The Towering Inferno and Earthquake (1974). The second cycle consists of 56 disaster movies released in the 1990s, with fourteen films released in the peak year of 1997, and includes movies like Twister (1996), Independence Day (1996), Armageddon (1998) and Godzilla (1998) (Keane 73). Ryan and Kellner argue that the 1970s disaster cycle represented “…a return to more traditional generic conventions” and that it depicted ”a society in crisis attempting to solve its social and cultural problems through the ritualised legitimisation of strong male leadership, the renewal of traditional moral values, and the regeneration of institutions like the patriarchal family” (23). In their reading, disaster movies “…advocate corporatist solutions whereby an elite of leaders, usually professionals or technocrats, enable groups of people to survive through co-ordinated, even obedient action” (52). Clearly, Ryan and Kellner’s observations can be extended to the 1990s disaster cycle in general and Deep Impact in particular – the ritualised legitimisation of strong male leadership in Tom Beck’s calm but purposeful president, the renewal of traditional moral values via the regeneration of institutions like the patriarchal family and the imposition of technocractic, corporatist solutions, symbolised by a warm and caring but also ruthlessly efficient NASA.

In the eye of the storm: the nuclear family That said, there are also significant liberal undercurrents to Deep Impact that require any positioning of the movie as politically conservative to be modified. These liberal undercurrents can be seen most clearly in the movie’s portrayal of the family. Along with his pledge to salvage the shaky US economy in 1992, US president Bill Clinton articulated a pluralistic vision of family values: “an America that includes every family. Every traditional family and every extended family. Every two parent family, every single-parent family, every foster family” (Skolnick 2). In the movie’s most poignant image, an extreme long shot shows Jenny Lerner (a resourceful, but ultimately lonely careerist) and her father (who left his wife, Jenny’s mother, for a younger woman) standing arm in arm staring out to sea. As the tidal wave approaches they forgive past mistakes and reaffirm happy memories. Clearly the disaster is the catalyst for a reappraisal of life choices, the conclusion of which is an acknowledged regret over decisions that have placed the family in jeopardy. The surrounding calm of the beach echoes their inner peace (a location and tone established earlier in the film as the impending disaster triggers cathartic argument and desperate soul-searching) and as they disappear into the wave their serene acceptance allows them to transcend the widespread public panic sketched out in the disaster sequences. The propriety with which they accept their fate indicates the strength of the renewed family bond.

The tidal wave sequence interleaves the resigned acceptance of death by an older (dysfunctional?) generation and the survival of a younger generation who actively renew and reaffirm the nuclear family. Leo Biederman performs a chivalric rescue of his bride, Sarah Hotchner, in order to consummate their arranged marriage through conventional, male, heroic action. In doing so Biederman and Hotchner perpetuate the ideal of romantic love as the glue that holds family together, something their arranged marriage had momentarily called into question. Their relationship is also conveniently purified of the complexities of adult sexual relations and biological birth through the adoption of Hotchner’s mother’s child. Clinton’s shrewd politics accepts all families but Deep Impact clearly shows that the logic of Hollywood still prefers a more traditional model. As a review of Twister, another key film in the late 1990s disaster cycle, puts it, “…in the eye of the storm we reassuringly find the nuclear family” (Arthur 73).

New York and global apocalypse My reading of the film thus far has placed the movie within a specifically American context. Yet, to understand Deep Impact fully, it is necessary to go beyond this context. Profits for Hollywood movies in the mid- to late-1990s are just as likely to come from overseas as from domestic ticket-sales. American movies must satisfy, or at least accommodate, an incredibly wide-range of viewers of differing nationalities. Paul Arthur offers a snapshot of the cult of the millennial disaster, a cult that extended across national boundaries: “…cheesy FX dramas from Tidal Wave to the recent Meteorites, a Nova special on ‘The Doomsday Asteroid’, and an assortment of science programs screened on A&E or the Discovery Channel featuring fault-lines, Mount Pinatubo, and other alarming conditions that demonstrate, in the words of one solemn narrator, ‘how vulnerable and ill-prepared we are for the Big One.’ Even the Weather Channel got into the act with seasonally adjusted programming around El Nino, ‘Tornado Alley’, and other hot spots” (75). Clearly the films of the disaster cycle of the 1990s–especially Independence Day and Armageddon–are part of this trend. Put simply, millennial disaster, like the action movie genre that preceded it, travels and translates well.

Alongside the general theme of millennial disaster other aspects of the movie can be read as attempts to secure non-American audiences. The movie capitalises on America’s other key export–television. We inhabit the narrative via the television professionals, politicians and suburbanites and they inhabit their world via TV sets and satellite links. Television is the central expository device of the narrative with the global (though clearly American) communications industry–from NASA to MSNBC–providing a unifying and ordering framework for the movie’s action. Director Mimi Leder’s career in television, as director and producer of ER (1994-2009) and other US TV shows, might also be significant in this respect. Deep Impact’s cast includes recognisable faces from ER and the narrative pace of many of the non-meteor related sequences owe much to television aesthetics. Strick notes this fact with irony: “These are not acquaintances to be washed away by a mere mile-high tidal wave. They’ll be back next week in some other episode old or new. Even in the meteoric rush of television, survival is written upon them” (40).

The central importance of the city of New York to the 1990s cycle of disaster movies, appearing in Deep Impact, Godzilla, Daylight (1996), Independence Day, Armageddon, AI (2001), The Siege (1998) and The Peacemaker (1997), should also be seen in the light of an increasingly globalised market for Hollywood’s movies. New York is the most familiar of American cities for non-Americans. As Stephen Keane writes: “Over-populated and microcosmic, New York is the modern metropolis par excellence. Its skyline is instantly recognisable, the buildings proudly and arrogantly ‘scraping’ their identity into the very atmosphere. It could well be that the sheer familiarity of certain cities makes them the ideal target for disaster movies. It is in this sense, for example, that they enter into the shorthand geography of end-of-the-world films” (101).

New York’s identity as a city of immigrants ties American history to the histories of many other countries around the world. The Statue of Liberty (obliterated and beheaded by Deep Impact’s tidal wave) is a profoundly American symbol but also one which plays a significant role in the mythology of the immigrant and America as a land of opportunity and as cultural “melting pot”. Clearly, we experience the comet strike from the subjective point-of-view of the movie’s avowedly American citizens but the use, alongside this subjectivity, of an omniscient camera and the focus on the landmark cityscape of New York encourages us to understand the movie within a global framework.

The logics of a global Hollywood are necessarily contradictory and may sit uncomfortably with readings of the movie that locate it in relation to specifically American anxieties and desires. The events of September 11 have clearly indicated the extent of anti-American feeling in many countries and it may be that for many non-American viewers there is genuine pleasure to be had in seeing the destruction of American cities and citizens. I do not want to argue that this is the preferred reading of the movie only that Deep Impact clearly makes available scenes of mass destruction that some viewers may find pleasurable. The movie allows for this contradictory response whilst at the same time offering renewal and reaffirmation of certain American “core values”.

In conclusion, then, Tom Beck, America’s first black president, is calm, reasoned and untarnished as he presides over a global disaster. The disaster is dealt with via a combination of strong male leadership (Beck, Biederman and Tanner), the resolve and renewal of the white, middle-class, American “nuclear” family (the Lerners, the Hotchners and the Biedermans) and American self-sacrifice (the multi-ethnic crew of the Messiah whose final act is to say goodbye to their families). The movie attempts to renew faith in the American political process and in American national identity. At the same time it works to satisfy a global audience whose relationship with America, as the events of September 11 have shown, may be qualified and contradictory.

References

Arthur, Paul. ‘Unnatural Disasters.’ Film Comment, 344 (1998): 72-75. Print.

Hoberman, J. ‘Apocalypse Now and Then: A Short History of the Cinema of Catastrophe.’ The Village Voice, 4318 (1998): 70, 72, 75. Print.

Keane, Stephen. Disaster Movies: The Cinema of Catastrophe. London: Wallflower, 2001. Print.

Ryan, Michael and Douglas Kellner. Camera Politica: The Politics and Ideology of Contemporary American Film. Bloomington, IA: Indiana University Press, 1990. Print.

Skolnick, Arlene. ‘Family Values: The Sequel’ in The Prospect, 8.32 (1997): 86-94. Print.

Taubin, Amy. ‘Playing It Straight – Independence Day is a Post-Rodney King Feel-Good Disaster Movie.’ Sight and Sound, 7.7 (1996): 6-9.

Sontag, Susan. Against Interpretation and Other Essays (London: Andre Deutsch, 1965): 209-25.

Strick, Philip, ‘Review: Deep Impact.‘ Sight and Sound, 8.7 (1998): 39-41.

Written by Guy Westwell (2001); edited by Nick Jones (2011), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2011 Guy Westwell/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post