Plot Los Angeles, Present Day. The film shows an extraordinary/ordinary twenty-four hours in the lives of a cross-section of Los Angeleanos. The main stories are of the immediate offspring of two elderly men dying of cancer, Earl Partridge and Jimmy Gator, the producer and presenter (respectively) of popular television show, ‘What Do Kids Know?’. Frank, Earl’s son, is the cult leader of ‘Seduce and Destroy’ a ‘men’s group’ whose aim is to ‘tame the cunt’ and ‘respect the cock’ and has broken all contact with his parents and his past. Jimmy’s daughter, Claudia, reveals to her mother, Rose, that she has been abused by her father. When the delirious Earl reveals a dying wish to his nurse, Phil Parma, to see his son once again the nurse attempts to track Frank down. Meanwhile, a visit by Frank to his daughter leads her to binge on cocaine and loud music; the neighbours complain and Officer Jim Kurring investigates. A number of other plot-lines interact with these main narrative threads: Earl’s trophy-wife Linda admits that she married him for money but realises that she has fallen in love with him as he lies on his deathbed; quiz kid Donny, the television show’s champion from 1968 pursues his unrequited love for barkeep Brad; Stanley, Donny’s contemporary equivalent, the current champion is bullied by his exploitative dad Rick, leading to Stanley’s on-air rebellion; the shadowy story of the murder of Marcie’s trick at the hands of her son, ‘the Worm’, as narrated to Jim Kurring by the boy rapper. A biblical rain of frogs (foreshadowed by the intermittent surreal weather reports which regulate the narrative into manageable sections) leads Frank to be reunited with Earl; Earl dies; the boy rapper saves Linda from her suicide attempt; Officer Jim aids Donny in returning the money he has stolen from Solomon Solomon; Rose elicits a confession from Jimmy then drives across town to be with her daughter; Jim, Donny and Rose’s cars and Linda’s ambulance all pass unknowingly at an intersection; Jimmy’s suicide attempt is foiled by a frog crashing through the skylight.

Film note Magnolia continues many formal, industrial and thematic trends developing within Hollywood through the 1990s. It demands to be seen primarily as an example of a semi-independent “author’s” cinema (it was written, produced and directed by 29-year old Paul Thomas Anderson) that developed in the wake of Steven Soderbergh’s and Quentin Tarantino’s successes. This new author’s cinema can be seen as something of a reliberalisation of Hollywood after the sensationalist infantilism of the Spielberg and Lucas blockbuster “Reaganite” era. Filmmakers such as Soderbergh, Ang Lee, Mike Figgis, David Fincher and others have been financed (during a period of economic growth under Clinton) by an increasingly confident globally incorporated Hollywood to make complex adult dramas showing a marked change in demographic address from blue-collar to white-collar America.

These films are decidedly more “literary”, “actorly” and “theatrical” than their Reaganite antecedents. The distinction between the independent American art-cinema (previously the province of independent filmmakers such as Hal Hartley, Tod Solendz, Jim Jarmusch, and John Sayles) and the mainstream is now far less distinct. Anderson’s budget for Magnolia was $37m accrued through New Line and Time Warner after the critical and box office success of his earlier film Boogie Nights (1997). This is a modest budget for a major Hollywood production but huge for a semi-independent film of its style and themes. Magnolia can be seen as a prime example of a cinema mediating the concerns of contemporary middle-class, middlebrow America: the ever increasing complexity and fragmentation of urban and suburban life; the emptiness of consumer and celebrity cultures; the crisis of authentic masculinity; and, as corrective to all of these, the search for personal growth and redemption through psychotherapeutic and New Age practices and principles.

Homage to Altman The film was largely well received, with many reviewers regarding it as the best film of 1999 and of greater value than American Beauty (1999), which won an Academy Award for Best Picture. It was Academy Award-nominated for Tom Cruise (Best Actor in a Supporting Role) for Aimee Mann (Best Song) and for Anderson (Best Screenplay). It also won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival in 2000. Much was made of Jon Brion’s score that drives the movie along in a similar way to Bernard Herrman’s music in Psycho, and of Aimee Mann’s specially commissioned songs. The main focus of critical attention has been Anderson himself and in particular his indebtedness to Robert Altman: Magnolia shares the episodic, multiple parallel storylines of Short Cuts (Altman’s 1997 film based on Raymond Carver’s short stories) as well as some of the cast used by Altman there and elsewhere (Julianne Moore, Henry Gibson). Anderson’s repeated use of the same group of actors–Julianne Moore, Philip Baker Hall, John C. Reilly, Alfred Molina and Philip Seymour Hoffman have all appeared previously in Anderson films–gives the film a marked sense of being an Altmanesque theatrical ensemble piece. His use of his native district of Los Angeles sets him and the film up as the “authentic” voice of middle-class LA, equivalent to Spike Lee’s Brooklyn or Martin Scorcese’s Italian Manhattan. Like Altman’s The Player (1992) the use of older generations of actors (Jason Robards) and the intermingling of different stratas of stardom (Tom Cruise) into an equalising collective “ensemble” presents Hollywood as a community of actors and presents this community as a group of professionals who have a special understanding about life, as ‘artists’. These actorly and theatrical emphases present the film as very much a “text to be read”.

The film is an example of a self-referential Hollywood proclaiming itself as the highest of art forms for documenting the contemporary. A significantly different industrial message to the “hey folks, its just entertainment!” of the Reaganite film. Andrew Britton notes that “Reaganite entertainment refers to itself in order to persuade us that it doesn’t refer outwards at all. It is purely and simply ‘entertainment’ […] and to present something as entertainment is to define it as a commodity to be consumed rather than as a text to be read” (3). Magnolia can be seen as a self-conscious turn away from the infantilized commercial aesthetic of much contemporary Hollywood fare that foregrounds special effects in the creation of sensational and fantastical events. Instead Magnolia deploys digital technology in an understated and low-key way. Offering the audience implausible camera angles within a plausible world thereby adding a gently “magical” element to an ostensibly “realist” and socially engaged cinema. Films such as The Ice Storm (1997), The Thin Red Line (1998), American Beauty and Fight Club (2000) all intersperse their traditionally realist narratives with surreal or metaphysical meditations and pauses, often achieved through the “magic” of the digital image.

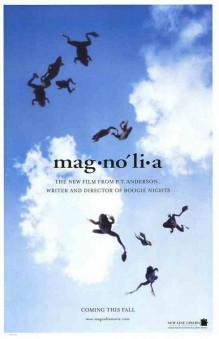

The Aquarian Conspiracy The individual protagonists of Magnolia’s multiple stories are presented as alienated and lonely, cut off from consciousness of the patterned network governing their lives (a network that slowly becomes visible to the viewer as the movie unfolds). This patterned network is figured as an organic unity; figuratively each story or character is revealed to be a separate petal of a single magnolia flower (an image used for the film’s poster). Each story follows a therapeutic pattern of alienation, confession and facing the past, catharsis, redemption and healing. The journalist Gwenovier forces Frank to face his past and he visits his dying father, allowing him to express his true feelings of love, anger, hurt and vulnerability. Claudia’s abuse finally comes to light through her mother Rose’s extraction of a reluctant confession from Jimmy, following which Rose is reunited with her daughter. Officer Jim has a constant confessional monologue with God whilst he drives his patrol car; the answer to his prayers comes in the form of Claudia, the chance to help her and the chance to help Donny. Donny confesses his crime and his love for Brad to Officer Jim who absolves him and helps him return the stolen money. Linda confesses her guilt about marrying Earl for money to the family lawyer. Divine intervention into various lives comes in the form of Phil, the angelic nurse who helps Earl and Frank; Gwenovier, a reporter who acts as a therapist to Frank; and the boy rapper who helps Officer Jim and saves Linda from suicide; as well as the rain of frogs which provides symbolic absolution for all and prevents Jimmy’s suicide. Ultimately it can be argued that the therapeutic work of the film extends to the viewer and the collective cathartic experience of the therapeutically informed audience. The film provides several adages from which its concerns proceed and which summarize its narrative, “strange things happen all the time” from the opening narration, “the sins of the fathers are visited on the sons” from Donny in the bar-room scene, “and the book says we may be through with the past but the past ain’t through with us” from Jimmy Gator during the record breaking edition of What Do Kids Know? and the collectively sung Aimee Mann chorus “It’s not going to stop ‘til you wise up” which presents a pop-song lyric expression of the film’s New Age goal of social transcendence through self-realisation.

These formal and narrative tendencies are indicative of the wider cultural influences of therapy and the New Age. In 1979 Christopher Lasch observed a “growing despair of changing society, even of understanding it, which underlies the cult of expanded consciousness, health and personal ‘growth’ so prevalent today” (4). Lasch also suggested that although “harmless in themselves, these pursuits, elevated to a program and wrapped in the rhetoric of authenticity and awareness, signify a retreat from politics and a repudiation of the recent past” (6). He concluded that “[t]he contemporary climate is therapeutic, not religious. People today hunger not for personal salvation, let alone for the restoration of an earlier golden age, but for the feeling, the momentary illusion, of personal wellbeing, health and psychic security” (7). Here, Lasch is describing a postmodern rejection of rationalism, of collective political intervention and of empirical cause and effect. In its place is an embrace of irrational belief systems: cults, mysticism, ‘spirituality’, magic and fundamentalist traditional religions and, centrally, the pursuit of personal growth through therapeutic practice. These include traditional Freudianism, Carl Rogers’ humanistic client-centered therapy and contemporarily holistic New Age therapies. These practices and their underlying principles have become a dominant cultural force throughout the 1980s and 1990s and have been absorbed by the mainstream and are manifest in all avenues of capitalist culture, business, society and the arts; not least Hollywood cinema.

New Age celebrants of this “new consciousness” such as Nevill Drury have described it thus: “Advocates of both the Human Potential Movement and the New Age emphasize the importance of… self-transformation which takes us beyond self itself. It is a journey towards wholeness, towards totality of being” (13). Likewise, Marylin Ferguson in her seminal New Age text The Aquarian Conspiracy states: “Just as personal transformation empowers the individual by revealing an inner authority, social transformation follows a chain reaction of personal change… ‘The new person creates the new collectivity’” (190-191). Underlying these statements, and the practices of New Age therapies, is a belief in holism: that all things are related in a universal organic and dynamic whole. Only through the individual realization of this universal relation will enlightenment be achieved. Whatsmore, this “personal growth” will lead to social transcendence and a kind of passive revolution whereby a society comprised of enlightened individuals will resolve all inequity. Magnolia inhabits this discourse, picking up on its central tenets and using holistic new age discourse to give structure to the many (similar) narrative arcs of its many characters.

Therapy films As already noted, the rain of frogs in Magnolia functions to signal a connected, holistic universe. Similar moments can be found in other ‘therapy films’, including the bag in the wind video in American Beauty, the reflections on nature in The Thin Red Line, and the storm itself in The Ice Storm. In these pivotal sequences verisimilitude is interrupted by moments of serendipitous coincidence, often made perceptible through the crosscutting of multiple parallel storylines and the deployment of special effects. These moments serve a “holistic” and transcendental impulse to show the relation of all parts to the perfect organic whole. Although these films have been claimed to signal a “reliberalisation” of Hollywood, they are in fact driven by a wholesale repudiation of politics. Indeed, the liberal therapy culture that Magnolia seems to promote should be viewed against actual economic, demographic and political changes in the workplace and markets of America in the 1990s.

Thomas Frank has argued that these kinds of values resulted in what he calls “market populism”, the idea widely held during the 1990s that entrepreneurs were the new liberators and democratisers of society. The success of this strategy, Frank claims, prevented all but small-scale political protest during a decade when wealth was redistributed from poor to rich on an unprecedented scale, when the notion of job security was considered a deterrent to self-realisation and individualism. As such, the liberating forces of the market and the ideology of new age therapies were conveniently aligned. The purportedly liberal aims of ‘personal growth’ easily co-opted by capitalist discourse of deregulation and entrepreneurial spirit. Frank writes: “Understood this way, the true warriors for workplace democracy weren’t trade unionists; they were the new breed of executives–the ones who abjured stuffy suits for casual wear, the zany ‘change agents’… white collar workers who demanded the right to drink beer and wear jeans in the office”. These were the guerrillas of a corporate culture that managed to persuade people that “by virtue of their attunement to [democratic] market forces [they were] bearers of a kind of soulfulness that government and union could never touch”. Frank argues that through this sophisticated conflation of discourses of self, individual freedom, and capitalist logic “management theory brought an unprecedented degree of workplace quiescence… in a decade when unemployment got as low as 4 per cent–making management extremely vulnerable to demands for increased wages–union organizing and strike activity remained at their lowest points since the 1920s’.

Whilst the therapeutic self-consciousness promulgated by Magnolia may be liberating in theory, it has to be considered against such a background as contributing to a populist myth, predicated on ‘style’ rather than substance, of market-led individual liberation which evidently contributes to collective political apathy and a lack of resistance in the face of overwhelming changes to individual workers rights. The therapy film requires its characters and its viewers to strive to improve their (troubled) social experience via individual reconstruction but crucially without recourse to the kind of collective political activity that might make this improvement possible. Since Magnolia’s release the liberal but morally compromised Democrat presidency of Bill Clinton has ended and he has been replaced by the hard-line, right-wing, ex-governor of Texas, George Bush Jr., and the indications are that the US economy is moving into recession. The recent success of Traffic (2000) might be read as the high-watermark of a cycle of movies that while seemingly liberal on the surface actually maintained the foundations required for the rebuilding of a right-wing political consensus. On the other hand, the difficulty in establishing support for this right wing shift (demonstrated by a national election that proved impossible to decide one way or the other) might prompt Hollywood to define itself against Bush’s political program (without losing its audience) and accentuate the liberal dimension of semi-independent movie production at the beginning of the 21st century.

References

Britton, Andrew. “Blissing Out: The Politics of Reaganite Entertainment”. Movie 31/32 (1986) 1-42. Print.

Drury, Nevill. The Elements of Human Potential. Shaftesbury: Element Books, 1989. Print.

Faludi, Susan. Backlash: The Undeclared War Against Women. London: Chatto and Windus, 1991. Print.

Faludi, Susan. Stiffed: The Betrayal of Modern Man. London: Vintage, 2000. Print.

Ferguson, Marilyn. The Aquarian Conspiracy: Personal and Social Transformation in our Time. New York: Putnam’s New York, 1980. Print.

Frank, Thomas. The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1997. Print.

Frank, Thomas. “The Big Con” The Guardian. Jan 6th (2001). Print.

Lasch, Christopher. The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1979. Print.

Ryan, Michael and Douglas Kellner. The Politics and Ideology of Contemporary Hollywood Film. Bloomington, IA: Indiana University Press, 1988.

Wood, Robin. Hollywood From Vietnam to Reagan. New York: Columbia University Press, 1986. Print.

Written by Toby Nuttall, London Metropolitan University (2001); edited by Guy Westwell (2011), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2011 Toby Nuttall/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post