Plot East Prussia, 1942. Twenty-two-year-old Traudl Junge is interviewed to be Adolf Hitler’s personal secretary. Her dictation is awful but Hitler chooses her as she is from Munich, young and pretty. Berlin, 20 April 1945. Traudl wakes up in the bunker below the Reichskanzlei to the boom of approaching Soviet artillery fire. It is Hitler’s birthday and the Red Army is within 12 kilometres of the city centre. Albert Speer encourages Hitler to stay in Berlin, but other top Nazis turn to Eva Braun to persuade Hitler to leave. Above ground, the Hitler Youth – including 13-year-old Peter – are fighting on and idealistic SS doctor Schenck wanders amid official detritus, ignoring Himmler’s orders to attend a makeshift field hospital outside Berlin. Eva Braun holds a dance to celebrate Hitler’s birthday, which is interrupted by an artillery shell. Hitler emerges from the bunker to give medals to Peter and the children. General Mohnke, who has ordered the western displacement of Hitler’s troops, arrives at the bunker expecting to be shot but is charged with defending Berlin. Hitler is forced to admit the war is over. Traudl decides to stay. Hitler rants about Goering’s attempts to take charge and gives Traudl and the other women suicide pills. Traudl types up Hitler’s and then Goebbels’ last wills. Speer begs Hitler to surrender, admitting he has been ignoring his orders for months. Hitler and Eva Braun are married in the bunker and Hitler orders his body to be burnt before the Russians arrive. The final days of the Third Reich pass with the guards staying drunk. 30 April 1945. Hitler helps to put down his dog and takes advice on how to kill himself. He shoots himself and Eva while taking the suicide pills, and his body is burnt. Magda Goebbels murders her six children in their drugged sleep and her husband shoots her and himself, their bodies too being burnt. Traudl makes it through the Russian lines with young Peter to safety (Falcon).

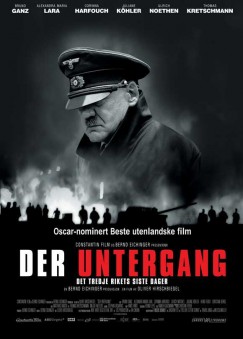

Film note Based on German historian Joachim Fest’s book Der Untergang–Hitler und das Ende des dritten Reiches/Inside Hitler’s Bunker–The Last Days of the Third Reich (2002) and the critically acclaimed documentary Im Totem Winkel–Hitler’s Sekretärin/Blind Spot–Hitler’s Secretary (André Heller and Othmar Schmiderer, 2002), Downfall plays with “the voyeuristically enticing prospect of observing the last [twelve] days of [the Third Reich’s] existence” (Haase 2006: 191). The film grossed $39m at the German box office, and $58.2m worldwide, including $5.5m in the US. Positive reviews, a Bambi Award and an Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Film helped boost ticket sales. Many critics praised the stage-quality acting (particularly by Bruno Ganz who was awarded the Bavarian Film Award for Best Actor in 2005), the film’s realist style, its historical verisimilitude and its Hollywood-style dramatic tension. Yet, the film also attracted criticism, with a number of commentators raising moral, ethical and political questions about the use of the conventions of entertainment cinema to represent the Nazi past.

History on film Downfall can be usefully placed within the longstanding and ongoing debate concerning the role that German cinema has played in attempting to acknowledge and examine the nation’s traumatic past. As Reimer and Reimer note, “The German term for coming to terms with the past through film, Vergangenheitsbewältigungsfilm, implies that film can be used as a means for reflection on and judgment and internalization of the past” (2). Beginning this tradition only one year after World War II, Trümmerfilme (‘rubble films’) such as Die Mörder Sind Unter Uns/The Murderers Are Amongst Us (Wolfgang Staudte, 1946) dealt with questions of guilt and atonement and sought “to come to grips with the recent past against the still contemporary background of ruined cities” (Kaes 12). From the 1950s, once economic conditions started to improve (at least in West Germany), an increasing number of films reflected the population’s general desire to put “the past […] at rest” (Kaes 17). Costume epics, comedies and melodramas replaced the Trümmerfilme and the popularity of the Heimatfilm and a cycle of nostalgic war films indicated how West Germany cultivated a form of collective amnesia and attempted to regain national pride by “turning the Federal Republic into a new (idyllic) homeland” (Hake 118). It was not until the late 1970s that filmmakers once again broached the subject of wartime atrocities. A denunciation of the state’s willful amnesia was at the core of the collective film Deutschland im Herbst/Germany in Autumn (Alexander Kluge et al, 1978). This film, made by nine directors of the New German Cinema, aimed at recreating the effects of memory–as a momentary impression–by means of experimental montage and juxtaposition of historical, fictional and non-fictional images. Similarly, Die Blechtrommel/The Tin Drum (Volker Schlöndorff, 1979) explored the difficulties of growing up within and identifying with a country capable of the Holocaust, while Die bleierne Zeit/Marianne and Juliane (Margarethe von Trotta, 1981) depicted the rebellion of those born after the war against their parents through the dramatization of the life of terrorist Gudrun Ensslin. Downfall shares with this 1970s cycle a desire to return to World War II. However, unlike the New German Cinema, the contemporary cinema is driven first and foremost by a commercial imperative and Downfall leavens its account of Hitler’s last days with a melodramatic narrative focused on interpersonal relationships. In this respect, the film has much in common with another key film of the 1970s, the US television series Holocaust (NBC, 1978) which when broadcast in West Germany was watched by over 20 million people (50% or the adult population) (Kaes 30). Like Downfall, Holocaust combined public history–enhanced by sparse intercutting of authentic film footage–with fictional, dramatized private stories. Another significant precursor is Das Boot/The Boat (Wolfgang Petersen, 1981) which, according to Sabine Hake, is indicative of the “continuous compromise between art cinema and popular {film]” that has shaped German cinema since the 1980s (Hake 3). Indeed, Petersen’s film managed to “make [the] serious topics [of war] accessible to mass audiences by means of popular genre cinema” (Haase 2007: 77). Das Boot appealed to national and international viewers as it touched universal issues and the experience of global war, yet it did so by making spectators engage and identify with a “group of unfortunate [Nazi] innocents under pressure” (Haase 2007: 77). This mixing of familiar and unfamiliar themes as well as the unusual–national and international–alignments that the film offers to its audience is precisely what links Petersen’s film to Downfall. Indeed, Downfall, in line with the global ambitions of its production company, Constantin Film–responsible for international blockbusters such as Resident Evil (Paul W. S. Anderson, 2002)–is primarily aimed at a mass audience and does so especially by means of exploiting the “affective” power of classical Hollywood style and convention (Moltke 21).

This concern about the depiction of traumatic historical events with the codes and conventions of entertainment cinema is inherently linked to a wider debate about film and history. As we have seen, many filmmakers have attempted to come to terms with the Nazi past and the dispute between different approaches has often concerned the modes of representation. The filmmakers of the New German Cinema often opted for a Brechtian approach utilizing confrontational aesthetics which ignite in viewers a reflexive and critical detachment; others have favored a realist style combined with entertainment cinema conventions that encourage the audience to engage emotionally yet remain passive. Following this latter trend, Downfall has been praised by many–not least producer Bernd Eichinger, director Hirschbiegel, and the Hitler biographer Ian Kershaw–for its accessibility, authenticity and political neutrality. Others, such as David Denby, have found the film’s commercial style “morally and imaginatively questionable, [as it results in] a compromise with the unspeakable that borders on complicity with it”.

Unreliable testimony This issue comes in to stark relief around the use of the testimony of Trudl Junge. Downfall’s narrative linearity, its use of continuity editing and historical verisimilitude serve to offer the old woman’s testimony as one of ‘truth’. In contrast, the documentary Im Totem Winkel–Hitler Secretärin uses crosscutting between Junge and a number of other interviewees, in order to indicate the unreliability of her testimony. Im Totem Winkel also uses fade outs to indicate the questionable nature of Junge’s perspective; black inserts are used, for example, to allow viewers to reflect on the revelation that Hitler had an aversion to speaking ill of Jewish people. To this extent, the comparison between Downfall–which only once makes mention of the Holocaust–and the documentary which influenced the film also reveal how Downfall fails to acknowledge the essential “blindness that accompanies […any sort of] individual memory” (Davidson 71).

The film, from the beginning, invites us to align with Junge by introducing the narrative with an extract from Im Totem Winkel followed by a close-up of Junge illuminated only by torchlight. Further shots reveal her anxiety but also excitement at her imminent meeting with Hitler. This meeting is carefully constructed following the classical rules of suspense: an officer opens the Führer’s door and invites him to greet the girls; we still have not seen Hitler but we know he is going to make his entrance, we hear his slow steps offscreen, one more shot of the potential secretaries leaning toward the door parallels our heightened curiosity, then finally the Führer appears, shot from a low camera angle that symbolically conveys his “celebrity status” (Krimmer 97). The following scene, rather than keeping Hitler in a position of superiority, puts him on the same level as Junge. A series of shot-reverse-shots give each character equal status and create a filmic “proximity […] and intimacy” between the two (Moltke 35). As a consequence, the spectator–who is already aligned with Junge–has access to the emotional–and possibly sexual–tension that links the young girl to the Führer. Here, Downfall’s “deliberately staged dramaturgy of intimacy” (Moltke 35) functionally assists the film’s attempt to explore the relationship between Hitler and ‘das Volk’, a relationship based on a notional equality and on “Hitler’s much vaunted sex appeal” (Krimmer 94).

Likewise, the viewer is invited to participate in the emotive stress of the Nazi female bystanders in a later scene. Hitler is depicted announcing the impending defeat; although he invites the women to leave, they refuse to do so, following the example of Eva Braun whose loyalty is rewarded by Hitler with a passionate kiss. The melodramatic mode of representation here is accomplished by means of placing the camera in the middle of the group and alternating slight camera movements–showing medium shots of the worried expressions of Hitler’s followers–with close-ups of Junge’s shocked face. This alternation makes us believe that the Junge’s look stands for the crowd surrounding her, and that through her reactions we can grasp those of the others. Yet, what is compelling about this composition is that it occurs at a time when Junge is depicted as hypnotized by Hitler’s sexual power. Indeed, the erotic appeal of Hitler and Eva Braun’s kiss seems to be the reason for Junge’s decision to stay. Here the film suggests sexual attraction is a form of hypnotizing power one that seems to refer to what Denis de Rougemont has defined as Hitler’s ability to seduce the unconscious of the individual as well as that of the masses by means of “depriving them of their means of reflection” (73). To this extent, the scene skillfully manages to explore one of the most controversial aspects of the relationship between fascism and its followers – that is fascism’s ability to “sexualiz[e…] collectivism” (Rougemont 79).

Fascism’s collapsing of the erotic and the political is also explored in the Italian film Vincere (Marco Bellocchio, 2009) which in one sequence crosscuts between a scene of brutal sexual intercourse–between the young Mussolini and his secret mistress–and extracts from a historical documentary showing the Duce making a powerful speech to the masses. In making this juxtaposition, Bellocchio chooses to portray fascism as a dictatorial power that understood “leadership as sexual mastery of the ‘feminine’ masses” (Sontag 132). Both Downfall and Vincere–even if in very different ways–question the insistent commitment of fascism’s followers to their idols even after their leaders, respectively, die or repudiate them. Indeed, Downfall’s film score (composed by Stephan Zacharias) contributes to this: the film insistently plays Zacharias’s reworking of ‘Dido’s Song’ from Henry Purcell’s opera Dido and Aeneas. The song is “thematically… concerned with [Dido’s feared] death from a broken heart over her husband’s leaving” (Bathrick 15). In using this song, Downfall conveys a sense of emotional and personal loss, one that stems from the understanding that the man who seduced his subjects with the promise of both a “magnificent experience […] forbidden to ordinary people” (Sontag 132) and the appealing “prospect of being freed from a guilty conscience” (Rougemont 74). Here the film’s formal construction provides “emotional cue[s] for engaging with the narrative” (Moltke 33). Certainly, in the case of a mainstream film about Hitler, the use of this kind of emotional, melodramatic technique is extremely controversial in that there is always the risk of “bath[ing] the atrocities of historical perpetrators in the revisionist light of compassion” (Moltke 42).

Cinema of consensus Downfall can be said to belong to what Erich Rentschler has described as a post-wall cinema of consensus (274). Contemporary directors tackle controversial events but do so using various methods that seek to unify their audience, a feature of German culture since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Downfall is a form of heritage film, which according to Lutz Koepnick is “a mode of filmmaking […] typifie[d by…] the production of usable and consumable pasts, of history as a site of comfort and orientation” (51). The move towards consensus is made possible in Downfall–as in other heritage films–by means of construction of a unified tone that plays with the viewers perception of public history as a collective element experienced equally by everyone. The film relies heavily on the evocative power of visual references such as swastikas, Nazi uniforms and fascist architectures as well as on the emblem of Hitler’s bunker and the Führer’s image. In doing so the film turns public history into a site of familiar symbolic elements and makes it a consumable spectacle that can “be explored, experienced, and enjoyed without guilt” (Hake 213).

Downfall continuously shifts its gaze between outside and inside, between the military situation of the crumbling city and the private stories of those inside Hitler’s bunker. In the bunker “Mr. Ganz’s Hitler is obviously the central figure, [yet] he is [also] frequently offstage” and nearly never shown alone (Scott). This underlines what Eva Braun clearly states in the film–that it is impossible to really know Hitler. Indeed, instead of attempting to decode the enigma of Hitler, the film focuses on Hitler’s followers: some are cowards, some are confused and some are even portrayed as brave; however, “the mechanisms of character identification” (Bathrick 12) urge us, according to each personal story, to empathize with most of them. Indeed, the more Hitler (and Goebbels) brutally rage against the entire German people, “the more we sympathize with the hapless bystanders… and the more convincing they seem–despite their various pasts–as victims” (Bathrick 13). Thus, the film invites us to look at war criminals like Speer, Schenck and Mohnke as Hitler’s opponents; indeed, this contrast is conveyed through both the narrative and mise-en-scène such as the table and desks that very often separate Hitler from those who oppose him. In so doing the film offers “oversimplified portraits of German as victims […] run[ning] the risk of leveling differences between different kinds of victims” (Krimmer 82).

This narrative focus on personal drama and victimhood, which is shared by a number of other contemporary German heritage films, is used to address questions of individual culpability. Films such as Sophie Scholl–Die Letzten Tage/ Sophie Scholl–The Final Days (Marc Rothemund, 2005) and NaPolA/Before the Fall (Dennis Gansel, 2004)–the latter co-produced by Constantin Film–use the conventions of mainstream melodrama to explore the effect of the Nazi regime on the lives of young and naïve Germans. These quite different films share a manifest desire to depict their protagonists as fundamentally not responsible for the horrors of the Third Reich. Similarly, Downfall does not show the horrors of Nazi crimes and the Holocaust; and, in the penultimate scene of the film, the portrayal of the distraught Traudl Junge and the orphan Peter Kranz in the middle of ruined Berlin implicitly aligns the sufferings caused by fascism on its naïve followers to those of the whole nation.

In sum, Downfall shows history through the lens of a post-Berlin Wall heritage cinema that seeks to absolve ordinary Germans of culpability in the Nazi past. The film is “easy to digest […due to] its consensus oriented perspective” (Koepnick 78). Yet, if the film has a saving grace, it is in the activation of empathy towards Hitler’s followers and the activation of strong emotions that may be helpful in increasing awareness of how individuals inhabited historical events in complex and contradictory ways. According to Alison Landsberg, this is the potential power of cinema’s “prosthetic memory” (26). At a time when the witnesses of the Holocaust and the Nazi past are beginning to pass away, “organic memory… has become precarious, [thus] German cinema now turns it into a primary site of transmitting memory between generations” (Koepnick 57). Indeed, it is a new generation with no direct memory of the war that Downfall addresses. In the film‘s closing scene, Junge’s final exploration of her personal guilt serves as a call for reflection on the meaning and effects of mediated, “celluloid memory” (Koepnick 76). This final scene reflects on the dangers that lie underneath young people’s unconditional trust in popular figures and media product; indeed, by showing Junge’s reflections on her inexcusable fascination with Hitler, Hirschbiegel requires us–and especially a younger generation–to think about the similar fascination experienced in watching the film. Thus, Downfall finally–and unfortunately only at the very end–acknowledges the limits of film history and asks us to remember that the cinema can be an instructive form of historical writing only as long as “the contingent and ruptured nature of […] history” (Koepnick 82) is recognized.

References

Bathrick, David. “Whose Hi/story Is It?: The US Reception of Downfall”. New German Critique. 34.3 (2007): 1-16. Print.

Davidson, John E. “Shades of Grey: Coming to Terms with German Film Since Unification” German Cinema Since Unification. Ed. D. Clarke. London: Continuum, 2006. Print.

Denby, David. “Back in the Bunker: Downfall”. Newyorker.com. 14 Feb. 2005. Web. 11 Jan 2011.

Falcon, Richard. “Review: Downfall” Sight and Sound. May 2005. Web. 11 Jan 2011. Web.

Fest, Joachim, Der Untergang–Hitler und das Ende des dritten Reiches/Inside Hitler’s Bunker–The Last Days of the Third Reich. London: Macmillan, 2002. Print.

Haase, Christine. “Ready For His Close-Up?: Representing Hitler in Der Untergang.” Studies in European Cinema. 3.3 (2006): 189-99. Print.

—. When Heimat Meets Hollywood: German Filmmakers and America 1985-2005. Rochester, New York: Camden House, 2007. Print.

Hake, Sabine. German National Cinema. London: Routledge, 2008. Print.

Kaes, Anton. From Hitler to Heimat: The Return of History as Film. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989. Print.

Koepnick, Lutz “Reframing the Past: Heritage Cinema and Holocaust in the 1990s”. New German Critique. 87 (2002): 47-82. Print.

Krimmer, Elisabeth. “More War Stories: Stalingrad and Downfall’. The Collapse of the Conventional: German Film and its Politics at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. Eds. J. Fisher and B. Prager. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010. 81-109. Print.

Landsberg, Alison. Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004. Print.

Moltke, Johannes von. “Sympathy for the Devil: Cinema, History, and the Politics of Emotion.” New German Critique. 34.3 (2007): 17-43. Print.

Reimer, Robert C. and Reimer, Carol J.. Nazi-retro Film: How German Narrative Cinema Remembers the Past. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1992. Print.

Rentschler, Eric. “From New German Cinema to the Post-Wall Cinema of Consensus”. Cinema and Nation. Eds. M. Hjort and S. MacKenzie. London: Routledge, 2000. 260-77. Print.

Rougemont, Denis de. “Passion and the Origin of Hitlerism”. The Review of Politics. 3.1 (1941): 65-82. Print.

Scott, A.O. “The Last Days of Hitler: Raving and Ravioli”. New York Times.com. 18 Feb. 2005, Web. 09 Jan. 2010.

Garrett, Diane. “Homevideo Biz Takes a Hit in ’08.” Variety.com. 5 Jan. 2009. Web. 11 Nov. 2010.

Sontag, Susan Under the Sign of Saturn. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1980. Print.

Written by Caterina Lotti (2010); edited by Guy Westwell (2011), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2011 Caterina Lotti/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post