Plot Berlin, present day. Jan and Peter are anti-capitalist activists who call themselves ‘the edukators’. Their protest involves breaking into wealthy households, rearranging the furniture and leaving a note warning “Your days of plenty are numbered”. Activist Jule, Peter’s girlfriend, is a waitress working off the cost of a Mercedes after a car accident with the wealthy Hardenberg. Evicted from her flat, she moves in with Jan and Peter. Whilst Peter is away she develops feelings for Jan and he tells her about the edukators. In the heat of the moment they break into Hardenberg’s house, sharing a moment of passion. Returning the next day to retrieve Jules mobile phone, they are caught by Hardenberg who recognizes her. After involving Peter, the three decide to kidnap Hardenberg. In the Austrian Alps they discover that he was involved in the 1960s student protest movement. Peter learns that Jan and Jule are in love and the trio temporarily disband before deciding to take Hardenberg home as he promises to clear Jule’s debt. The film ends as riot police storm their old apartment only to find a note on the wall bearing the message “Some people never change”. In the version released in Germany, an additional sequence shows the activists aboard Hardenberg’s boat, intent on destroying western European television signal towers on a Mediterranean island.

Film note The Edukators can be situated within a cycle of “Ost– and Westalgie” films produced at the beginning of the new millennium. As the terms suggest, these films explore the nostalgia for pre-1989 East and West Germany prevalent in contemporary German society. Where Ostalgie films such as Goodbye Lenin! (2003) show characters who picture the GDR as a country of community and fairness, Westalgie film The Edukators shows young political activists who are inspired by the 1968 student protests, a movement lead by the SDS (Socialist German Student Union) that consequently conducted left-wing terrorism in the 1970s. In a bid to move beyond legacies left by older generations, the film shows the characters negotiating feelings of guilt and perpetration during a journey into the Austrian Alps.

No place to go The functions of characters in The Edukators are continuously in flux. Despite an initial alignment with Jan, Jule and Peter (the ‘edukators’ of the title) the question as to whether they should be seen by the viewer as perpetrators of their own brand of terrorism or instead as victims of a society in which they feel outcast and powerless, is never answered. Similarly, the spectator is offered numerous opportunities to alter their judgement of Hardenberg. The viewer’s point of view is closely aligned with that of the edukators during the film’s first part, in which “the exuberant side of their protest actions” is highlighted (Cook 325). In a sequence emphasising their light-hearted attitudes, Jan and Jule are shown repainting her apartment so that her deposit will be returned. The accompanying upbeat, non-diegetic music pauses momentarily with a freeze frame of Jule throwing paint at the wall. She says, “You know what? Fuck the deposit!”, following which the music resumes and the picture reanimates. These stylistic choices echo those of a music video in their exaggeration and glamorisation of carefree acts. Furthermore, when Jan paints “every heart is a revolutionary cell” on a wall, Jule poses in front of it and mimics photographs that have become icons of revolution, thus suggesting a process of self-mythologization. The viewer experiences an accentuation of this exuberant behaviour again after Jan and Jule have broken in to Hardenberg’s house: rather than focusing on their political intentions the film shows them swimming in an indoor swimming pool to a soundtrack of rock music. Such treatment presents their insouciant actions and youthful protest as generally positive and thus encourages spectator identification.

During the second section the film begins to manipulate this viewer positioning, demonstrating how “guilt and perpetration can shift back and forth between two generations” (Palfreyman 2010: 148). Throughout the film “an ambiguous conflation of victimhood and perpetration, guilt and suffering is centred on the debt owed by […] Jule to the bourgeois Hardenberg” (Palfreyman 2010: 159). Initially Jule is presented to the viewer as a helpless victim, her enemy a faceless representation of capitalist values and her punishment unbefitting for her crime. However, when presented with the opportunity to break into Hardenberg’s house, she is transformed from victim to perpetrator, her motivation a desire for revenge rather than principled protest. When Jule asks Jan about the edukators, he states that his reasons for ‘edukating’ people are to make them feel unsafe and to force them to question their needlessly extravagant lifestyles. His and Peter’s enemy is a system and set of beliefs as opposed to Jule’s less honourable personal vendetta.

Until Hardenberg physically enters the narrative he remains a symbolic figure; a capitalist and the antithesis of the edukators. This is demonstrated when Jan and Jule explore his extravagant house and car collection, and by his thoroughly unjust treatment of Jule. When physically introduced however, he becomes the victim, attacked and restrained in his own home. He is shown standing outside his house, suspecting strangers are inside, and his anxiety and vulnerability work to elicit an empathic response from the audience, despite our previous alliance to Jan and Jule. Consequently, as the second section of the film begins, both Hardenberg and the edukators simultaneously represent victim and perpetrator. Further complicating the guilt-perpetration dynamic, it is revealed that Hardenberg was once a leader of the SDS, thus disrupting his status as a symbolic embodiment of capitalism. Although initially sceptical, the edukators begin to identify with him, as they realise that he once shared their values. They begin to see his subsequent change as a product of his maturity and are perhaps even slightly jealous: his generation was much more politically engaged, believing they had power to effect change, whereas their own lacks involvement due to feelings of powerlessness.

Informed of his past political involvement and aware of his current status, Hardenberg now represents a conflict between lifestyle and beliefs. Actively involved in the 1968 student protest movement, Hardenberg compromised his beliefs to embrace capitalism. A personified contradiction, he is comparable to Hanna Flanders, the “communist draped in Dior” in Die Unberührbare/No Place to Go (2000) (Collinson). Hanna, a communist writer crestfallen by the fall of the Berlin wall, feels as though she doesn’t belong anywhere. Hypocritically she mourns the loss of the GDR, though she never lived there and celebrates communism, yet surrounds herself with decadence. Both Hardenberg and Hanna are forced to confront their contradictions through physical displacement. Hardenberg, when held captive in the Austrian countryside, is forced to come face-to-face with youths who hate him for what he has become, yet respect him for who he was. When wandering drunk and alone Hanna is taken in by a family of former GDR citizens who are celebrating reunification; although these people lived with the reality of communism and not just the idealised version she felt she understood, she still finds their jubilation difficult. In both situations the contradictory characters are prompted to re-examine their beliefs by younger generations. Depending on how the viewer interprets the ending of each film, it can be suggested that the period of return and reflection revives Hardenberg’s old beliefs in The Edukators, whereas Hanna’s experiences in No Place to Go lead to her fleeing in denial.

The weight of the past A trend and desire for nostalgia are clearly detectable in post-unification German cinema. After the popularity of what came to be known as the “cinema of consensus” (Rentschler 249)–a commercial cinema designed to encourage consumption not contemplation–“filmmakers of the late 1990s and the new millennium […] return[ed] to the issue of left-wing terrorism” along with other weighty historical topics (Palfreyman 2006: 12). The Edukators and Christian Petzold’s Die innere Sicherheit/The State I Am In (2000) both use nostalgia to engage with the theme of terrorism, albeit approaching the subject in different ways. The emblems of the somewhat darker past in Petzold’s film are Clara and Hans, who like Hardenberg protested in the late 1960s and 1970s. They fled Germany because of crimes they committed as partisans and now live as fugitives with their daughter, Jeanne. Comparing portrayals of Clara and Hans on the one hand and Hardenberg on the other illustrates the way in which contemporary German society reflects on the experiences of former political activists. Hardenberg was presumably less radical and has been able to integrate himself into the system, echoing those former members of the protest movement who took posts in German government. When speaking of his youth he looks back fondly, presenting an idealistic view of the era, whilst expressing compassion for the edukator’s beliefs. This fondness however, is expressed from a position of financial and personal security, neither of which Clara and Hans possess, and by contrast they do not speak about the past or their beliefs and are “entirely cut off from the Germany they once rejected” (Palfreyman 2006: 20). The details of their crime are never made explicit, but rather are left for the viewer to infer, creating an ominous undertone throughout The State I Am In.

Palfreyman proposes that these “post-cinema of consensus” films attempt to “stake a claim relating not just to the past, but to the present and to the future as well.” (2006: 12). Both films are set in the present day and neither utilise flashbacks, yet “assert power over historical meaning” by indicating how the events of the past shape the experiences and decisions made by those in the present (Palfreyman 2006: 12). Both Jeanne and the edukators are members of a generation often referred to as post-ideological and apathetic. When Clara and Hans die there is no indication that Jeanne intends to continue their legacy; their death, however tragic, frees her from the burden of the past. She clutches at any chance to integrate with her own generation, from which the values of her parents have isolated her. Her desire to belong even overrides her moral sense of right and wrong, exemplified by the theft of a fashionable t-shirt identical to one worn by the first German teenage girl with whom she interacts. In showing Jeanne’s reaction to a screening of Nuit et Brouillard/Night and Fog (1955), The State I Am In manages to draw a direct comparison between the post-ideological generation and the youths of 1968. Despite seeming harrowed by what she has witnessed, the film does not prompt Jeanne to take action, whereas the same film serves as the catalyst for revolutionary action in Die bleierne Zeit/The German Sisters (1981). In marked contrast, in The Edukators, Jan, Jule and Peter do not show such traits; in the city they appear detached but their lack of social inclusion stems from their political beliefs; and, far from being disheartened by sell-out Hardenberg their political opinions never waver. Their certainty in the face of the atrophying of political commitment in the contemporary period might be said to demonstrating the concept of postmemory, defined by Hirsch as being “distinguishable from memory by generational distance and from history by deep personal connection” (22). Even though they have not direct experience of the political activism of the late 1960s, they associate with and justify their actions through a powerful second-hand memory of a period when productive political action seemed possible.

As well as reflecting on West German terrorism, the second half of The Edukators also alludes to the Heimat tradition. The film paints the characters as a broken family, with rural traditional life the cure. The sense of family life associated with Heimat is created by the mise-en-scène. When sitting around the kitchen table in the cabin the edukators are like siblings attempting to settle a family conflict. The interior décor–wooden walls, chequered curtains, and so on–represents the epitome of pure rural family life. The disruption, as is often the case within a family dynamic, is caused by a generational tension, here specifically cyclic, “emerging from the issue of guilt about the war” (Palfreyman 2010: 159); Hardenberg, when politically active, was motivated by a guilt inherited from his parents, whilst the edukators are motivated by their own memories of Hardenberg’s struggle in the late 1960s. The shift from the city, which constantly reminds the characters of their struggles, to the countryside, where their relationships seem to progress and develop through conversation and expression, illustrates the “healing power of rural Heimat for real and symbolic broken families” (Palfreyman 2010: 154). For example, whilst Jan and Jule are away Hardenberg tries to flee, challenging the viewer’s growing sympathy for him; yet after a panicked chase Peter finds him contemplating the beauty of the landscape, as if it had directly intervened to prevent his escape. He tells Peter of how he desired to leave urban life and describes his money as a prison. Disconnected from the realities of the city, Hardenberg’s mood here invites the audience to believe in the reparative effect the rural environment has upon this makeshift family unit.

In an alternative reading, the Heimat location, rather than acting as a tool of reparation, becomes a mask with which to hide unpleasant truths: that the group is irreparable and that Hardenberg is an untrustworthy sell out. It is he who brings Jan and Jule’s relationship to Peter’s attention, causing cracks to appear in the formerly unbreakable group. Moreover, his sly intervention highlights the volatility of young activists. Here The Edukators echoes Der Baader Meinhof Komplex/The Baader Meinhof Complex (2008), which also shows a tension ignited amongst volatile youths (Baader, Meinhof, Ennslin and Raspe) when they live in close proximity to one another. Previously united by their beliefs they quickly turn against each other once imprisoned. Both films show young activists in a certain negative light; their volatility distracts from their cause and in a sense undermines their message.

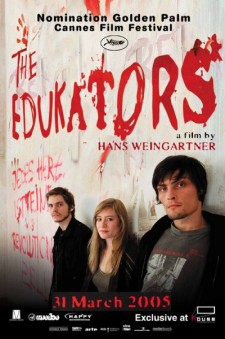

Contemporary Anxiety and the German Road Movie In its portrayal of youth in the new millennium the film touches on some anxieties that seem to permeate modern German society. It is “book ended by scenes of police in full combat gear”, police who firstly prevent the group from protesting and eventually storm their apartment (Palfreyman 2010: 159). These scenes not only activate anxieties prompted by a history of German authoritarian control, from the SS to the Stasi, but also illuminate present day paranoia induced by anti-terror laws. The handheld, documentary style of shooting emphasises the brutal and frenzied nature of these encounters. The director of The Edukators Hans Weingartner also explores this issue in his short film Gefährder/Offender (2009), in which an innocent activist and family man is arrested and confronted with extensive evidence that he has long been under surveillance. On his inspiration for the film, Weingartner said, “You see how dangerous these anti-terror laws are. Now there is a law that the government can observe people and start criminal prosecution without a judge or state attorney” (Badt). Scenes appearing to use surveillance footage are found in both films. The Edukators also acknowledges a resistance to the social injustice of global capitalism. In the opening scenes youths enter a store to protest peacefully against sweatshops, but are quickly forcibly removed. The negative portrayal of major corporations is another theme that runs through contemporary German cinema. In Tom Tykwer’s film Feierlich Reist/Feierlich Travels (2009) the uniformity and monotony of everyday life under globalisation causes the apparent mental breakdown of an international businessman, who is repeatedly bombarded with global brands.

These anxieties are drawn upon during the ending(s) of The Edukators, which directly addresses the viewer’s awareness of global injustice. Indeed, there are two endings, which each lend themselves to slightly different interpretations. The shorter version screened at Cannes and released internationally ends with a police raid of the edukators’ apartment. Here they find a note which reads: “Some people never change”. The longer version, which was released in Germany, depicts the edukators on Hardenberg’s boat. Both endings can be read positively: Hardenberg wrote the note referring to his old self and alerted the edukators so they could leave before the raid. In the extended version he lends them his boat to aid their next mission. Similarly, both can be read negatively; the edukators predict that Hardenberg will report them, writing the note about him and in the longer version also stealing his boat. To interpret the film pessimistically one would understand Hardenberg’s deception to be foreshadowed, either in a hopeless confession that things cannot change or in his agreement with the capitalist figure that things should not be changed. The optimistic viewer would see the note as a defiant statement by Hardenberg or by the edukators in reference to their own commitment. The ambiguity challenges the perspective of the viewer on their own society. In asking them to interpret the ending, it requests that they either acknowledge a global injustice at the root of capitalism or ignore it.

It is difficult to assign one genre to The Edukators. In its first section there are elements of a heist movie or thriller, whilst the love triangle that later develops between Jan, Jule and Peter is reminiscent of a romantic drama. The film also borrows sentiments and iconography from a great American cinematic tradition: the road movie. Steven Cohan and Ina Rae Hark write that “[t]he ongoing popularity of the road for motion picture audiences in the United States owes much to its obvious potential for romanticizing alienation as well as for problematizing the uniform identity of the nation’s culture” (1). Although this statement is applied to American cinema, there is clear justification in claiming the same for German variations on the genre, such as The Edukators. The alienation of the edukators from society takes them on a journey to a beautiful, dreamlike landscape, romanticising their decision to reject the national identity and normal political stance of their generation. It is this journey that, like the allusion to Heimat, allows generational tensions to be explored and worked through. The mode of transport is important to this journey. Not only does the van in the film provide the location for some of the most integral parts of the narrative (the working through of tensions in the group, for example), it also alludes to the origins of the genre–the 1960s counter-culture–simply by being an iconic VW camper-van.

In contrast to the US road movie, in German versions of the genre “departure is portrayed […] less as a conscious rebellion than as the involuntary result of the ubiquitous displacements of unification” (Mittman 329). The edukators, unlike their US equivalents, do not take to the road on a voyage of self-discovery, rather they are prompted to do so by necessity. Similarly, Hanna Flanders is lost on the road with literally No Place to Go, specifically because of her reaction to reunification. Proposing that there is a German road movie genre, No Place to Go, The State I Am In and The Baader Meinhof Complex can be included as they depict journeys of characters disrupted by reunification and end, much like the US road movie, with the characters never being able to return home and dying as a result of their journeys.

The Edukators, despite its weighty themes, is an upbeat, easy film to watch. The mixture of generic conventions presents an accessible narrative and characters that are sympathetic, at times even problematically so. As a result, the viewer is offered insight into the shifting roles of guilt and perpetration across generations, caused by the legacies left throughout the nation’s traumatic past. The film illustrates a nostalgia for the old west, Westalgie, in its portrayal of vibrant and youthful activists willing a political movement similar to that of 1968 and in doing so demonstrates the concept of postmemory. Regardless of whether the viewer sees Jan, Jule and Peter as idealistic youths having a casual fling with political activism or alternatively sees them as inspiring revolutionaries, The Edukators prompts questions concerning global awareness and capitalist control that resonate within contemporary society.

References

Badt, Karin. Germans Think About Germany: “Deutschland 09” Premieres at the Berlinale. Huffingtonpost.com, 24 Feb. 2009. Web. 7 Jan. 2010.

Cohan, Steven and Ina Rae Hark, ‘Introduction’. The Road Movie Book. Ed. Steven Cohan and Ina Rae Hark. London: Routledge, 1997: 1-15. Print.

Collinson, Gavin. No Place to Go (Die Unberührbare). BBC.co.uk, Dec. 2009. Web. 28 Dec. 2010.

Cook, Roger F. “Die fetten Jahre sind vorbei, Edukating the Post-Left Generation”. The Collapse of the Conventional: German Film and Its Politics at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century. Eds. Jaimey Fisher & Brad Prager. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2010. 309-332. Print.

Hirsch, Marianne. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1997. Print.

Mittman, Elizabeth. “Fantasizing Integration and Escape in the Post-Unification Road Movie”. Light Motives: German Popular Film in Perspective. Ed. Margaret McCarthy. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2003. Print.

Palfreyman, Rachel. “The fourth generation: legacies of violence as quest for identity in post-unification terrorism films”. German Cinema Since Unification. Ed. D Clarke. London: Continuum, 2006. 11-42. Print.

—. “Links and Chains: Trauma between the Generations in the Heimat Mode”. Screening War Perspectives on German Suffering. Eds. Paul Cooke & Marc Silberman. New York: Camden House, 2010. 145-164. Print.

Rentschler, Eric. “From New German Cinema to the Post-Wall Cinema of Consensus”. Cinema and Nation. Eds. Mette Hjort & Scott Mackenzie. London: Routledge, 2000. 245-261. Print.

Written by Hannah Farr (2011); edited by Amy Lewis (2012), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2011 Hannah Farr/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post