Plot 1963, Wyoming: Two young men, Ennis Del Mar and Jack Twist, are hired to herd sheep for the summer on Brokeback Mountain. One cold night Ennis joins Jack in his tent, and they have sex. Ennis and Jack continue their sexual relationship until the end of the season. After going their separate ways, Ennis marries Alma and they raise two daughters in Wyoming. In Texas, Jack marries Lureen and has a son. Four years after their first meeting Ennis and Jack are reunited. Alma glimpses the two men kissing. Over the next twenty years, during which Alma divorces Ennis and marries her old boss, Monroe, the men continue to meet, though Ennis maintains they can never be together. When a postcard to Jack is returned to him stamped ‘deceased’, Ennis calls Lureen who tells him that Jack was killed in an accident. In fact, he died as the result of a homophobic attack. Ennis visits Jack’s parents, offering to scatter his ashes on Brokeback Mountain, but Jack’s father refuses (Gilbey).

Film note One of Annie Proulx’s greatest concerns upon hearing that her work was to be adapted was that the essence of her story wouldn’t survive the production process. Due to its homosexual content, developing the story of Brokeback Mountain was never going to be a simple task, and the difficulty of adapting it for the screen was compounded by the unbreakable bonds that Proulx had established in her writing between the iconography of the American western landscape and the story’s historical setting. Brokeback Mountain is principally set in the harsh but sweeping beauty of Wyoming between 1963 and the early 1980s and it is not only the location that Proulx believed to be crucial to the narrative, but this historical period as well. Proulx’s concerns proved unfounded and the process of adaptation was handled with great care and tact to produce a queer cinema classic that was surprisingly successful at the box office.

Wyoming, widescreen and the written word Proulx’s short story was first published in The New Yorker on 13 October, 1997. Within three months of Larry McMurty and screenwriting partner Diana Ossana reading it, a completed script was sent for Proulx’s approval. McMurty believes one of the reasons why great literature is so rarely adapted into equally great film is that of literary style; so often inseparable from subject matter. McMurty notes that “[s]tyle and substance fuse so intricately that most directors will be hard put to find even an approximate cinematic equivalent to a literary style” (139). Working with Proulx’s sparse prose and the minimal dialogue of the story’s taciturn characters, McMurty and Ossana’s screenplay hones in on site-specific action and episodic verbal exchanges. Extending the thirty-five page story into a feature film gave the screenwriters the opportunity to further contextualise the principal characters. The script shows how Jack and Ennis “drift into their traditionally masculine jobs much as they drift into their marriages to Lureen and Alma: not so much out of desire or love for their spouses, but because it is what is expected of them” (Benshoff & Griffin 2009, 407). The affording of time to the secondary characters, Ennis’ economic struggle and the pressures of an intolerant society, emphasise the impossibility of Jack and Ennis’ relationship and help contextualise their love affair in the difficult cultural climate of the 1970s and early 1980s. The script also allows the film to develop at a suitable pace which offers the director and actors the discretion to use camerawork, facial expression and body positioning to convey meaning in keeping with Proulx’s literary style. In Proulx’s story, the states of Wyoming and Texas are almost central characters on par with Ennis and Jack. To try to capture this, Rodrigo Prieto’s cinematography lingers on the wide-open space of the mountain, contrasting this with claustrophobic small town architecture and the busy, temperamental space of the Texas rodeo. Ang Lee utilises long, static shots combined with tracking shots, which variously attempt to convey how their love affair is shaped by the solitude, privacy, and freedom the mountain offers.

The reality of the western American rural landscape, and the social and economic changes within it, is a recurring theme in the work of Proulx. In Brokeback Mountain she carefully charts the failing farming communities and a disappearing lifestyle, claiming to be: “something of a geographic determinist, believing that regional landscapes, climate and topography dictate local cultural traditions and kinds of work, and thereby the events on which [her] stories are built” (McMurty, Proulx, Ossana 2006, 129). For Proulx, Wyoming is one of America’s store cupboards that has been stripped of its resources. The aspirations of many of the inhabitants of these lapsed Christian communities often lie with the chance of escape through the unrealistic ambition of making it big on the rodeo circuit or advancement by marrying into a more secure lifestyle. Jack marries Lureen, a Texan farm machine merchant’s daughter after an unsuccessful attempt at making it big on the rodeo circuit: “Made three thousand dollars that year, almost starved.” Alma divorces Ennis and marries Munroe, the local store-owner; the land no longer able to support its inhabitants and their livestock. Ennis is the personification of the difficulties of rural life: by his own admission he states that “all the travellin’ I ever done is goin around a coffeepot lookin’ for the handle,” a statement that might be read as both a description of his material circumstance and a fatalistic acceptance of a world in which opportunity is severely limited.

If the written word is the medium of telling and film is the medium of showing, the screenplay is a hybrid of the two. Transposing Proulx’s words to the screen demonstrates the collaborative act of movie-making. In the film, we see Jack and Ennis’ scuffle atop Brokeback, which leads to Ennis’ bloody nose and bloodstained shirt that “goes missing”. This incidental set-up makes for the film’s final emotional pay-off, as in the closing scenes, we see Ennis discover Jack’s cherished memento. In Proulx’s story however, this information is revealed as the shirt is discovered. The film builds chronologically to an emotional climax in which Ennis’ understanding of his love for Jack tragically comes only as a result of his death. Proulx and Lee disagreed over the Motel Siesta scene. In the book it is here that Jack and Ennis talk most candidly and at length regarding their feelings: “If you can’t fix it you got a stand it.” Lee however, condensed the scene, focusing on both sexual catharsis and a reinforcement of their commitment to one another. In the film, Ennis’ denouncement of a future together comes once they have retreated to Brokeback Mountain. It was this disagreement that made Proulx realise that the story was no longer her story, but Lee’s film, in which words on the page are traded for incidental glances, beautifully photographed natural landscapes, and the mise-en-scene of unspoken and thwarted desire.

The greatest unproduce-able screenplay ever written In its quest for funding, Brokeback Mountain garnered industry notoriety as one of the greatest unproduce-able screenplays ever written” (Benshoff 203). Various potential producers (Scott Rudin) and directors (Gus Van Sant) came and went, but major Hollywood studios were not willing to take risks with subject matter that “queer[ed] traditional concepts of American masculinity and the film genre most closely tied to it representation, the Western” (Benshoff & Griffin 2009, 406). In 2004, Focus Features co-president James Schamus green-lit the project having shown initial interest at Good Machine some years earlier. Schamus insists films don’t have to reach mass audiences and believes that Focus Features “is a place where voices from outside the mainstream speak, but they’re speaking face-forward to the rest of the culture”. Schamus signed Lee, with whom he had an established working relationship, but whose commitment to Hulk (2003) had forced him to decline Schamus’ initial offer. The project gained momentum and River Road Entertainment were brought in to co-produce. Initially the film was to be shot largely in Wyoming, but with no filmmaking tax breaks on offer in the US, shooting was relocated to Canada, in and around Calgary. To handle the local financial and logistic element, Alberta Film Entertainment joined the production team. The film was produced on a small budget of $14m, with a $5m spend on marketing.

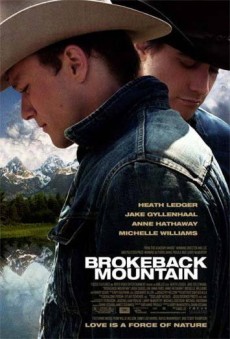

Brokeback Mountain quickly became known as “the Gay Cowboy Movie”, an epithet Proulx objected to, preferring to think of her story as one about “‘destructive rural homophobia,’ not gay cowboys” (Benshoff 203). With its tagline “Love is a Force of Nature”, the film, despite its western setting and iconography, was promoted as a love story. Schamus took inspiration for the film’s marketing poster from James Cameron’s story of a tragic love affair, Titanic (1997), unifying Jack and Ennis’ bodies in a denim embrace, but also separating them with opposing postures and glances. A well-known director, rising Hollywood stars and controversial, hard-to-sell content sparked intense media interest, against which Lee’s strategy was to downplay the homosexual nature of the film in favour of promoting it as a universal tragic love story. Schamus asserted: “We never pitched or marketed the controversy. We unequivocally kept the film front and centre and audiences responded to it as a movie” (“Biography for James Schamus”).

Although the producers attempted to attract a wide audience, Whitney Dilly notes that Schamus’s marketing strategies were inevitably skewed “to reach sympathetic viewers, particularly women and gays” (162), with many commentators predicting only a moderate success despite the film winning the Golden Lion at the 2005 Venice Film Festival. Indeed, the film opened on 9 December 2005, showing at only five cinemas across New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco; cities recognised for their metro-sexual cultures and large gay communities. This limited release grossed $547,425 in its opening weekend and the film achieved “the highest per theatre average [$109,485] on record for a live action movie” (Gray). Focus Features’ president of distribution Jack Foley reported a “good representation of males as well as females, and people from 35 years old to seniors. Foley added that women [would] be the key to the picture’s future success” (Gray). A carefully executed gradual roll-out combined with good word-of-mouth and critical praise as the awards season loomed led to an expansion to 2,089 cinemas and an eventual domestic gross of $83m – the highest grossing film to depict graphic scenes of male homosexual sex by some margin.

Critical reception of the film was diverse, and often divided. Re-elected in 2004, President George W. Bush’s election campaign had specifically targeted the notion of family values, including tighter restrictions on abortion and the banning of same-sex marriages. However, contrary to the president’s anti-gay stance, several states had legalised same-sex civil partnerships and a 2005 federal court decision (Citizens for Equal Protection v. Bruning) ruled that prohibiting the recognition of same-sex relationships violated the Constitution. In this context, the “influential Conference of Catholic Bishops gave [Brokeback Mountain] an ‘O’ rating, classifying it as morally ‘offensive’” (Dilly, 162). Steven D. Greydanus, author for the website ‘Decent Film Guide – Film Appreciation and Criticism Informed by the Christian Faith’, despite valuing the film’s artistic/entertainment value, was unable to recommend it to his readers due to its lack of moral/spiritual values. For Greydanus, the combination of Ennis’ religious un-education, Jack’s religious mis-education and his mother’s spiritual ambiguity results in a film that is “more concerned with telling a story about characters than with making sure that the viewer feels a certain way about a moral issue.” He deems Jack and Ennis’ relationship, and the film as a whole, as “an indictment not just of heterosexism but of masculinity itself, and thereby of human nature as male and female. It’s a jaundiced portrait of maleness in crisis” (Greydanus). In contrast to criticism by religious conservatives, the liberal-left newspaper, the New York Daily News called the film “a perfectly adapted screenplay […] from Annie Proulx’s flawless New Yorker short story […] a film that […] will take its place among the classics of Hollywood love stories” (Matthews). Sean Macaulay noted that “kissing cowboys […] should offer the perfect balance now that Hurricane Katrina has turned the tide against Bush, creating a frisson in the more conservative states and wholeheartedly liberal approval in Hollywood” (Macaulay). With critical opinion divided the success of the film with audiences might be read as indexing a groundswell of left-liberal opinion in the mid 2000s, something confirmed by the nominations for Best Picture at the 2006 Academy Awards, which were dominated by independent films displaying left-liberal sentiments, including Crash (2005), Capote (2005), Good Night and Good Luck (2005) and Brokeback Mountain (2005), and culminating in the election of Barack Obama in 2008.

A New ‘New Queer Cinema’ Benshoff and Griffin argue that Brokeback Mountain is “possibly one of the most important American films of recent years […] never before had such a widely released American film represented a decades-long love affair between two men, let alone had them played by handsome Hollywood heart-throbs like Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal” (406). Reaching a point where this is possible has involved considerable struggle. Shifts in tolerance and acceptance of homosexuality can be traced to the 1969 Stonewall riots and the subsequent rise of the Gay Liberation Front and other gay activist groups, who joined feminist and black advocates in demanding their civil rights. Underground art cinema of the mid 1960s such Blow Job (1963), My Hustler (1965) and Lonesome Cowboys (1968) “drew from the gay underground culture and openly explored the complexity of sexuality and desires” but these were confined largely to gay audiences (Davies 49). In 1970, Midnight Cowboy (1969), a story about a hustler in New York who resorts to gay prostitution in order to survive, won the Academy Award for Best Film. However, the film received an ‘X’ rating for its content and caused a public backlash. Awareness of gay culture and discrimination continued to be raised in the 1970s (particularly with the removal of homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association’s list of mental disorders in 1974), and cinematic visibility of gay characters and themes increased through the 1970s.

In the 1980s Hollywood mirrored Reagan’s moral majority conservatism “by releasing a series of queer psycho-killer horror movies: Dressed to Kill (1980), Deadly Blessing (1981), Windows (1980), The Fan (1981) and perhaps most (in)famously Cruising (1980)” (Benshoff & Griffin 2009, 334). While some films did attempt positive homosexual portrayals (Can’t Stop The Music, 1980; Making Love, 1982) they were met with either criticism and/or poor box office returns. Against this backdrop, Ruby B. Rich considers 1992 “a watershed year for independent gay and lesbian film and video” (53); with a new wave of gay filmmakers emerging (Benshoff & Griffin 2004, 53). Around this time scholars were successful in criticising the binary paradigm of “‘gay or straight’”, insisting that hybrid (bisexual, transgender) sexual identities be considered. These trends and the wider prominence of identity politics allowed a diverse body of “irreverent, energetic, alternately minimalist and excessive” films to challenge heteronormative filmmaking (Benshoff and Griffin 2004, 54). Notable examples of this ‘New Queer Cinema’ movement include Paris is Burning (1990), My Own Private Idaho (1992) and Swoon (1991). Philadelphia (1993) was hailed as a groundbreaking mainstream crossover informed by the wider movement; the film shows lawyer Andrew Beckett (Tom Hanks) getting fired by his firm when they discover he is suffering from AIDS. He hires a homophobic, black, “‘bottom-of-the-barrel’” lawyer (Denzel Washington) to fight his case. Whilst the casting of Hanks, Washington and Antonio Banderas (as Beckett’s lover Miguel) opened the film up to diverse mainstream audiences, the intimacy and all round “‘gay-ness’” of the homosexual relationship is all but eradicated in favour of the bureaucratic interaction between racism and homophobia, in which Beckett’s AIDS becomes the most prominent feature of his sexuality. Miguel’s foreignness ostracises him from an all-American milieu (perfectly represented by Hanks’ casting), and the depiction of a near-perfect heterosexual family support system offers some relief for conservative audiences. However, Hanks’ Academy Award for Best Actor represents a willingness within the mainstream to tackle to topic of AIDS compassionately.

One of the legacies of Brokeback Mountain is that of an industrial and critical shift in attitude towards queer film and queer filmmakers. The film’s direct address of homosexual intimacy and its complication of homosexual and heterosexual desire blurs the lines between that of a gay and straight. Subsequent bio-drama Milk (2008) and comedic melodrama The Kids Are All Right (2010) have followed suit; the former in its portrayal of Senator Harvey Milk’s political ascendency; the latter in its depiction of a lesbian couple facing the trials and tribulations of co-chairing the nuclear family, coupled with the on-set of middle age and marital strife. Significantly, what these films represent is not only a move away from the deliberately antagonistic films of the New Queer Cinema canon, but an explicit branching out of gay cinematic portrayals in the Hollywood mainstream in terms of both character and genre, and a confidence in and respect of subject matter. Studios seem more willing to green-light projects that seriously engage with a wider gay discourse, despite an apparent glass-ceiling on box-office revenue. Similarly, where once queer roles were considered harmful for one’s reputation, reputable actors are now seem to relish the opportunity to increase their range. This critical rethinking is no better exemplified than by the Academy’s recognition of such films in terms of writing, directing, acting and overall cinematography.

Brokeback Mountain is a powerful story that trades on the love-as-tragedy archetype. The film has left some (gay?) viewers questioning where it stands in relation to, say, gay civil rights. Some may interpret Jack’s demise as a consequence of his falling victim to an insatiable libido, and Ennis’ solitary existence deriving from his inability to deal with his homosexual inclinations. However, the film, like Proulx’s story, stays true to its geographical and historical setting (as were the author’s wishes), as opposed to re-appropriating itself as a ‘coming-out’ tale for the modern generation. Narratively speaking, the film serves as a cross-section of gay life in the rural mid-west in the latter half of the twentieth century, and offers a platform for contemporary analysis of the recent past and future direction of the civil rights movement, while simultaneously depicting an experience of homosexuality and homophobia by a gay community that has been traditionally overlooked. The film’s financial success and mainstream cross over, whether it be hinged upon the aforementioned ‘heart-throb’ casting, or the film’s critical success, has paved the way for a refreshed, integrated interpretation of gay cinematic content, destabilising “patriarchal heteronormativity [and] queerly teasing out the interrelated connections between homosexuality, heterosexuality and male homosociality” (Benshoff & Griffin 2009, 407).

References

Aaron, Michele. New Queer Cinema: A Critical Reader. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004. Print.

Benshoff, Harry and Griffin, Sean. Ed. Queer Cinema: The Film Reader Abingdon: Routledge, 2004. Print.

Benshoff, Harry and Griffin, Sean. America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality at the Movies. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Print.

Benshoff, Harry. “(Broke)back to the Mainstream: Queer Theory in Queer Cinema Today.” Film Theory and Contemporary Hollywood Movies. Ed. Warren Buckland. London & New York: Routledge, 2009. 192-212. Print.

Davies, Steven Paul. Out at the Movies: A History of Gay Cinema. Harpenden: Kamera Books, 2008. Print.

Dilly, Whitney Crothers. The Cinema of Ang Lee: The Other Side of the Screen. London: Wallflower Press, 2007. Print.

Gilbey, Ryan. “Review: Brokeback Mountain”. Sight and Sound. Jan (2006): 50. Print.

Gray, Brandon. “‘Brokeback Mountain’ Rides High in Limited Release.” boxofficemojo.com. Box Office Mojo, 12 December 2005. Web. 20 Feb 2012.

Greydanus, Steven. D. “Review: Brokeback Mountain.” Decent Film Guide: Film Appreciation and Criticism Informed by the Christian Faith. decentfilms.com. Decent Film Guide, n.d. Web. 20 Feb 2012.

Macaulay, Sean. “LA Story.” thesundaytimes.co.uk. The Sunday Times, 15 December 2005. Web. 26 Feb 2012.

Matthews, Jack. “Popcorn Flicks Were More Filling.” NYDailyNews.com, New York Daily News, 19 December 2005. Web. 25 Feb 2012.

McMurty, Larry, Diana Ossana and Annie Proulx. “Brokeback Mountain: Story to Screenplay”. London: Harper Perennial, 2006. Print.

Proulx, Annie. Brokeback Mountain in Close Range: Brokeback Mountain and Other Short Stories. Harper Perennial: London, New York, Toronto and Sydney, 1999. Print.

Rich, Ruby B. “The New Queer Cinema”. Queer Cinema: The Film Reader. Eds. H. Benshoff and S. Griffin. Abingdon: Routledge, 20004. 53-59. Print.

Testa, Matthew. “Exclusive PJH Interview: At Close Range with Annie Proulx.” planetjh.com. JH Weekly, 7 December 2005. Web. 20 Feb 2012.

Written by Andy White (2010); edited by Daniel Robson (2012), Queen Mary, University of London.

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2012 Andy White/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post