Plot Iraq. Present day. Staff Sergeant William James joins a bomb disposal team after the death of his predecessor. James defuses a large IED and makes safe a car bomb at the UN headquarters. With only 38 days left in their rotation, the two other team members, Sergeant JT Sandborn and Specialist Owen Eldridge, are wary of James’s unorthodox and reckless approach. James befriends an Iraqi boy nicknamed Beckham. Eldridge informs Army doctor Colonel John Cambridge that he suffers from intrusive thoughts about dying. Sandborn and Eldridge consider killing James in order to protect themselves from his errant risk-taking. Back at base, and after a fierce encounter with insurgents, the men drink whisky together and wrestle. The team is sent to make safe a bomb-making factory where they find Beckham has been killed and his body rigged with explosives. Leaving the factory, Cambridge is killed by an IED. Angry at Beckham’s death and appalled by the aftermath of an oil tanker bombing, James persuades Sandborn and Eldridge to hunt down the insurgents responsible. A haphazard encounter with the enemy results in Eldridge being injured by friendly fire. As he is evacuated he blames James for his injuries. James and Sandborn unsuccessfully attempt to save a man who has been forced to wear a suicide bomb vest. Their rotation over, James returns home to his wife and infant son but finds it hard to adjust and returns to Iraq.

Film note A significant cycle of feature films has been released relating to America’s current wars, including (in order of theatrical release): GI Jesus (2007), The Situation (2007), Home of the Brave (2007), In the Valley of Elah (2007), Lions For Lambs (2007), Redacted (2007), Badland (2007), Grace is Gone (2008), Stop-Loss (2008), The Lucky Ones (2008), The Hurt Locker (2008), The Objective (2009), Brothers (2009), The Messenger (2010), and Green Zone (2010). The release dates of these films coalesce around winter 2007-08, and most are set in the period of adjustment following the Iraq invasion, when jingoistic “mission accomplished” rhetoric confronted the reality of a strengthening insurgency and breaking news of the lack of WMD and prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib. This difficult and politically fraught period presented filmmakers with limited opportunities for positive formulations of the war, and many of the films depict atrocity, suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder and the general stalemate of the war on the ground. Poor box office returns clearly show that US audiences did not relish the opportunity to journey into the dark heart of the war in Iraq.

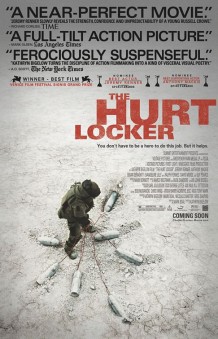

The Hurt Locker is a notable exception to this general trend. Initially held back as the film’s producers attempted to figure out how to sell a war movie to filmgoers interested in anything but, the film then took a long, award-winning tour round the festival circuits in 2008/early 2009. As a result of good word of mouth and favourable reviews the film was picked up by distributor, Summit Entertainment, and given a wide release in the US from June 2009, eventually showing in 535 cinemas and grossing $48.6m worldwide (with roughly two thirds of the film’s profits coming from non-US markets). The film was nominated for nine Academy Awards in 2010 and won six including Best Picture and Best Director for Kathryn Bigelow, the first woman to win in this category. The Hurt Locker also earned numerous awards and honors from critics’ organizations, festivals and groups worldwide, including six BAFTAs. Problems with widespread internet piracy notwithstanding, as of August 2010 US sales of the DVD had reached $30.3m (Allen). So, in a difficult climate for war movies, what made The Hurt Locker so successful?

Roadside bombs and redemption Part of the answer to this question can be found by examining the film’s close correspondence with the World War II propaganda film. Unlike its critical and challenging counterparts, the film offered an exciting, positive view of the war, something audiences and critics responded to as an antidote to the general media coverage of a war going bad.

During World War II, the war movie functioned as propaganda and became one of Hollywood’s staple genres. In support of a strident, jingoistic nationalism, the war movies of the 1940s celebrated individual and group heroism, the self-sacrifice of individual desires to higher ideals, and the effectiveness of military command and technology. The cultural imagination of war via the war movie was also governed by a severely restricted point of view (usually via the experience of a small military unit or squad) and the prejudicial construction of cultural otherness. A grim, bloody realism was also an essential part of the formula, reminding the viewer that the nation is built on the honourable sacrifice of young, citizen soldiers (Boggs and Pollard 13-15). After the war, these propagandist elements (what Thomas Schatz calls “Hollywood’s military Ur-narrative”) remained central to the genre, with even the bloodiest war movies tending to show war as a “progressive” activity, entered into reluctantly but ultimately necessary and productive (75).

Most scholars tend to agree that the war movie genre maintains this propagandist view of war until the late 1960s and 1970s, when the experience of being on the losing side in Vietnam causes something of a short circuit, leading films such as The Deer Hunter (1978) and Apocalypse Now (1979) to challenge and question many of the genre’s core myths (though they never manage to escape them completely) (Boggs and Pollard 90-91). However, after this brief cycle of what might be considered critical (if not resolutely antiwar) movies, the genre (and the positive view of war enshrined in it) rallied. Vietnam was increasingly constructed as an a-historical nightmare registered primarily through the experience of the ordinary combat soldier and this paved the way for a series of revisionist war films–from Coming Home (1978) to the Rambo trilogy (1982-1988)–that sought to alleviate the traumatic experience of the veteran and in doing so restore the credibility of war (Sturken 85-122).

As a result of this (and wider processes of cultural forgetting), a cycle of films in the late 1990s and early 2000s–including Saving Private Ryan (1998), Pearl Harbor (2001), and We Were Soldiers (2002), and sometimes referred to as the “greatest generation” cycle–was again able to present war in ways proximate to the propagandist genre staples of the 1940s (Boggs and Pollard). This reclamation of war as noble, positive and necessary prompted Mark Bacevich to argue in The New American Militarism: How Americans Are Seduced by War, that “…Americans in our own time have fallen prey to militarism, manifesting itself in a romanticized view of soldiers, a tendency to see military power as the truest measure of national greatness, and outsized expectations regarding the efficacy of force” (2). Bacevich claims that this “militarized” public sphere, with the war movie genre just one part of a wider culture that has fostered a revisionist, mythologized, and nostalgic view of war since the 1980s, primed Americans to respond enthusiastically to the belligerent rallying cries of their political leaders in the aftermath of 9/11. Many of the latest cycle of war movies–The Situation, In The Valley of Elah, Redacted–can hardly be said to offer a propagandist view of war. But what of The Hurt Locker?

Joshua Clover argues that The Hurt Locker’s loose, repetitive narrative structure emulates the aimlessness of the invasion and occupation, and the ultimately impossible task of imposing order. He compares the film to the HBO television series, Generation Kill (2008), which he suggests has an “episodic aimlessness” that “…summons up the unnarratability of the Iraq adventure, its unreason, and inevitably the idea that there was no reason to start with” (Clover 9). Counter to this, and against a backdrop of news reporting in which the war had become, according to Susan Carruthers, “just one damn IED after another,” Bigelow’s instinct is to repeat the bomb disposal scenario, each time using the resources of a fictional narrative to find a more redemptive line (73). As such, each act of bomb disposal is replete with the potential to redeem the experience of roadside bombs, military stalemate and steadily growing casualty figures. The bombs James defuses, for example, prevent a UN building and its civilian workers from being destroyed (we might recall that the UN headquarters were bombed in Baghdad in August, 2003) and he attempts to save an innocent Iraqi, press-ganged into being a suicide bomber. Most dramatically, he risks his own life to prevent the desecration of a dead child’s body. The underlying humanitarian impulse behind each of these acts leads Taubin to describe James as a conventionally heroic “equal opportunity saviour” and it is clear that not one of these sequences shows an IED in its most commonly used scenario: as a roadside bomb targeting US convoys (35).

Through his instinctive commitment to effective action James offers a corrective to the inertia that had come (by 2004) to typify the stand-off between heavily protected US forces (only vulnerable when moving by road) and the guerrilla tactics of the insurgents. James’s work of bomb disposal retains and reclaims a sense of the heroic, effective US soldier who puts his life at risk in pursuit of a mission informed by a moral imperative. In addition to this, in the film’s one conventional combat sequence, James behaves effectively, commanding his men and prevailing over the enemy. The tagline for the film reads: “You don’t have to be a hero to do this job. But it helps”.

There is also here an extension of the logic described by Susan Faludi in The Terror Dream, in which the narrative trope of rescue became a key mechanism for dealing with the experience and aftermath of 9/11, with the emergency services lauded as heroes, and with their commitment, obedience, and bravery dovetailing with a wider culture of jingoism that consolidated the move to war. Like these other heroes of 9/11, James is not mired in atrocity, nor even actual combat, but is instead actively attempting to save lives and establish order. As Slavoj Žižek puts it: “This choice is deeply symptomatic: although soldiers, they do not kill, but risk their lives dismantling terrorist bombs destined to kill civilians–can there be anything more sympathetic to our liberal eyes? Are our armies in the ongoing War on Terror, even when they bomb and destroy, ultimately not just such EOD squads, patiently dismantling terrorist networks in order to make the lives of civilians everywhere safer?”.

“There’s lots of eyes on us” In The Hurt Locker the choice of which events to depict, the positive characterization of James as hero and the symbolic meaning of his actions as redemptive are all is augmented through an extremely narrow and limited point of view system. Through clever direction and careful technical choices (the latter the work of Barry Ackroyd, Ken Loach’s long-time cinematographer) the viewer is immersed in the action alongside the bomb disposal squad. For example, the film’s opening sequence shows James’s predecessor, Staff Sergeant Matt Thompson (Guy Pearce) defusing an IED. A point of view shot from inside his heavy protective helmet fully immerses the viewer in the experience of bomb disposal. As he walks down the road distorted sound foregrounds his nervous breathing and a handheld camera pans from left to right to show us what he sees. Thompson doesn’t survive the opening sequence but our positioning in this scene is indicative of the orchestration of point of view in the film overall (the pattern continues as James replaces Thomspon as key focalizer) and of Bigelow’s desire to depict the experience of fighting in Iraq (in her words, “a war of invisible, potentially catastrophic threats”) through a tight focus on the experience of the combat soldier (Bigelow qtd. in Macaulay 33).

The film’s large sets (often in excess of 300m in size) were designated as “360 degree active”, with up to four camera operators given license to roam around the central bomb disposal event and shoot footage as they saw fit. As Alpert notes, a consequence of this is that “Throughout the film Bigelow shows us all perspectives — a shot from behind Iraqi snipers or a videographer taking pictures of Eldridge, a close-up of the eye of the cab driver focusing on James holding a pistol on him, a long shot of James’s squad from behind the bars of a window, a foreshortened close-up of a white building seen through the scope of a rifle, or a helicopter seen high above through the visor to Thompson’s helmet. “There’s lots of eyes on us,” Sanborn says at one point with fear in his voice.” However, these frantic cutaways, appearing in the heat of the film’s action sequences, are commonly point of view shots looking on at James and his men from diegetically unanchored positions (using techniques that harness the unsettling potential of off-screen space). On occasion these point of view shots are embodied but they remain at all times thoroughly decontextualized, with no attempt at characterization. The effect of these cutaways, then, is to make the threat more apparent: when the film switches back to seeing through the bomb squad’s gun sights, the viewer, like James and his team, feels under surveillance from all quarters.

Robert Sklar argues that this orchestration of point of view is reinforced by the fact that the Iraqis in the film are represented in prejudicial terms. Most Iraqis are seen at a distance (often through the sights of a rifle) and in the small number of sequences where characters come into focus–James’s standoff with a taxi driver, his surreal conversation with an academic who claims to work for the CIA–the film does not convey any clear information. Presumably this is intended to reflect the difficulty James faces trying to make sense of the war but it also has the effect of casting all Iraqis as inscrutable, masked and potentially dangerous. In perhaps the most powerful dramatic line through the film, James befriends an Iraqi child, nicknamed “Beckham”. As a result of his friendship with James, Beckham is kidnapped and killed and his body is discovered stuffed with explosives surrounded by the paraphernalia of Islamic fundamentalists. In the absence of any reporting of similar cases or of any imaginable strategic purpose to the preparation of a body bomb of this sort, this scene seems designed to symbolize the absolute barbarity and inscrutability of the enemy, as well as positing Iraq as a civil struggle (with Iraqi killing Iraqi) in which America has a role only as an unwitting and well-intentioned catalyst. James later sees Beckham (or a child who looks very like him) alive and in his confused response we are shown something of the way in which US forces struggle to even mark out one person from another, to them all Iraqis look alike.

By such means a reversal of power relations is effected, with the Americans portrayed as imperiled, powerless and victimized, in contrast to the realities of the balance of power between an insurgency and the world’s most powerful army. This sense of restricted point of view is reinforced by the way in which the film isolates the squad from wider military command structures. Hunter notes, for example, that their support and intelligence systems are rendered “…almost as shadowy nuances” (Hunter 78). The film is interested in combat but chooses not to show the chain of command, a decision that absolves it from drawing attention to how soldiers’s actions on the ground are governed, in part, by decisions taken by their superiors and politicians and policymakers in the US. Reviewing the film in The New Yorker, David Denby writes that this has the effect of narrowing “…the war to the existential confrontation of man and deadly threat” allowing it to be enjoyed “…without ambivalence or guilt” (84). Denby’s comments indicate how the film’s orchestration of point of view licenses a detachment from the wider discourses pertaining to the war, a detachment that limits understanding and allays critique.

By way of contrast, other films in the cycle do offer alternatives: the restricted point of view that governs the investigation at the heart of In the Valley of Elah ensures that the question of what can be known and how remains open and difficult; Redacted offers multiple perspectives as a defining principle of its construction; finally, Green Zone and The Situation strive towards a form of limited social realism, with narratives that attempt to triangulate between the different perspectives of Americans, Iraqis, soldiers, civilians, men, women, and so on.

Post-traumatic stress disorder At the time of the production of The Hurt Locker the war in Iraq was far from over and there was no obvious way in which (especially in fictional, dramatic terms) the war provided filmmakers with an obvious ready-made ending. So, how does The Hurt Locker negotiate this irresolution? The answer to this question revolves around the description of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the possibility of a therapeutic cure for this condition. As stated, James is presented in fairly conventional heroic terms but he is also shown to be suffering from PTSD–he is addicted to war, disobeys orders and is prone to lapses of judgement. Crucially, James’s combat stress is not triggered as a result of being a perpetrator of, or a witness to, atrocity (as is the case in a number of films in the cycle), but is instead a result of the incremental day-to-day strain of saving lives and helping people. The US is figured here as an irrepressible, skilful, decent young man harmed as a result of his desire to do good. Žižek argues that this delineated focus is “…ideology at its purest: the focus on the perpetrator’s traumatic experience enables us to obliterate the entire ethico-political background of the conflict”.

In an article for The New York Times, A.O. Scott tracks the widespread denial of politics/ideology in Iraq war movies and argues that this is a consequence of a focus on PTSD. Such a focus leads to the Iraq war (like Vietnam before it) being reduced in the American public sphere to a thoroughly psychologized (rather than suitably historicized) experience. The focus on PTSD allows a redemptive narrative of therapeutic healing to be brought to bear, a narrative that we have seen before in recuperative war movies such as Coming Home (1978) and Courage Under Fire (1996). These films show that trauma can be worked through, that masculine capability can be re-established (often via the love of a good woman) and that the honourable hard work of soldiering can be reclaimed and remythologized.

At first glance, a move towards resolution of this sort doesn’t seem a key feature of The Hurt Locker. James returns from Iraq and–confronted with the glossy surfaces of US consumerism and the grinding chores of family life–he confesses to his infant son that he only loves one thing, and in the next shot we see him striding towards an unexploded bomb. However, the refusal of the therapeutic move and the return to war feels provisional, more like a temporary deferral; it is significant that James is divorced but living as if married, almost as if the structures are remaining in place, ready for him to be reintegrated (if his wife would only listen and understand him, for example). While Bigelow strikes a provisional note, the redemptive ending proper can be seen in Brothers: at the film’s end Captain Sam Cahill (Tobey Maguire) finds the courage to tell his wife (named Grace) of the atrocity he has committed (the murder of a fellow soldier, a fratricide that recalls Platoon’s “We did not fight the enemy, we fought ourselves”) and the film shows Grace and Cahill’s family pulling together to help heal the wounds the war has inflicted. Read alongside one another, The Hurt Locker’s limited and prejudicial point of view, moral heroism and decontextualized PTSD presents us with a positive formulation of the war, while Brothers enfolds the returning traumatized combat veteran in discourses of healing and redemption.

So what of Bacevich’s claim of an all-pervasive New American Militarism shaping US popular culture and underwriting the waging of war in the early twenty-first century? Within the set of bounded possibilities available to filmmakers working in Hollywood, and at a time when US troops are still being killed on the battlefield, a cycle of war movies has been made that could be said to be largely critical of war. Filmmakers have been willing to face up to difficult, irreconcilable facts: that US troops have committed atrocity, that the wars have not been a success, and may even have been counter-productive, that political leaders and jingoistic constructions of national identity can be harmful, and so on. As Douglas Kellner puts it, “…the cycle testifie[s] to disillusionment with Iraq policy and help[s] compensate for mainstream corporate media neglect of the consequences of war” (222). However, many of these films remain largely unseen in the US and, as we have seen, by far and away the most successful film in the cycle, The Hurt Locker, offers a positive, revisionist view of the war, a view that if extended across cultural production is likely to seed further war in the future.

References

Allen, Nick. “Hurt Locker Producers Sue 5,000 Over Digital Piracy”. The Daily Telegraph. 30 May 2010. Print.

Alpert, Robert. “Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker: A Jack-in-the-Box Story.” Jump Cut 52 (2010). Print.

Bacevich, Andrew J. The New American Militarism: How Americans Are Seduced by War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005. Print.

Boggs, Carl, and Tom Pollard. The Hollywood War Machine: US Militarism and Popular Culture. Boulder, Colo.: Paradigm, 2007. Print.

Carruthers, Susan. “No One’s Looking: The Disappearing Audience for War.” Media, War & Conflict 1 1 (2008): 70-76. Print.

Clover, Joshua. “Allegory Bomb.” Film Quarterly 63 2 (2009): 8-9. Print.

Denby, David. “Anxiety Tests: The Hurt Locker and Food, Inc.” New Yorker 29.06.09 2009: 84. Print.

Faludi, Susan. The Terror Dream: What 9/11 Revealed About America. Atlantic Books, 2007. Print.

Hedges, Chris. War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning. New York: Public Affairs, 2002. Print.

Kellner, Douglas. Cinema Wars: Hollywood Film and Politics in the Bush-Cheney Era. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. Print.

Macaulay, Scott. “Interview: Barry Ackroyd and Kathryn Bigelow.” Filmmaker 17 3 (2009): 32-38. Print.

Schatz, Thomas. “Old War/New War: Band of Brothers and the Revival of the WWII War Film.” Film and History 32 1 (2002): 74-77. Print.

Scott, A.O. “Apolitics and the War Film.” New York Times 7th Feb 2010. Print.

Sklar, R. “The Hurt Locker.” Cineaste 35 1 (2009): 55-56. Print.

Sturken, Marita. Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the Aids Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1997. Print.

Taubin, Amy. “Hard Wired.” Film Comment 45 3 (2009): 30-32, 34-35. Print.

Žižek, Slavoj. “Green Berets With a Human Face.” LRB blog, 23 Mar 2010. Web. 31.05.2011.

Written by Guy Westwell, 2011; edited by Nick Jones, 2011, Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2011 Guy Westwell/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post