Plot Der Räuber tells the story of successful Viennese marathon runner and serial bank robber, Johann Rettenberger. Opening with Rettenberger in prison convicted of armed robbery, we follow him from his release. For a while he lives a quiet life with his girlfriend Erika. However, his addiction to the passion, the kick, the exercise and the symmetry of the perfect robbery propels him to take off for a regular fix–as much as three times a day. With each robbery he takes higher risks and pushes the limits of his running. His parole officer, concerned that Johann is not cooperating, tries to reason with him after a marathon. Irritated, Johann kills him. Finally he is discovered and arrested by the police with the help of Erika, only to escape shortly after and bolt into the forest. Hunted by the police he ascends a hill, apparently to be trapped at its peak. Yet once again he escapes, runs to the nearest village and steals an old man’s car; during the robbery he is stabbed in the chest. Eventually, after numerous evasions, he stops the car at the side of the road, breathless and coughing blood. His last words are to Erika who he calls and whose voice he listens to as he dies.

Film note The films produced by the Berlin School have been described as “[r]ecalcitrant and stern” and “slow and dreary” (Oskar Röhler in Abel), “hiding behind form” (Abel), “apolitical” (Doris Dörrie in Abel). But do these comments accurately describe the contemporary German cinema or can the films associated with the Berlin School be considered instead as a form of counter-cinema? A cinematic riposte to both the populist comedy boom of the 1990s and what Eric Rentschler describes as a moribund “cinema of consensus” (262)? This essay will address this question via an examination of Benjamin Heisenberg’s 2009 film Der Räuber/The Robber. A brief history of the Berlin School will provide context and then the film will be analysed first in relation to content, with a focus on the main protagonist, and then in relation to film aesthetics.

Heisenberg and the Berlin School From 2003 a group of German filmmakers and their films were celebrated as sharing a common aesthetic style and approach. “Le nouvelle vague allemande”, or “German new wave”, was the label given by French critics to this cinematic movement, otherwise known as the Berlin School. Key directors of the first generation of this now well-known film movement include Cristian Petzold, Thomas Arslan and Angela Schanalec, all of whom began their studies at the Deutsche Film und Fernsehakademie Berlin in the early 1990s. Here, under the tutelage of Harun Farocki and Harmut Bitomsky, two politicised filmmakers with backgrounds in documentary and the theoretical concept of “anti-narrative”, Petzold, Arslan and Schanalec resisted the prevalent styles of contemporary German filmmaking, which generally followed a conventional narrative structure and focused on historical and political themes. Film such as Wolfgang Peterson’s Das Boot/The Boat (1981), a classic portrayal of heroism in war, Oscar Hirschbieger’s Der Untergang/Downfall (2004), which follows Hitler’s last days in the Führerbunker, and Wolfgang Becker’s comic reunification film Goodbye Lenin! (2004) were commercially successful and explored the fraught terrain of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, or “coming to terms with the past”. However, although their subject matter appeared at first glance to be searching and controversial – and the mainstream press celebrated the films as “ingenious, entrepreneurial endeavors” that marked a renaissance of German film, others criticized the films for simply mimicking Hollywood without “advancing the art of filmmaking” (Abel). The same criticism was also leveled at the formulaic films of the mid-1990s comedy boom, including Der bewegte Mann/The Most Desired Man (1994). As Rentschler puts it, this “cinema of consensus” sought neither to challenge nor to inspire, but evoked merely affirmation from audiences habituated to “a culture of short attention spans and disposable images” (262). In reaction to this “cinema of consensus”, and its resolute focus on the past, the Berlin School filmmakers turned their attention to the “here and now”, especially the experience of everyday life. The filmmakers also adopted a non-commercial film style, or shared aesthetic vision, which included a preference for long takes, the poetic use of diegetic sound, and a painterly precision in framing.

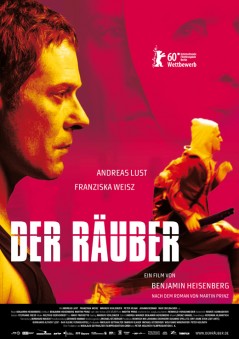

Heisenberg is a key member of the second generation of the Berlin School and his work can be located in this counter-cinematic endeavour. Especially indicative of his involvement with the movement is his joint project with Christoph Hochhäusler, namely Revolver, the film magazine that they founded in 1998 together with Sebastian Kutzli, and of which he is both editor and publisher. Revolver focuses on peripheral filmmaking, taking particular interest in the films of the first generation of Berlin School filmmakers described above. Heisenberg’s own filmmaking career began when he wrote the screenplay for Hochhäusler’s Milchwald/This Very Moment (2003) and directed his first feature Schläfer/Sleeper (2005). This then led to the release of his latest film, Der Räuber/The Robber in 2009, which earned him the Bavarian Film Prize for Best New Director and a nomination for the Golden Bear at the 60th Berlinale.

Rettenberger as cipher Based on real events and a book by Martin Prinz, the opening scene of The Runner shows the main protagonist Johann Rettenberger running. Running is an activity we readily associate with freedom and space but the camera reveals that Rettenberger is in fact a prisoner, restricted by grey walls and wire fences. As the film proceeds we learn that Rettenberger is a successful Austrian marathon runner whose obsession with improving his fitness and pushing himself to his limits has driven him to crime. Rather than material gain, the execution of the crime and running to escape from the police fuels an addiction to adrenaline and the desire to commit the perfect robbery.

Immediately intriguing, Rettenberger is a challenging, morally complex and entirely strange individual character. Abel writes that the films of the Berlin School “image their characters’ lived refusals to either embrace the cliched desires of the individual and social security or pursue the bourgeois demand for social upward mobility”. In this sense, Rettenberger is the perfect example of the Berlin school protagonist: rather than conform to society’s rules he steals money from banks with no apparent regret and is uninterested in all elements of a so-called “normal” life – a relationship, a secure home, a family. In the opening sequence he explains to his probation officer that what he most looks forward to when leaving prison will be to “no longer run in circles”.

Unlike the majority of Berlin School films The Robber takes place in a well-known, affluent European city, as opposed to the ‘transient’, ‘in-between’ spaces used, for example, by Petzold in his “Ghost” trilogy (1999-2007). By choosing Vienna, Heisenberg sets up a contrast between the city and nature, where the city symbolises the state, and nature, freedom. When Rettenberger is forced from the city, hunted like an animal, he flees to nature – and it is nature that temporarily protects him, offering him a place to hide. This trajectory mirrors a transient mindset growing in contemporary Europe, one that disengages with the urban and the state, and which instead yearns to be free of society’s restrictions.

The film is also distinctive in the way it distances the audience from Rettenberger. His emotional coldness and pious sociopathy are peculiar but interesting, and it is curiosity rather than empathy or attraction that shapes spectatorial engagement. Despite his detached, unemotional approach to life, we engage with him as an outsider as we imagine the alienation we may feel if we were to reject contemporary society. With point-of-view shots, and a lingering camera that attempts to penetrate Johanns’s armor-like carapace, not only do we see this alienation, we experience it too, in our attempts to decipher his inner psychological world. As Heisenberg notes “the camera does not let the viewer identify with the characters, but it is not really distancing either […] it positions [us] in in-between space […] holding us suspended in a middle space that’s quite akin to the characters own subject position” (qtd. in Abel).

The alienation from society felt by Rettenberger can also be found in other Berlin School films. As Olaf Möller notes in relation to Yella: “the factory and the city [are] separated by the Mittellandkanal in a zoning of life and work that renders the town a demonstration of the alienation at the heart capitalism.” (42). This alienation resonates in The Robber, as, for example, in the frequent mid-shots of Rettenberger driving, where his serious, detached expression remains unaffected by the light, upbeat diegetic pop music playing from the car radio, thus emphasising the invisible boundary between him and the easy pleasures of consumer society.

What is also striking about Johann is his ostensible emotional numbness and his inability to feel empathy. He tells his probation officer that he has no contact with his family or friends and when the officer asks “do you have anyone to talk to?” Rettenberger does not even appear to understand the question. On occasion, flashes of emotion are shown: desire for Erika during a long embrace; jealousy when she is talking to another man; irritation when he kills his probation officer. But these emotions remain partial and attenuated: Rettenberger does nothing to advance his relationship with Erika, she is simply like the wider society: something that exists that he is forced to interact with.

Emotional distance and apathy are traits displayed by a number of protagonists of other Berlin School films. Köhler’s Bungalow (2002), for example, focuses on the boredom and passivity of Paul, a soldier who is AWOL. Similarly in Petzold’s Gespenster/Ghosts (2005), although the central character Nina is shown to have feelings towards Toni, she never purposefully acts on them. Petzold explores related themes in Yella (2007), where the eponymous central character has the chance to reimagine her future, and yet she rejects the notion that she could change her life and thus reaffirms her impotence. This pessimistic description of emotional muteness by Berlin School filmmakers contrasts with other contemporary German films that present characters burning with emotion, entirely motivated by being true to themselves, as, for example, with Sibel and Cahit in Turkish-German filmmaker Fatih Akin’s Gegen die Wand/Head On (2004) or the light-hearted and idealistic Alex in Wolfgang Becker’s Goodbye Lenin! (2003).

Berlin School films are often criticised for being apolitical and yet the depiction of Rettenberger’s disassociated physical and mental state contains the kernel of a subtle political critique. The central protagonist of Tom Tykwer’s hugely popular and commercially successful Lola Rennt/Run Lola Run (1998), for example, is an icon of a new Germany – a world of techno music, neo-liberal views, bright colours, casinos and possibility. In contrast, Rettenberger runs blind, embodying an even newer Germany, one not so celebratory, less idealistic, driven by his sense that this new system restricts personal freedom and should be rejected.

Film form Moller claims that the Berlin School is “a cinema devoted to the real as well as to realism” (41). The Robber is based on real events and the decision to film the Vienna marathon sequence live during the actual event lends further credence to the film’s realist aesthetic. In the commentary contained on the DVD release of the film Heisenberg stated that he wanted to capture the “energy and atmosphere” of an actual marathon, whilst abstaining from “digital imaging to create crowds and runners”. Producer Michael Kitzberger further explains how cameras were installed at the finish line and it was arranged with organisers that actor Andreas Lust would be treated as a competitor and announced by the commentator as Johann Rettenberger so that the reaction to his victory would, ironically, appear to be authentic.

Heisenberg also places the film within the Berlin School’s realist tradition through specific aesthetic choices and filming methods. Regarding colour and lighting, for example, Heisenberg favours a realist tone over vibrant shades or “mood” lighting. The first of Johann’s and Erika’s intimate scenes is barely visible, seemingly illuminated by moonlight, or perhaps the light from the street. This supports a realistic atmosphere as opposed to constructing a romantic mood. Long shots are a motif of Berlin School filmmaking. A static or slow panning camera will often describe a space and then action will unfold within this space. For example at the dawn start of the ‘Bergmarathon’, the camera sees the space before the runners enter the frame and remains there after they have disappeared. By this method Heisenberg establishes that these spaces exist whether or not the characters inhabit them, thus emphasising their status as ‘real’ places. The static camera also contributes to what Abel refers to as a “tendency to stare”: the long take invites the audience to look, but then to look again, encouraging the viewer to find something extraordinary within the everyday. Theorists such as Andre Bazin and Seigfried Kracauer have claimed that this technique encourages the viewer to perceive the otherwise overlooked or unseen, and that this allows the world to be scrutinised more thoroughly and critically (Tredell 61-100).

Uniquely, and diluting its realist aesthetic somewhat, The Robber also contains chase scenes that are not unlike those produced in Hollywood (albeit on a non-Hollywood budget). During these scenes the camera moves violently, tracking Rettenberger with a Steadicam shot, as if the viewer were running alongside him. When Rettenberg is not running, he is driving a car; tracking or panning shots create movement in scenes where there is no distinct action. When hiding, the camera, recalling Heisenberg’s first film Sleeper, “stalks the criminal with a precision that makes The Shining (1980) look untamed” (Frey). Sharp cuts, pounding music, the ominous approach of the police, POV shots from hiding positions, the sound of heavy breathing: all these techniques create tension as they do in the traditional thriller. More usually associated with the commercial cinema, these techniques fracture some of the formal restraint usually associated with the Berlin School and give the film a mainstream inflection. However, this incessant movement remains dovetailed with the wider thematic concern of a man unable to fit in. Dimitris Matheou notes in relation to Yella, an altogether calmer film, that the central character is defined by “a criss-crossing path that delineates [her] inner stasis”. It is an observation that points to how the frenetic pace of The Robber might be read as an extension of the wider concerns of the Berlin School rather than simply a concession to the multiplex audience.

Wounded during his final flight from the police and unable to run, Rettenberger continues his escape in a series of stolen cars. Trailed by a helicopter and a fleet of police cars, his chances become increasingly slim, but it his injury that forces him to slow the car to a stop. Barely able to breath he phones Erika whose voice he listens to as he dies. Knörer interprets Yella as “a meditation on people caught in and crushed by the capitalist mindset whose options gradually sink to a choice between life and death”. If we apply this interpretation to The Robber, it can be said Rettenberger first chooses life in his attempt to escape but when this fails his accepts, indeed, passively accepts, his death. The viewer is left with an impression of Rettenberger as a curious and affecting character who signifies a dissatisfaction with the modern day world. He is not overtly political; in fact if anything Rettenberger is completely disengaged with society and its politics; but through this disengagement the film suggests that there is a flaw in society; and in this sense The Robber implicitly “deconstruct[s], denounce[s] and deride[s] [the] new right wing conservatism” that characterises modern German society (Möller 43). As such, thematically and aesthetically The Robber successfully repudiates claims that the films of the Berlin School are dull and void of politics.

References

Abel, Marco. “Intensifying Life: The Cinema of the Berlin School”. Cineaste.com. 2008. Web. 03 Sept. 2012.

Baute, Micheal, Knorer, Ekkehard, Pantenburg, Volker, Pethke, Stefan, and Rothhler, Simon. “The Berlin School: A Collage”. Sensesofcinema.com. 11 July 2010. Web. 03 Sept. 2012.

Frey, Mattias. “Art and Artifice: German Films at the 60th Berlin International Film Festival”. Sensesofcinema.com. 11 July 2010. Web. 03 Sept. 2012.

Knörer, Ekkehard. “Luminous Days: Notes on the New German Cinema”. Closeupfilmcentre.com. 2008. Web. 03.09.2012.

Matheou, Dimitris. “Review: Yella”. Sight and Sound. 17.10 (2007), 82. Print.

Möller, Olaf. “Vanishing Point”. Sight and Sound. 17.10 (2007), 40-43. Print.

Eric Rentschler, “From New German Cinema to Postwall Cinema of Consensus,” in Hjort, Mette. ed. Cinema and Nation. London: Routledge, 179-193. Print.

Seibert, Marcus. Revolver: Kino muss gefährlich sein. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag der Autoren, 2006. Print.

Tredell, Nicolas. Cinemas of the Mind: A Critical History of Film Theory. Cambridge: Icon, 2002. Print.

Written by Amy Lewis (2012); edited by Guy Westwell (2012), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2012 Amy Lewis/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post