Plot Connecticut, mid-1950s. Expecting their first child, Frank and April Wheeler buy a house in a suburban development. Some years later, Frank and April have had two children and their marriage is under strain. Frank is unhappy in his job in the marketing department of a New York firm. On the night that April (an aspiring actress prior to meeting Frank) performs in a production for a local theatre group, the couple argue. The next day, Frank has drunken sex with his secretary, returning home late to a party organized by April for his 30th birthday. April suggests they move to Paris, since it is the only place worth living according to what Frank told her when they first met; she will support the family while he uses the time to discover what he wants to do with his life. Frank agrees. For a few months, their lives are completely changed by these future plans. When Frank’s boss offers him a promotion his enthusiasm for moving to Paris cools; soon after, April announces that she’s pregnant, and he becomes even less sure about their plans. A neighbour, Mrs. Givings, brings her mentally unstable son John to the Wheeler’s home to show him how happy a normal suburban life can be. After finding out that Frank is considering the promotion, April argues with Frank, and Frank discovers that April is considering an abortion. The fight ends with Frank making the decision that he will take the job and April will have the baby. They go on a night out with their neighbours Shep and Milly. After Frank takes a drunk Milly home, April has sex with Shep. Frank tells April about his affair with Maureen, which he has ended, which leads April to realize that she doesn’t love him anymore. During a dinner, John provokes Frank, who becomes enraged. The fight between Frank and April escalates further. She tells Frank that she hates him. The next day, while Frank is at work, April miscarries while performing an abortion and bleeds to death.

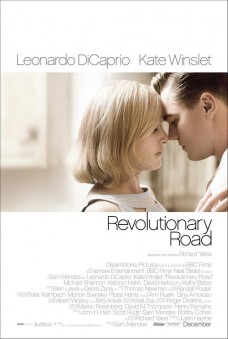

Film note The rights for Revolutionary Road were originally optioned by Evamere Entertainment and the BBC, these companies joined for the production by Dreamworks SKG, Neil Street Productions and director Sam Mendes’ own production company. The film was made on a relatively small budget of $35m and grossed $5.2m on its opening weekend in January 2009, going on to secure $75.2m worldwide. The small budget of the film made it an unusual choice for star Leonardo DiCaprio, an actor more commonly recognized for his involvement in large-scale blockbusters like Gangs of New York (2002), Blood Diamond (2006) and Body of Lies (2008). Compared to DiCaprio, co-star Kate Winslet has taken part in more independent projects, such as Hideous Kinky (1998) and Romance and Cigarettes (2005). The casting of two actors best known for their collaboration in the romantic period drama Titanic (1997) added an interesting dimension to the on-screen relationship in Revolutionary Road: Titanic consists of a melodramatic narrative of heroism and survival, which contrasts with Revolutionary Road’s portrayal of a relationship falling apart. The juxtaposition indicates both actors current commitment to risky independent projects and their maturity in realizing difficult and challenging roles. Revolutionary Road was nominated for three Academy Awards and four Golden Globes. Indeed, the 2009 Oscars seemed intent on proving that there is still a strong place for character-based films that addressed political issues, with The Reader (2008), Milk (2008), and Frost/Nixon (2008), nominated alongside Revolutionary Road for Best Picture.

Adaptation and interiority Revolutionary Road is based on the 1961 novel of the same name by Richard Yates. The novel is set in 1955, and provides a trenchant critique on the American cultural trends of the 1950s. The film adaptation, made fifty years later, has far more critical distance from the time depicted. Yates’ account of a middle-class family living in the suburbs is carefully constructed and meticulously detailed. Through a concentration on the internal lives of the characters (not just protagonists Frank and April Wheeler) and their conflict with the external world, the novel analyses the unsaid and unseen in popular suburban culture and society of the 1950s. The most revealing thoughts and feelings are communicated through Yates’ description of the character’s internal lives: their thoughts, hopes and fears. This mode of storytelling, which makes the novel so enjoyable to read, proved to be a challenge for screenwriter, Justin Haythe. As in most literary adaptation, details and events had to be cut to allow the novel’s narrative to fit the conventional time frame of a feature-length film. As a result, the film omits some significant dialogue, shortening important scenes to such an extent, it could be argued, that they lose their urgency and original meaning.

The first instance of this is when April announces her idea of moving to Paris. In the film, the scene is very short compared to the novel and therefore creates the impression that April is more decisive. In the novel when Frank calls her idea ‘sweet’, April replies: ‘For God’s sake, Frank, I’m not being ‘sweet’’ (Yates 109-110), an interaction which, along with April’s subsequent interior monologue, reveals her insecurities, guilt and feelings about their relationship; she feels trapped by miscommunication and suburban living. By contrast, in the film adaptation the characters are romanticized and their actions are more determined. As Lawrenson notes, “Winslet’s idea to move to Europe has the conviction of a viable plan” rather than the dream-like quality of the novel (71).

In the novel, April’s personal insecurity becomes very clear in the conversation with Shep after they have had sex in the car. She ends the interaction by saying “…you see I don’t know who I am …” (Yates 262). At this point, the tragedy of her unhappiness with her life is communicated succinctly to the reader, creating an emotional understanding which is completely missing in the film. Instead, the scene ends with Shep confessing his love for April and her rejecting him. The alterations made to this exchange of dialogue in the film change the meaning of the liaison, creating a negative portrayal of April. The adapted scene fails to communicate April’s feelings of being identity-less which cause her to engage in a meaningless act of adultery.

During the period of the novel when April is pregnant and Frank attempts to talk her out of an abortion they have endless conversations that are missing in the film. One is about “morality” and “convention” and April claims, to Frank’s anger, that she doesn’t know the difference. As the conversation continues they touch on April’s past with her parents who have neglected her, resulting in long-term emotional harm. The film barely mentions April’s past and this makes her character flat and more difficult for the audience to identify with. In the novel, before she performs the deadly abortion on herself, a flashback describes April’s parent-less childhood. The sequence is heartbreaking to read. Placing that flashback moments before she carries out the abortion is significant, since it creates a connection between the past and present, which the film neglects. The effect of this is that the film creates the impression that April’s decision to abort is a part of her personal crisis, rather than a result of childhood trauma.

It is a challenging task to turn a novel that is so heavily based on “events that are interior, unseen and unspoken” into a successful film (Lawrenson 71). As Lawrenson points out: “[In the novel the] dialogue is sharp, often brutal, and always naturalistic. Much of the drama emerges from the tension between the public face that the Wheelers put on, and the conclusive disappointments and curdling resentment of their private thoughts. It’s not material that is easily adapted for the screen” (71). Although exact thoughts are not known, the film uses revealing close-ups and moments of contemplative silence in an attempt to communicate the inner monologues of the characters.

The story is about having the courage to live the life you want and deserve, even if this means rebelling against convention and resisting cultural expectation. In the film the tragedy of April and Frank’s situation lies in Frank’s inability to summon the courage to leave his job and escape. His relief when April’s plans are dashed by pregnancy are clearly visible. In the novel, however, it is the differences between Frank and April’s personalities and their inability to communicate which makes them unable to put their plans into action. This tragedy is lost in the film in favour of the clear-cut reasoning of an unexpected pregnancy, a topic that is easier to communicate to an audience without the need for the viewer to be privy to the characters’ thoughts. Had they embraced the mood and message of the novel farther “it might have been more than just almost a halfway decent movie adapted from a great novel” (Lawrenson 2009: 71).

Yates’ novel is considered an important left-liberal critique of the patriarchal conservatism of the 1950s and the destructive “hopeless emptiness” of the American Dream. The novel is celebrated because Yates was ahead of his time in portraying the repression and societal pressures of this crucial decade. Although Mendes is not a mainstream director and has a history of choosing to work on social dramas (American Beauty (2001)), the film never quite captures the dark, hopeless tone of the novel and as a result its politics are not as distinct as those of Yates. The film neglects the wider historical context and greater historical distance appears to have led to an emphasis being placed on the universality of the story. This results in a loss of understanding of the desperate mood of the post war years in which people like the Wheelers aspired to “so much more” but often were vulnerable to the effects of a harsh capitalist society. Mendes said of the film that, “We don’t fetishize the ‘50s. You learn about them almost by accident. It is not about the suburbs. It is about a couple. I always felt it was a universal story, and where they are is tangential to the story of their marriage” (Nick 19). It could be argued that the time of the release reveals Mendes’ desire for Revolutionary Road to be an Academy Award winning film, and therefore he may have been inclined to avoid risks in favour of attracting audiences. For example, the romantic classical score by Thomas Newman could be argued to soften the impact of the movie on the spectator by connecting the film with the recognizable and comfortable familiarities of classical Hollywood. The theme and variation style of composition that Newman uses could be argued to contrast with the tense social situations that take place throughout the film. By failing to communicate these frequent moments of awkward pressure the film distances itself from the self-reflective inner monologues of the novel.

Abortion and the American dream Abortion was not legalized in America until 1973; as such, Yates’s novel was groundbreaking in its inclusion of this issue. Indeed, abortion has always been a controversial issue in the US; as recently as 2009 the pro-life position polled at 51% of the population. The Wheelers represent an average family; they have one girl and one boy and live in a picture perfect house in the suburbs from where the husband commutes into the city for work while his wife maintains their home. This ideal of the nuclear family so central to America’s self-image is put at risk by April’s decision to get rid of her unborn child. However, the film shows the ideal to be anything but, with Frank committing adultery and unresolved tension and unfulfilled ambition, justifying April’s actions. The abortion is not discussed as having moral or religious implications, but is rather an action that April can take against the assumptions of society in order to drastically change their situation. Similarly, April’s suggestion that her and Frank swap gender roles would also have been highly unusual at the time; the film shows her suggestion confuses clearly defined gender relations and emasculates Frank. Clearly, April wants to achieve a shift in relations of power in order to gain happiness (Farrell 2). But the Campbells and the Givings see these “…new cultural values as a threat to the American way of life” (Farrell 2) creating pressure on Frank, to which he eventually succumbs.

Nostalgia for the patriarchal nuclear family, which is often based on the 1950s television sitcom model, is most commonly associated with a conservative political outlook (Farrell 3). In contrast, Revolutionary Road shows how this model of the family is false. The word family is associated with such ideas as “unconditional love, attachment, nurturance, and dependability” (Farrell 2). These are all terms that are primarily aligned with the female gender, and in particular the role of the mother. April’s character is depicted as displaying none of these characterizes and she struggles to mould herself to the role. Deep down she thinks of her children as accidents and doesn’t want to give birth to the one she carries. Towards the end of the film, Frank indirectly declares her crazy, because she prioritizes moving to Paris and leading a more independent life over family ideals. It is telling that the only person to understand the April is John Givings, the apparently insane son of Mrs Givings, who lives in a mental institution.

Marriage is also highly valued in American society. Betty Farrell argues that “…marriage is a necessity because it forms the nuclear family that will be the core of the social order” (94-95). This viewpoint is an important part of the context of Revolutionary Road, and is part of what April is shown to be fighting against. She rejects her marriage vows by ignoring the feelings of her husband and taking issues of life and death into her own hands. She ultimately ‘loses’ the fight, escaping not through life, but only in death. Despite April’s personal strength she cannot succeed in her struggle without the support of her husband. Without the aid of her husband she is unable to achieve the liberation she longs for, thus she is dependent even in her search for independence.

April’s desperate wish to move to Paris is a critique of the fact that the US does not necessarily deliver on its promise of freedom and equality for all. J. Emmett Winn writes that, “The United States is considered the land of opportunity despite one’s race, colour, creed, or national origin, an idea that is acknowledged in many parts of the world. Most Americans believe that the American Dream allows individuals to succeed without being burdened by unfair limitations” (1). The Wheelers are following the requirements of society in order to attempt to realize the American Dream, but they have been disappointed. Frank becomes absorbed (one might say co-opted) by the idea of the American Dream, and in doing so denies April her personal dream of moving to Europe. April’s sense of being trapped in a hopeless society (where men and women live according to societal pressures rather than their own happiness) is what ultimately leads to her death. Interestingly, this revisionist and critical view of the 1950s, which endorses abortion as a justifiable act, and in doing so provokes controversy, can also be found in other contemporary views of the 1950s and early 1960s, including the television series Mad Men (ABC).

The suburbs are another key aspect of the film; they are both the backdrop of the story and also an important symbol in American culture. Dolores Hayden writes that, “More Americans reside in suburban landscapes than in inner cities and rural areas combined… Suburbia is the site of promises, dreams, and fantasies. It is a landscape of the imagination where Americans situate ambitions for upward mobility and economic security, ideals about freedom and private property, and longings for social harmony and spiritual uplift” (Hayden 3). We can see here that the Suburbs are closely linked with the American Dream, as described by Winn. Hayden also links the development of female domesticity in the US with the beginning of suburban settlement (Hayden 6). She goes on to say that “for women especially, the single-family suburban house implies isolation, lacking physical and social context” (Hayden 7). This is what April struggles with and doesn’t want to conform to, since the price to pay, her individuality, is too high.

Revolutionary Road is American in its thematic tendencies, focusing on family, gender roles, success and the suburbs. What makes it stand out is the critical stand it takes towards these values by essentially being a liberal film about conservative traditions. Aesthetically it incorporates the iconic fifties look. The final shot of April, standing in front of the picture window, which represents everything she hates and has destroyed her, is iconic in its depiction of suburban life. The medium close-up of her face is framed by the small sections of the window, suggestive of the bars of a prison and entrapment. The last shot is simply the picture window and a bloodstain on the carpet: the supposedly wonderful American dream has killed her.

Revolutionary Road was released in the US just over a month after the election of Barack Obama. This shift in the balance of power from neo-conservativism to liberal-progressivism indicated a rejection of traditionalist beliefs in favour of more the open-minded acceptance that would allow an independent thinker like Rose to thrive. George Bush Jr.’s conservative family values (the advocacy of conventional gender roles, a strong anti-abortion position, and so on) clearly lost favour with an American majority who, like Frank and April, desired social freedom. Obama’s campaign slogan ‘Yes, we can’, and its popularity, could be argued to represent a generation who, like the protagonists of Revolutionary Road, want change. Frank and April Wheeler are determined to change their lives in a time when social expectations were conservative and unquestioned. Against this backdrop, Frank, unlike April, has a ‘No, we can’t,’ mentality, and it is likely that audiences at the time of release may not have viewed his character sympathetically as a result. April desires a different, equal, more expansive and adventurous life and we are shown how conservatism (reproduced in Frank in spite of his protestations) prevents her from reaching this goal. As such the film maintains a critical attitude that may well be more dilute that Yates’ acidic account but which still has something to say about how the 1950s continues to be an important touchstone for left and right wing politics in the twenty first century.

References

Farrell, Betty G. Family: The Making of an Idea, an Institution, and a Controversy in American Culture. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1999. Print.

Hayden, Dolores. Building Suburbia: Green Fields and Urban Growth, 1820-2000. New York: Pantheon Books, 2003. Print.

Lawrenson, Ed. “Review: Revolutionary Road.” Sight and Sound 19.2 (2009): 71. Print.

Powers, Stephen, Rothman, David J. and Rothman, Stanley. Hollywood’s America: Social and Political Themes in Motion Pictures. Oxford: Westview Press, 1996. Print.

Saad, Lydia. “More Americans ‘Pro-life’ than ‘Pro-choice’ for First Time”. Gallup.com. 15 May 2009. Web. 28th Feb 2011.

Winn, J. Emmett. The American Dream and Contemporary Hollywood Cinema. London: Continuum, 2007. Print.

Yates, Richard. Revolutionary Road. London: Vintage, 2007. Print.

Written by Hannah Patterson (2009); edited by Abigail Stroman (2011), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2011 Hannah Patterson/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post